Assessment of the role of ad hoc governance, peace and security mechanisms in supporting the PSC’s mandate

Date | 5 August 2025

Tomorrow (6 August), the African Union (AU) Peace and Security Council (PSC) will convene its 1294th session to assess the role of ad hoc governance, peace, and security mechanisms in supporting the PSC’s mandate.

The session will commence with opening remarks by Mohamed Khaled, Permanent Representative of Algeria to the AU and Chairperson of the PSC for August 2025, followed by introductory remarks from Bankole Adeoye, AU Commissioner for Political Affairs, Peace and Security (PAPS). Solomon Dersso, Founding Director of Amani Africa Media and Research Services, will also deliver a presentation.

Following the establishment of the PSC and the structures for the implementation of its conflict prevention, management and resolution decisions, the AU has been enterprising in the tools/instruments that it has innovatively designed and implemented for peacemaking and mediation. The most notable of these innovations was the use of ad hoc governance and peace and security mechanisms instituted in support of the mandate of the PSC. As elaborated in The African Union Peace and Security Council Handbook: Guide on the Council’s Procedure, Practice and Traditions, the use of these mechanisms is built on the provisions of the PSC Protocol.

Article 6(c) of the Protocol Relating to the Establishment of the Peace and Security Council of the African Union PSC mandates the Council to engage in ‘peacemaking, including the use of good offices, mediation, conciliation, and enquiry’. To effectively implement these mandates, the Protocol further authorises the PSC to establish subsidiary bodies as needed. In particular, Article 8(5) provides that the PSC may create such bodies, including ad hoc committees, as it deems necessary to undertake specific tasks such as mediation, conciliation, or fact-finding enquiries.

These high-level peacemaking and mediation tools that the AU instituted as instruments for the management and resolution of crisis and conflict consist, mainly, not exclusively, of:

- ad hoc committees for mediation consisting of leaders of a group of states (Art. 8(5) of the PSC Protocol) and

- High-level panels.

These ad hoc governance, peace and security mechanisms are often established by the PSC under the authority vested in it by its Protocol, but they are also at times instituted by the AU’s supreme authority, the AU Assembly.

