The coup in Niger: Lessons from a trouble in paradise

Date | 31 July 2023

Solomon Ayele Dersso, PhD

Founding Director, Amani Africa

Lea Mehari Redae

Associate Researcher, Amani Africa

After two earlier unsuccessful attempts, the latest usurpation of power by Niger’s army succeeded in ousting the country’s elected President, ending the last central Sahel country under civilian rule. Niger has been put on a pedestal. As a country where the incumbent respected presidential term limits and transferred power to a successor after the holding of elections in 2021, Niger was portrayed as an island of democracy in a sea of military coups and terrorism. During his visit to Niger US Secretary of State Anthoni Blinken praised Niger as ‘a model of resilience, a model of democracy, a model of cooperation.’

For a country with such standing, the coup that took place on 26-28 July ousting Niger’s elected President may come as a trouble in paradise. Certainly, it is a major blow to the country’s fragile democratization process. Even more troubling is the constitutional and political uncertainties the coup induces may compound the country’s fragilities. These uncertainties would detract from the effort to contain the terrorism menace unfolding in the country. There is also a huge risk that it exacerbates the geopolitical rivalry unfolding in the region by rendering the country to be a theatre of the power tussle that Niger’s neighbours became victims of.

Yet, the attempted coup in March 2021 made it apparent that Niger was not free of the threat of military seizure of power. France 24 reported quoting a Nigerien official that while the President was in Turkey ‘a second bid to oust Bazoum occurred last March.

Niger also shares some of the fragilities that characterise the central Sahelian countries, although it fared better than its immediate neighbours and avoided the crisis that befell Mali following the collapse of Libya in 2012.

Niger’s democratic credential shares some of the characteristics of Mali’s prior to 2012. Like Niger, Mali prior to 2012, was viewed as an example of democracy in the region. This view is best summed up by one analyst who asserted that ‘Mali has achieved a record of democratization that is among the best in Africa.’ As the events in 2012 revealed and many admitted, Mali’s democracy was not much more than electoral democracy.

Like Mali, Niger’s democracy is bereft of substantive depth that goes beyond elections. According to Afrobarometer’s 2020 survey, despite 53% support for democracy in Niger, 67% of Nigerians surveyed thought that the army ‘can intervene if leaders abuse power.’ Unless democracy is reduced to relatively free elections, it is difficult to imagine why citizens consider military intervention in politics as a first choice for holding leaders to account. A major factor that may account for such attitude is the absence or poor performance of the constitutional mechanisms in a democracy such as separation of powers and checks and balances, independent judiciary, free media and open civic space with autonomous civil society.

Apart from the public attitude to military intervention, the other context for the coup involves the widespread perception of President Bazoum administration’s deepening ties with France and the West in the face of the spreading anti-French sentiment in much of Francophone Africa. In other words, putting Niger on a pedestal might inadvertently have exposed Bazoum’s administration to be on a collision course with Nigeriens opposing to Niger becoming the new hub for France’s operation against terrorist groups in the Sahel as protests earlier in the year showed.

None of the foregoing however makes the coup right, although these could limit public opposition against the coup. Indeed, despite the excuse by the junta that the coup was staged due to ‘the continuing deterioration of the security situation and poor economic and social governance’, the coup mostly has to do with greed and personal interests of those who led it. The actual motivation for the coup is immediately tied to President Bazoum’s plan to replace the leader of the Presidential Guard, General Abdourahmane Tchiani, who took over as Niger’s leader.

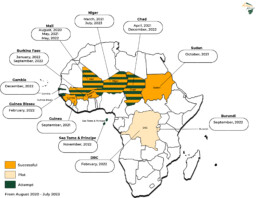

The coup in Niger is the seventh successful coup to take place in Africa since 2020. Six countries stretching from the Atlantic coast in the West to the Red Sea coast in East Africa are being led by men in uniform.

The epidemic of coups, as UN Chief characterized it, is, among others, a result of the crisis of governance of the security sector. The coup in Niger manifests the lack of total break from the experiences of politicization of the armed forces and the militarization of politics associated reflected in the number of successful and attempted coups in the country. As the attempt by Tchiani to forestall his planned replacement shows, the coup also shows the poor level of professionalism and integrity of the military. All of these suggest that democracy in its electoral form will remain susceptible to the vagaries of the army as long as these issues of the crisis of security sector governance are not effectively resolved.

In response to the latest coup in Niger, apart from the unanimous condemnation from AU, UN & other international entities, the regional body ECOWAS adopted the most severe measures including closure of borders & airspace, suspension of economic & financial exchanges and threat of military intervention. These may not be enough to reverse the coup without support from Nigeriens. This highlights that it is utterly inadequate for regional and continental norms to be effective in discouraging coups and other unconstitutional seizure of power to be dependent largely on external mechanisms of protecting constitutional order. More often than not, these norms are not adequately backed by national level robust formal and informal processes and institutions of accountability and checks and balances. They are further undermined by governing elites tampering constitutions including presidential term limits.

The failure of the anti-coup norms of the AU to prevent coups is not thus merely a result of the lack of effective enforcement and consistent application of the norms on the part of the AU. It is also attributable to the lack of mobilizing and nurturing of anti-coup constituency on the part of the African public at the national level. This emphasizes that continental and international actors have to rethink the dominant approaches to democracy that are election centric and to international relations, including development and security cooperation, that are elite-driven. Not only that continental and international actors need to avoid downplaying the political and socio-economic grievances of local populations against national authorities. Their engagement and development and security cooperation should go beyond the security sector and national elites and extend to the human security, political freedom and development needs of local populations as well.

The upshot of the foregoing is that there is a need for rethinking both democracy promotion and counterterrorism security cooperation in Africa anchored on the primacy of the local. As Amani Africa’s research on terrorism asserted, such a paradigm shift necessitates policy interventions that focus ‘on the vulnerabilities and fragilities as well as political and socio-economic governance pathologies that create the conditions both for the emergence and … resilience of terrorist groups’ as well as coups. With such policy interventions that also entail ‘the same, if not more, level of infusion of technical assistance, financial resources and training of civilian expertise is directed to the governance, the economic and social issues facing local populations as the security-related sectors’, it is possible to mobilize a public that would become a bulwark against coups and other threats to constitutional order and security.

The content of this article does not represent the views of Amani Africa and reflect only the personal views of the authors who contribute to ‘Ideas Indaba’