Education in Conflict Situations

Date | 12 August 2025

Tomorrow (13 August), the African Union (AU) Peace and Security Council (PSC) will convene its 1296th open session, focusing on education in conflict situations.

The Permanent Representative of Algeria to the AU and Chairperson of the PSC for the month of August 2025, Mohamed Khaled, will deliver opening remarks, followed by Bankole Adeoye, AU Commissioner for Political Affairs, Peace and Security (PAPS). The PSC will receive presentations from Prof. Mohammed Belhocine, Acting Commissioner for Education, Science, Technology and Innovation (ESTI) and Wilson Almeida Adao, the Chairperson of the African Committee of Experts on the Rights and Welfare of the Child (ACERWC). Rebecca Amuge Otengo, Permanent Representative of Uganda to the AU, and Co-Chair of the Africa Platform on Children Affected by Armed Conflicts (AP-CAAC) and the Representative of the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), will also brief the session.

The last time the PSC convened a session on the theme was at its 1229th meeting, held in August 2024. In that session, the PSC resolved to institutionalise education in conflict as an annual thematic focus. It also stressed the need to uphold the right to education for all, even in conflict, urging Member States to adopt conflict-sensitive, crisis-resilient policies, strengthen data-driven policymaking, integrate inclusive education into post-conflict recovery and appoint a Special Envoy on Children in Conflict. The upcoming session also precedes the 2025 AU Education Summit, intended to mobilise Member States and stakeholders around the continent’s educational priorities. The session is expected to first examine the current state of education in conflict and post-conflict settings, with attention to the systemic collapse of educational services caused by ongoing violence and institutional fragility.

Armed conflict and instability are significant barriers to education in Africa, depriving millions, especially girls, children with disabilities and displaced populations, of safe and inclusive learning. Attacks on schools, the militarisation of facilities and child recruitment erode national education systems, deepening poverty and inequality. In many conflict zones, school closures remove vital protection and create a causal link between attacks on education and the rise in harmful coping mechanisms, particularly child marriage. The loss of schooling exposes adolescents, especially girls, to heightened risks of violence, displacement and economic hardship, reinforcing cycles of vulnerability and deprivation.