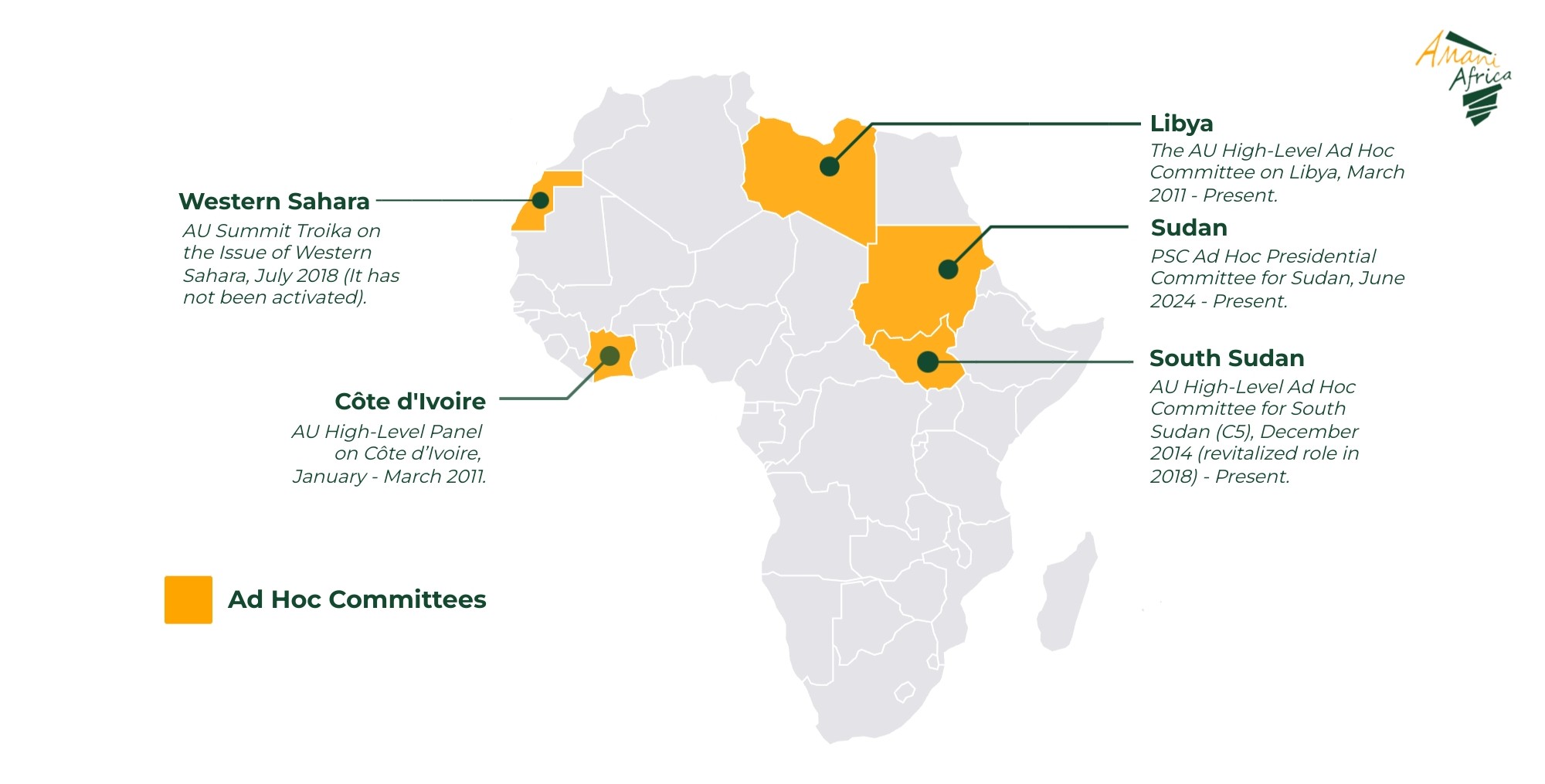

While Article 8(5) of the PSC Protocol envisages the use of ad hoc committees, it did not spell out the level at which such a committee would be established and the form such a committee would take. One of the innovations of the PSC was to constitute the ad hoc committee as an instrument of peacemaking from sitting heads of state and government. For the first time, the PSC established an ad hoc committee at the level of heads of state and government in respect to the conflict in Côte d’Ivoire in January 2011. It was during its 259th session that the PSC decided to establish such a committee, called at the time a high-level panel, for the resolution of the (post-election) crisis in Côte d’Ivoire. The committee was made up of President Mohammed Ould Abdel Aziz of Mauritania, President Jacob Zuma of South Africa, Blaise Campaore of Burkina Faso, Jakaya Kikwete of Tanzania and Idriss Deby Itno of Chad. Since then, the PSC and the AU Assembly have established ad hoc committees in relation to conflict situations in Libya, South Sudan, the AU Summit Troika on Western Sahara and Sudan.

The make-up of these ad hoc committees, from representatives of the five regions of the continent, sought both to ensure ownership of the peace process by all parts of the continent and to enlist the support and engagement of the wider membership of the AU. The fact that the body is also made up of leaders of AU member states that are not necessarily members of the PSC helps create separation of powers for healthy checks and balances. The fact that the ad hoc committees relied on sitting Heads of State and Government also signifies that the situation warrants the attention of the highest authority of AU member states and is indicative of AU’s diplomatic acumen to use the leverage of current leaders from across the continent in the search for a resolution of the situation. As the use of this mechanism for a post-election crisis in Côte d’Ivoire illustrates, these ad hoc committees are deployed not only for peace and security but also for governance crises.

The second group of ad hoc mechanisms for governance, peace, and security deployed by the PSC, which is a complete innovation of the PSC, concerns the high-level panels. The first instance in which the PSC exercised this power was in July 2008, during its 142nd session, when it requested the AU Commission to establish a High-Level Panel on Darfur. Since then, several ad hoc mechanisms have been constituted (see map below for the list of AU ad hoc committees and high-level panels). While most of these mechanisms are initiated by the Council itself, there are also instances where the Chairperson of the AU Commission initiated the mechanisms, with the PSC’s endorsement. The High-Level Panel on Egypt and the mediation process in Ethiopia are examples of such cases. It is, however, worth noting that prior to its use in Sudan, such a high-level panel was constituted by the AU Assembly Chairperson, President John Kufuor of Ghana, in 2008 under the leadership of Kofi Annan for mediating the post-election violence in Kenya.

