The state of Maritime Security in Africa

Amani Africa

Date | 23 July, 2021

Tomorrow (23 July) the African Union (AU) Peace and Security Council (PSC) is set to convene its 1012th session on the state of maritime security in Africa.

Following the opening remarks of the Chairperson of the PSC, Victor Adenkunle Adeleke, the AU Commissioner for Political Affairs, Peace and Security (PAPS), Bankole Adeoye, is expected to make a statement.

Given the increasing maritime insecurity in the continent, tomorrow’s session presents the Council the opportunity to assess the overall maritime security situation of the continent with particular focus on the Gulf Guinea, receive update on the status in the implementation of regional and continental maritime security frameworks, as well as explore ways and means to effectively respond to maritime insecurity in the continent.

As recent data demonstrates, incidents of piracy and kidnapping for ransom of seafarers continue to be major challenges along the Gulf of Guinea. According to reports of the International Maritime Bureau (IMB), the region experienced 50% increase between 2018 and 2019, and 10% increase between 2019 and 2020 in incidents of kidnapping for ransom. In 2020 alone, there were 84 attacks on ships and 135 kidnappings of seafarers. In the first three months of 2021, the region accounted for 43% of all reported piracy incidents while over 14 crew members were abducted in three incidents of kidnappings recorded within the year so far. Currently, the region is said to account for just over 95% of all kidnappings for ransom at sea. In addition to piracy and kidnapping for ransom, the region is also highly prone to other maritime crimes including armed robbery, transnational organised crime, illegal fishing, and illegal trafficking and smuggling of goods.

In addition to the increase in maritime crimes, studies also indicate the increasingly violent nature of such incidents. For instance, the use of guns was reported in 80% of kidnappings for ransom which took place during 2020. This is a sharp shift from the nature of piracy experienced in the region a few years back, which was limited to occurrences of cargo theft. Another growing trend in the nature of maritime crimes in the Gulf of Guinea is the broadening and extension of risk zones. That is, while most cases of piracy and kidnappings initially used to take place within the territorial waters of coastal States, the more recent incidents tend to take place further from shores and within the high seas – at 200 nautical miles from the coastline according to data recorded by the IMB. These trends in turn underscore the importance of strengthening international and regional efforts and collaborations aimed at addressing the risks to maritime security in the region.

Because most of the security challenges in the Gulf of Guinea previously took place under 200 nautical miles from coastline, States in the region resisted the idea of an international presence to respond to maritime security threats which were usually categorised as armed robberies as opposed to piracy. With the distance from shorelines highly increasing and the nature of crimes also getting more volatile, the incidents in the Gulf of Guinea are nowadays prompting comparisons with piracy in the horn region, along the coastline of Somalia. Although shipping companies operating in the region are growingly showing support for international responses, it is more likely that Gulf of Guinea States would prefer continued support from the international community to boost their capacity in averting threats to maritime security instead of handing over the responsibility to outside entities.

While reflecting on possibilities of new international responses is important, it is also essential to emphasise the importance of effective implementation of existing regional frameworks such as the Yaoundé Code of Conduct and the African Charter on Maritime Security, Safety and Development in Africa (Lomé Charter) in order to effectively address maritime security challenges in the region. At its 858th session dedicated to the same theme, the PSC focused on the finalisation, signature and ratification of the draft Annexes to the Lomé Charter. The upcoming session presents Council the opportunity to follow up on the status of the draft Annexes which are basically aimed at incorporating within the Charter, all relevant AU structures, particularly those relating to economic mandate and were not involved in the development of the Charter. The pilot case of the European Union (EU)’s Coordinated Maritime Presences (CMP) concept, launched at the meeting of the Council of the EU on 25 January 2021 is also one of the most recent efforts representing international collaboration to address maritime security challenges in the Gulf of Guinea. The CMP establishes the Gulf of Guinea as a Maritime Area of Interest (MAI) and aims to support coastal States in addressing challenges which undermine maritime security and good governance in the region.

At the national level, it is also crucial to properly identify and take timely measures against the root-causes of piracy and other maritime crimes including poverty, high rate of youth unemployment, poor governance, lack of education, and weak law enforcement. In addition to locally addressing the underlying causes of maritime crimes, States in the region also need to harmonise their domestic laws with regional and international standards. In this regard, Nigeria’s anti-piracy laws (such as the Suppression of Piracy and other Maritime Offences Act of 2019 which prescribes stringent punishments against crimes committed in the maritime domain) and the initiatives such as the Deep Blue Project (launched in 2019 with the central goal of addressing insecurity and criminality in Nigeria’s territorial waters) could serve as lessons for more mobilisation of similar enterprises across the region.

It is also important to pay due regard to the economic impact of maritime insecurity and the constraints it imposes to the flow of trade and investment. As the Gulf of Guinea continues to growingly be regarded as one of the most dangerous shipping routes and insecure maritime environments in the world, the risk to economic development in the region, as well as the continent at large, also increases. Particularly with 90% of trade to west Africa coming by sea, the region’s economy is largely affected by concerns of maritime security. Not only is there a likelihood for the region’s reputation as a dangerous route to ward off potential traders, the increasing level of insecurity also inevitably results in the rise of business costs and increase in price of goods and services. While this has the potential to eventually devastate the economy of coastal States in the long-run, it also directly affects the livelihood of populations in the region. Hence, it is essential for response mechanisms crafted under any national, regional or international initiatives to take account of the economic aspect of maritime insecurity in the region.