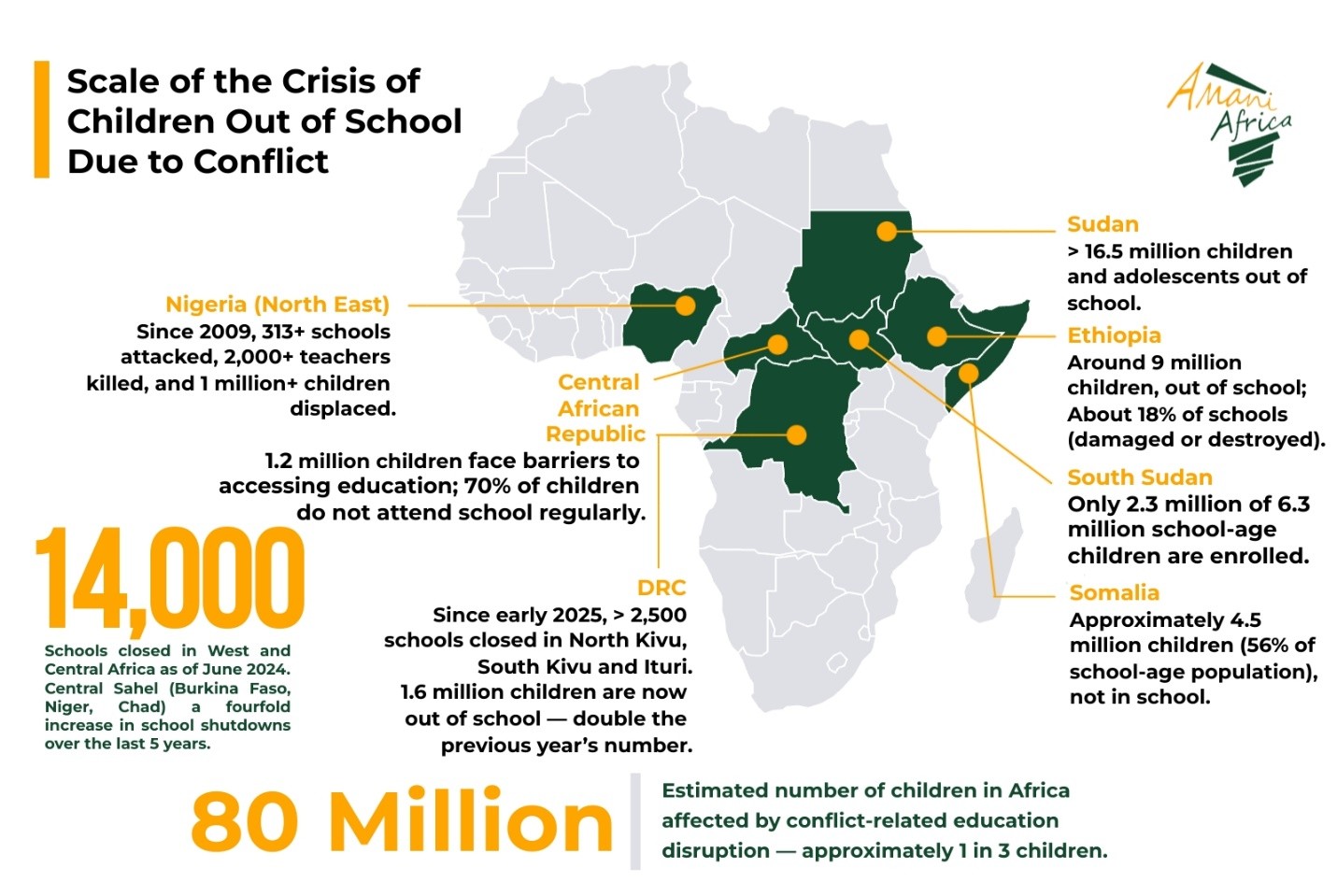

Conflict continues to severely undermine access to education across Africa, with an estimated 80 million children affected, amounting to ‘one in three’ on the continent. In West and Central Africa, insecurity has led to the closure of over 14,000 schools as of June 2024. The Central Sahel region has seen a ‘fourfold increase’ in school shutdowns over the past five years, disrupting education in Burkina Faso, Niger and Chad.

The gravity of the situation is most acute in Sudan, where the ongoing armed conflict has produced one of the continent’s worst education emergencies. Recent estimates place the number of out-of-school children and adolescents at over 16.5 million. Many of these children reside in displacement sites, often with no access to formal education. Prolonged violence has severely disrupted learning, with attacks on schools and the militarisation of educational facilities compounding an already fragile system.

In Ethiopia, an estimated 9 million children remain out of school due to the compounded impact of conflict, climate-related disasters and displacement. Around 18% of educational institutions have either been damaged or destroyed, particularly in conflict-affected regions. This has further aggravated school dropout rates and negatively affected female students, especially in rural and border areas.

In Somalia, data from humanitarian partners indicate that approximately 4.5 million children—representing 56 per cent of the school-age population—are currently out of school. Insecurity, displacement and a lack of access to basic services have left children particularly vulnerable to violence, exploitation and recruitment by armed groups.

In the Central African Republic, conflict continues to affect education severely. Despite a reduction in violence in some areas, 1.2 million children still face significant barriers to schooling, with ‘seven out of ten’ not attending classes regularly. The country has also witnessed attacks on education infrastructure, further straining the capacity of national authorities and humanitarian partners to deliver education in affected areas.

In Nigeria, the northeast region has suffered for over a decade of insurgency. Since 2009, more than 313 schools have been attacked, over 2,000 teachers have been killed, and more than one million children have been displaced. Boko Haram’s systematic targeting of education represents one of the clearest cases of education being weaponised as part of a broader ideological conflict.

In South Sudan, protracted violence has left ‘only about 2.3 million of the country’s 6.3 million school-age children’ enrolled in school. Conflict-related displacement, combined with inadequate infrastructure and limited teacher deployment, continues to hinder educational progress, especially for children residing in camps or border regions.

In the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), more than 2,500 schools in the eastern provinces of North Kivu, South Kivu and Ituri have been closed since early 2025. Many of these buildings have been damaged or repurposed, leaving an estimated 1.6 million children out of school in the region—nearly double the previous year’s figures.

In this context, the open session is expected to consider a broad range of strategic responses, including urging Member States to accelerate the domestication and effective implementation of the Safe Schools Declaration (SSD), adopted in 2015 and endorsed by 33 African states. This global intergovernmental commitment seeks to advance the protection of education, restrict the use of schools and universities for military purposes, collect data on attacks against educational facilities and victims, ensure the continuation of learning during conflict and investigate violations to deliver justice and assistance to survivors. These efforts form part of a broader agenda to prevent the military use of educational facilities, strengthen legal protections for learners and educators and establish local monitoring and reporting mechanisms for attacks on education. Within this framework, discussions are anticipated to align with the Continental Education Strategy for Africa (CESA) 2026–2035, particularly Strategic Area 6, which prioritises inclusive education for marginalised and crisis-affected populations.