As the precedent-setting experience of the AU High-level Panel on Darfur and that later transitioned into the AU High-level Implementation Panel on Sudan shows, one of the notable aspects of the peace and security entrepreneurship of the AU in deploying these mechanisms was the use of former heads of state and government. This not only resonates with Africa’s diplomatic and political tradition that cherishes the wisdom of elders but also represents a recognition of the importance of the experience and peer level access that former leaders possess, thereby making them positioned to navigate complex political issues by leveraging their standing and political insights into the dilemmas and concerns that inform the actions of leaders.

It was the effective utilisation of these ad hoc mechanisms during the first decade and a half of the existence of the AU and its PSC that effectively established the role of the AU as the lead peace and security and governance management actor on the continent. Indeed, the experience from these ad hoc governance and peace and security mechanisms offers useful insights into how to re-assert the leadership role of the AU and reposition the African Peace and Security Architecture for a changing global and continental governance and peace and security context. This is particularly critical considering the prevailing context that characterises the time when tomorrow’s session is taking place. One of the features of this period is the decline in AU’s peace and security and governance management role. The combination of the slow pace of response of the AU and the lack of robust political support for its peace and security initiatives as well as the emergence of increasingly assertive states vying for individual mediation role means that increasingly the space for peace and security initiative on African situations such as the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC)-Rwanda and Ethiopia-Somalia tensions and the conflict in Sudan is being taken by non-African states such as Qatar/US, Turkey and Saudi Arabia/US.

In this regard, tomorrow’s session offers a timely opportunity for introspection—to reflect on past and current mediation experiences, particularly those involving ad hoc committees and high-level panels, and their role in advancing PSC’s mandate. What key insights and lessons can the PSC draw from these experiences? The session also takes place against the backdrop of ongoing efforts to review the African Peace and Security Architecture (APSA), including the establishment of a high-level panel by the AU Champion for Institutional Reform, President William Ruto of Kenya. This reflection, therefore, could provide valuable input into the review process.

The analysis of the experience of the ad hoc mechanisms shows that while they have formed part of the AU’s innovative major governance crises and conflict management and resolution tools over the past 15 years, their success has varied. Notably, the AU High-Level Panel on Darfur (AUPD), chaired by former South African President Thabo Mbeki, delivered a landmark analysis that reframed the conflict in Darfur as a manifestation of a broader crisis of governance in Sudan and provided the AU with a clear roadmap on how best the structural issues of peace, justice, reconciliation and healing could be addressed in Darfur. Building on this, the AU High-Level Implementation Panel (AUHIP) was established to implement the AUPD’s recommendations and subsequently to mediate post-secession negotiations between Sudan and South Sudan. By actively seeking and enlisting the support of the region, the PSC, the UNSC and the Troika of the US, UK and Norway, through a clear definition of the issues based on a deductive approach and anchored on a highly professional and technically endowed supporting structure as well as exemplary diplomatic leadership willing and able to dedicate sustained engagement and attention, the AUHIP set the template for successful mediation that registered notable successes including midwifing the peaceful secession of South Sudan and the building of a relatively peaceful post-secession outcome between Sudan and South Sudan. The AUHIP, leveraging the PSC and the UNSC, played a decisive role in averting full-scale war between the two countries following the Heglig crisis in April 2012 and, with the support of IGAD and Ethiopia, brokered eight historic Cooperation Agreements in September 2012 addressing critical post-secession issues. Widely hailed as a ‘wide-ranging, detailed, and historic set of treaties,’ these agreements covered nearly every key aspect of Sudan–South Sudan relations. Equally, if not more successful, experience was the Kofi Annan-led Panel of Eminent Persons that mediated the post-election violence in Kenya.

