As part of covering some of the major themes on the agenda of the AU summit, this Ideas Indaba presents analysis on preparations for and modalities of organizing AU’s participation in G21.

How Africa organizes itself will make or break AU’s G21 membership

Date | 2 February 2024

Faten Aggad

Member of the Namibia-Amani Africa High-Level Panel

Solomon Ayele Dersso, PhD

Founding Director, Amani Africa

The decision of the India G20 summit last September admitting the African Union (AU) as a permanent member has been hailed as a historic development both continentally and globally.

While it is not true that the benefit of AU membership to the global body is insignificant, there is merit to the view that the potential benefits of AU’s membership for Africa are significant. AU’s G21 membership can transform Africa’s position from being a passive receiver (object) into an active contributor (agent) of global financial and economic policy-making. This could be consequential particularly when such policy-making affects Africa’s social and economic interests directly or substantially.

Needless to say, the mere fact of AU’s membership in the G21 will not be enough to harness the opportunities that membership in G21 presents for Africa. Seizing these opportunities depends mainly on AU’s effective participation and exertion of influence in shaping both agenda setting and negotiation of policies in the group.

A critical pre-requisite for such participation and influence is the establishment of politically legitimate, technically equipped and operationally dynamic institutional arrangement and processes. Now that it secured a seat at the table, it is time for the AU to properly address the question of such institutional arrangement and processes that facilitate the effective planning and active participation of the AU in the G21 processes.

While the discussion on how to go about AU’s membership in the G21 picked pace only few months after the India presidency summit in September, this discussion in the AU reveals both a clear recognition of the weight of the responsibility and commitment for crafting the institutional arrangement and processes necessary for AU’s meaningful use of its membership in the G21.

Thus, following the meeting of the AU Permanent Representatives Committee (PRC) on 8 December, a PRC Sub-Committee on the Working Group on Modalities and Participation of the AU in G20, headed by Emilia Ndinlao MKusa Namibia’s Permanent Representative to the AU, was tasked to work with Albert Muchanga, the AU Commissioner for Economic Development, Trade, Tourism, Industry and Minerals to develop options on how to organize AU’s role as member of the G21. For its part, the AU Commission constituted a high-level taskforce co-chaired by the Commission’s Director General and Muchanga. Following the meeting of the PRC Sub-committee Working Group on 12 January, a report outlining options on modalities and priorities on AU participation in the G21 and draft decisions for adoption by 37th AU summit to be held during 14-18 February 2024 have been prepared.

As commendable as this recognition and commitment of the AU as well as the work accomplished this far are, what matters the most is the choices that the AU makes on both the structures/entities that represent the AU, present and defend its policy position at the various levels of G21 negotiations and the internal processes for preparing, negotiating and adopting AU’s policy positions. Thus Muchanga rightly observed during the 12 January PRC meeting that ‘effective collaboration between the AUC and Member States is critical to facilitate coordination and ensure that Africa speaks with one voice.’ A major dilemma that the AU faces and the policy discussions thus far reveal is the balance that should be struck between political legitimacy and institutional and technical competency that are key for effectiveness of AU’s membership.

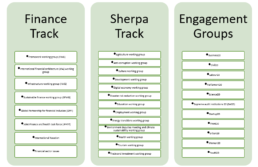

It is, therefore, important to ensure that the AU membership is supported by adequate, mandated preparatory processes and politically astute and technically robust representation in both the G20 Tracks (see Visual 1) as well as the thematic priorities of each G20 Presidency.

More specifically, the following points provide recommended inputs for a possible roadmap currently being proposed for AU summit to ensure an effective engagement of Africa in the G21:

1.The AU representation at G20 summit: Unlike other regional representation at the G20 (i.e. the EU), the AU (Union Chair and Commission) does not have delegated authority to act on behalf of AU member states on most issues covered by a typical G21 agenda. Therefore, the working methods are key to define the scope of engagement while ensuring that the AU reaps maximum benefits from its G21 membership.

In formulating the working methods, member states will need to strike a balance between, on the one hand, the imperative of inclusivity through adequate consultations of AU Membership, and, on the other hand, speed considering the pace of G21 processes.

In this respect, the AU could consider adopting an approach whereby, based on the incoming G21 Presidency announced priorities, the AU Chair, supported by the AU Commission, presents its detailed engagement proposal for consideration by the AU decision making structures during the annual AU Summit. Such engagement mandate would be subject to debate and refinement after which it could be adopted as guidance to the AU Presidency in its engagement.