A key priority will be ensuring the continuity of learning during emergencies. Integrating education contingency planning into national crisis response strategies is expected to be one of the discussion points in tomorrow’s session, reflecting commitments articulated in the Nouakchott Declaration of December 2024 that declares 2025-2034 as the ‘AU Decade of Accelerated Action for Education Transformation, Youth Skills Development and Innovation in Africa’. The declaration commits to safeguarding the right of children and youth to quality education in all circumstances, including during conflict; integrating education in emergencies into national education strategies to enhance system resilience; ensuring schools are protected from attack or military use in line with the SSD; advancing peace education and safe learning environments by embedding violence prevention and response in curricula and adopting conflict-sensitive approaches, especially in humanitarian and fragile contexts; and promoting peaceful conflict resolution while supporting the AU’s ‘Silencing the Guns by 2030’ initiative to foster inclusive learning, particularly in protracted crises. The PSC is expected to promote contingency planning, mobile classrooms and alternative forms of delivery such as digital and radio-based learning—backed by the AU Digital Education Strategy (2023–2028). Enhanced capacity-building for local education actors, support for trauma-informed education and better coordination with civil society are likely to be encouraged to sustain educational continuity in crisis-affected regions.

The session is also expected to devote substantial attention to the psychosocial impacts of conflict on learners. The recent 1290th meeting voiced concern over the rising recruitment of children by armed forces and groups, noting that released children often face severe psychological distress, social stigma and exclusion from education. In response, the current session is likely to advocate integrating mental health services into education systems and providing trauma-informed teacher training to build resilience, improve learning outcomes and prevent long-term harm. Echoing the 597th meeting’s alarm over sexual violence and attacks on educational infrastructure, the PSC may revisit calls—aligned with UN Security Council Resolutions 2143 (2014) and 2225 (2015)—to deter the military use of schools.

Discussions may also explore the link between conflict and the high prevalence of out-of-school children, including those recruited as child soldiers, as highlighted in the 706th meeting’s call for robust child protection frameworks within the AU Commission covering education, health and security. Emphasis may be placed on AU instruments such as the African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child, particularly Article 22, prohibiting child recruitment, and on ensuring the protection and care of children who are affected by armed conflicts. The PSC could further call for stronger coordination between the AU’s Departments of Social Affairs and PAPS to address these issues comprehensively. Stronger inter-ministerial frameworks and improved cooperation between AU bodies such as the African Humanitarian Agency and African Risk Capacity could be highlighted as critical to delivering holistic and effective responses.

Furthermore, education in peace support operations (PSOs) will be addressed as a pillar of post-conflict reconstruction and development (PCRD). Embedding peace education, supporting the reintegration of former child soldiers through education and training peacekeepers to protect learning spaces will all be positioned as strategic components of broader peacebuilding agendas.

Particularly significant for the session is the expected focus on the critical challenge of financing education in emergency settings. Among the proposals likely to be explored are the establishment of pooled funding arrangements and the targeted use of the AU Peace Fund to finance infrastructure rehabilitation, teacher deployment and trauma-informed educational programming. Mobilising adequate and sustained financing, notably to support education for children affected by conflict, will require stronger coordination and alignment of donor contributions with continental frameworks.

The other important area of deliberation is expected to be strengthening data and monitoring systems. Improving the AU Education Management Information Systems (EMIS) could be explored as a strategy to enhance policies and practices that reinforce Member States’ national education systems, to achieve equitable quality education for all (Sustainable Development Goal (SDG 4)) and accelerating CESA implementation. This may include promoting EMIS use to track attendance, safety and learning outcomes in conflict settings, as well as supporting Member States in reporting on SDG 4.

The expected outcome of the session is a communiqué. The PSC may voice grave concern over armed conflict’s impact on education and its implications for Agenda 2063, reaffirming Member States’ commitment to safeguarding education in conflict and post-conflict contexts. It may urge integration of protection and recovery measures into AU PSOs and PCRD frameworks with accountability mechanisms, call for stronger coordination across sectors, increased domestic funding, and alignment of international support with CESA 2026–2035 and Agenda 2063. The PSC could recommend AU Guidelines on Education in Conflict, commission a Health, Humanitarian Affairs and Social Development (HHS)–ESTI study on links between attacks on education and harmful practices, and push for faster domestication and implementation of the SSD. It may also promote integrating child protection and education into the Silencing the Guns initiative, encourage endorsement of the SSD by non-signatories and strengthen implementation by signatories. It may also emphasise stronger coordination among AU sectors working on education, peace and security, humanitarian affairs and social development, and propose a continental platform or task force to monitor and respond to education crises in line with the CESA Cluster on Education in Emergencies. Additionally, it could propose a continental platform for crisis response coordination and an observatory to track child marriage trends in conflict settings for targeted interventions.