Meanwhile, other ad hoc mechanisms, such as the PSC ad hoc Presidential Committee for Sudan, have as yet made no headway. Despite being established over a year ago, the ad hoc Presidential Committee has yet to convene its inaugural meeting, even as the conflict escalates and the country edges closer to de facto fragmentation. While the high-level committee on Libya did not succeed in its effort to avert Libya’s descent into state fragmentation and violent conflict, the High-Level Ad Hoc Committee’ (C5) on South Sudan was one of the catalysts for breaking deadlocks between the parties to the Revitalised Agreement for the Resolution of the Conflict in South Sudan (R-ARCSS) that threatened at various points the transitional process in South Sudan.

The analysis of the various ad hoc committees reveals that there are certain factors that are critical for successful AU-led peacemaking and mediation diplomacy. The first of these concerns the composition of the members of the mechanisms and the quality of leadership of the mechanisms. The composition of the mechanism should involve those who not only hold high-level positions—such as former or current heads of state or government—to provide the necessary political and diplomatic weight but also have the tenacity and temperament for providing the process befitting the nature of the crisis or conflict situation. The second lesson is the need for a solid mediation strategy and process that ensures sustained engagement, as illustrated by the AUHIP as opposed to the improvisation-heavy and touch-and-go approach that seems to be the current characteristic of the AU High-level Panel on Sudan. The third lesson highlighted in the Lessons Learned Report from the AU-Led Peace Process for the Tigray Region, Ethiopia, is the need for appointing personalities that have the full confidence of the parties. With Olusegun Obasanjo, who was appointed in August 2021 as the High-Representative of the AU Commission Chairperson charged with facilitating the resolution of the conflict in Tigray, facing charged of bias by one of the parties, it was the decision by the AU to appoint a panel of mediators with the addition of two additional mediators that created the balance that won the full confidence of the parties who agreed to be convened under its facilitation. The other lesson for the success of ad hoc mechanisms from AUHIP to the Ad hoc Committee of 5 on South Sudan to the AU High-Level Panel on the Ethiopian Peace Process is the imperative for strong coordination with and mobilisation of support from key regional and international actors. Not any less significant is the quality of the support structure, including qualified technical experts and adequate financial resources, that is put in place for facilitating the effective functioning of the ad hoc mechanism. The African Union Panel on Darfur (AUPD) benefited from the contributions of nine prominent experts, while the African Union High-Level Implementation Panel (AUHIP) drew on a wide range of technical expertise from across the globe, including specialists in oil, economics, law, border demarcation, and other relevant areas. This expert input was further complemented by support from AU staff. AUHIP is not unique in this. The panel of mediators led by Kofi Annan that was enlisted to mediate the post-election violence in Kenya in 2008 by the then Chairperson of the AU Assembly, Ghana’s President John Kufuor, similarly enjoyed a robust support structure. Some of the current mechanisms, such as the AU High-level Panel on Sudan, do not seem to be as endowed with such robust structures as the AUHIP or the Kofi Annan-led AU mediation on the post-election crisis in Kenya. In terms of mobilisation of requisite financial support, the AU’s partnership with the African Development Bank (AfDB), which availed funding for the Ethiopia mediation process, offers a useful example of leveraging the contribution of various entities in supporting AU ad hoc mechanisms.

The expected outcome is a communiqué. The PSC is expected to underscore the vital role of ad hoc governance, peace, and security mechanisms in fulfilling its mandate on conflict prevention, management, and resolution. It may reaffirm the importance of the ongoing APSA review as a necessary step for the AU to adapt to evolving regional and global dynamics. While welcoming the ongoing efforts in this regard, the PSC may use the opportunity to highlight the need to revitalise the AU’s preventive diplomacy and mediation efforts, and to re-establish diplomacy as the primary instrument for achieving peace and security on the continent. In this context, the PSC may stress the importance of enhancing the use of ad hoc mechanisms as part of the APSA review process, drawing on insights and lessons learned from successful past experiences in deploying these mechanisms across Africa. Emphasising the need for a robust support system to ensure the effective functioning of these mechanisms, the PSC may also call for the strengthening of the AU’s conflict prevention, management, and resolution structures, particularly the Mediation and Dialogue Division, the Continental Early Warning System and the Panel of the Wise.