2.Coordination at Assembly level in between AU summits: the AU can consider and use two avenues for this. First, the experience thus far including best practice following the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic shows the role that the Bureau of the AU Assembly could play for coordination in between AU summits. This has allowed a degree of continuity in the AU agenda and shall provide an excellent basis for the continent’s engagement in the G20 through close coordination between presidencies. The G20 should therefore be included in the coordination efforts of the Bureau and should be a standing item in their meetings. Second and as proposed in the conclusion of the 12 January PRC meeting is for the AU Executive Council to deal with G20 matters during its mid-year meeting on the basis of delegated authority from the AU Assembly.

3.Clarifying representation beyond the leaders’ summit: while the 2023 AU Summit Decision is clear about who represents the Union at G20 Summit, the G20 also meets at the level of Foreign Ministers. The upcoming AU summit needs to decide on AU’s participation at this level. This can be guided by the model of representation at the summit level and may as such assign the Chairperson of the Executive Council of the AU, assisted by the AU Commission, to represent the AU in the G20 Ministers of Foreign Affairs Meeting

It is worth noting that the heavy lifting of G20 meetings is done by the Sherpas, supported by the sous-Sherpas. During the 12 January meeting the PRC discussed the two options of designating the AU Sherpa to the G20: a) from the country Chairing the Union that year and the Sous-Sherpa from the AU Commission and b) from the AU Commission, preferably the Commissioner for Economic Development, Trade, Tourism, Industry and Minerals and the Sous-Sherpa from the country chairing the AU.

The proposal on the table is to have the Sherpa from the country chairing the AU and the Sous-Sherpa from the AU Commission. This has the advantage of balancing political legitimacy and institutional and technical responsibility. It also aligns representation where much of the heavy lifting is done with the summit decision on AU representation at G20 summit.

In order to address the issue of continuity at the level of the Sherpa, the AU may also wish to consider a consultation framework involving the Sherpa and the incoming Sherpa. The implication of this is that the incoming chairperson of the AU would designate the person who would serve as the incoming Sherpa.

Furthermore, the G20 Finance Track is led by the finance ministers and central bank governors. Unlike the EU, the AU does not have an African Central Bank. It is critical for the AU to tap into the role of Specialized and Technical Committees that have mandates relevant to the sectoral ministerial meetings of the G20. Here, as with the approach with respect to the Sherpa and Sous-Sherpa, important to have a balance between political representation and accountability and institutional and technical responsibility. In this respect, it is essential to draw on the role of both the relevant AU Commission department specifically the directorate responsible for finance and that of the association of African Central Bank Governors.

4.Consultation of the wider AU membership in the formulation of the AU common position on G20 matters: the effective representation of AU in the G20 depends on the support and buy in of the wider AU membership considering that neither the AU Chairperson nor the AU Commission have delegated sovereign authority. This is where the role of the Permanent Representatives Committee and its relevant sub-committee/s become crucial. At this level, the relevant sub-committee, namely that of Economic and Trade matters, can be assigned with the role of anchoring the G20 file at the level of the PRC.

Beyond this participatory consultation framework, the formulation of common position necessitates that there is deeper and more enhanced harmonization of economic, financial and trade policies of African states. It is thus critical that as part of the effort to enhance AU’s effective membership priority is given to speeding up the operationalisation of relevant AU bodies such as financial institutions that could facilitate this process of harmonization of policies.

5.Technical support: with its considerable number of annual meetings, the G21 process is time-consuming and technically demanding. While creating important opportunities, the G21 engagement will require significant investments from the AU system. It is therefore important to put in place adequate support structure for the AU’s role in the G21. This could take the form of a hybrid technical team that is composed of a team of technical advisors from the member state chairing the Union, the Commission, the Bureau, AU specialised agencies (AUCDC, AMDC, AFREC, ARC, ACBF, etc), partner institutions (UNECA, AFRIXEMBANK, AfDB, etc.) and African specialists drawn from relevant think tanks. This standing technical unit could be hosted under the office of the Chairperson of the AU Commission or under AU AUDA and should be strictly financed from the AU Budget.

6.Ensure coordination between African G21 members – apart from South Africa, which is a permanent member of the G21, individual African member states are also invited to attend the G20 summit by the G20 presidency. This necessitates that there is close coordination between the AU Chairperson, South Africa and the other African states that get invited into the G20 summit. Such coordination is a prerequisite for ensuring that Africa speaks with one voice.

7.Clarify the financing source. The independence of the African agenda in the G21 is of paramount importance due to its direct implications on African countries’ economies and finances. The current global geopolitical context makes it even more critical. Therefore, as much as possible, the AU engagement in the G21 should be financed through the AU budget and sources mobilized from within the continent and pan-African institutions.

Now that Africa has a seat at table, we hope that the ideas in this brief complement the ongoing work in the AU to ensure that Africa uses its seat to shape the making of the menu as well.

The content of this article does not represent the views of Amani Africa and reflect only the personal views of the authors who contribute to ‘Ideas Indaba’