The outcome of tomorrow’s session is expected to be a communiqué. In addition to reflecting on the security concerns along the Gulf of Guinea, Council may remark on the importance of strengthening Africa’s continental capacity to respond to security threats in the maritime domain, including through taking solid steps towards the implementation of the 2050 African Integrated Maritime Strategy. Council may also call on member States in the Gulf of Guinea to fortify their efforts through, among others, information sharing; interdicting suspicious ships; and apprehending and prosecuting suspected criminals in line with the Yaoundé Code of Conduct. It may also encourage littoral States to allocate sufficient funds for building up local and regional response mechanisms against maritime security threats. Having regard to the growing trend in further offshore incidents of maritime crimes in the Gulf of Guinea, Council may also stress the need for a more integrated regional approach towards addressing the challenges. Council may also note the low level of ratification of the Lomé Charter and urge member States that have not yet done so, to sign and ratify it (as of 2020, only two of the 35 AU member States that have signed the Charter have ratified it). The AU Commission may also be requested to take the necessary steps towards the finalisation of the draft annexes to the Lomé Charter.

Session on the Common African Position on the Financing of AU led Peace Support Operations through UN Assessed Contributions

Amani Africa

Date | 21 July, 2021

Tomorrow (21 July) the African Union (AU) Peace and Security Council (PSC) is scheduled to hold a session on the common African Position on the Financing of AU led peace support operations through UN assessed contributions. The Commissioner for Political Affairs, Peace and Security (PAPS), Bankole Adeoye is expected to brief the council on the progress and state of development of the common position.

The AU Assembly in its decision of its 14th extraordinary summit requested the PSC to articulate a common African position on financing peace support operations in Africa, to guide the African Members of the UN Security Council (A3) in championing and mobilizing support within the UNSC for adoption of a resolution that will enable Africa to access UN assessed contribution for peace support operations in the Continent.

It is also to be recalled that the PSC at its 881st session held in September 2019 took a view that ‘a better articulated and African owned common position’ before a draft resolution on financing of AU peace operations through UN assessed contributions is tabled for consideration by the UN Security Council (UNSC). This decision was taken against the background of issues that emerged as the A3 members of the UNSC were seeking during 2018 and 2019 to secure a UNSC resolution authorizing in principle under agreed upon conditions the use of UN assessed contributions for AU led UNSC authorized peace support operations on a case-by-case basis.

The A3 spearheaded by Ethiopia initiated a draft resolution on financing to be adopted in December 2018 under the Cote d’Ivoire Presidency of the Security Council. However, the US threatened to Veto the resolution. Following the introduction of a so- called compromise text proposed by France to accommodate the US, the vote on the A3 draft resolution was postponed (Please refer to the Amani insight on this issue). South Africa, who initially brought the issue of financing to the Security Council in its previous membership, made the issue one of the priorities of its tenure during 2019-2020. After holding consultations on the matter including a visit by the Permanent Representatives of the A3 to Washington, D.C. to engage with the United States, including the Congress, White House and the Department of State, South Africa introduced a new and slightly updated text from the initial A3 draft and the so-called compromise draft.

When the PSC finally reviewed the matter, it felt that the latest updated draft did not adequately reflect AU interests. The PSC opted for deferring the consideration of the draft text by the UNSC pending the holding of adequate consultation at the level of the AU leading towards a common position. This aims at providing greater clarity on various issues, including on the implementation of the 75/25 formula and on the operationalization of the AU Peace Fund and its role for burden sharing. The common African position elaborated by the Commission is expected to explain some of these issues in order to ensure greater understanding and consensus within the AU and help the discussion in the UNSC move forward.

During tomorrow’s session Commissioner for PAPS, Adeoye, who revived the process for the adoption of the common position, is expected to provide update to the PSC on steps taken towards the elaboration of the common position and the orientation of the common position that will be the basis for resuscitating the discussion on A3 sponsored resolution on financing AU peace operation through UN assessed contributions. The common position is expected to take stock of and build on the various efforts undertaken both at the level of the UN and the AU.

It is worth noting that the issue of predictable and reliable financing has been one of the longstanding subjects in the AU-UN relationships on peace and security in Africa. In 2008, the UN Panel led by former Italian Prime Minister Romano Prodi on the subject recommended in its report the use of United Nations-assessed funding to support United Nations- authorized African Union peacekeeping operations for a period of no longer than six months. This was further reinforced by the UN’s 2015 High Level International Panel on Peace Operations (HIPPO) Report, which recommended the use of United Nations-assessed contributions on a case-by-case basis to support Security Council-authorized African Union peace support operations including the costs associated with deployed uniformed personnel to complement funding from the AU and/or African Member States.

On the part of the AU, the Policy Organs had adopted milestone decisions in 2015 and 2016 on financing of the AU and the revitalization of the AU Peace Fund. Accordingly, the A3 were called upon to champion the financing of AU led peace support operations. This paved the way for the adoption of resolution 2320 (2016), facilitated by Senegal, which stressed ‘the need to enhance the predictability, sustainability and flexibility of financing for African Union-led peace support operations authorized by the Security Council.’ The subsequent resolution 2378 (2017), whose adoption was facilitated by Ethiopia, expressed the UNSC’s intention to consider partially funding AU-led peace support operations authorized by the Council through UN-assessed contributions ‘on a case-by-case basis.’

One of the factors for the delay in adopting the common position related to the factors that impeded progress in the UNSC. In 2018, Cote D’Ivoire, Equatorial Guinea and Ethiopia proposed a joint draft resolution which tried to secure a clear commitment from the Council to decide in principle to finance AU led peace support operations. The draft text had received wider support within the UNSC and the broader UN membership. However, the US under Trump administration was not willing and ready to accommodate the AU request and, in fact, threatened to exercise its veto power if the African members decide to go ahead and table the draft text for a vote.

With the Biden administration in the US and its renewed multilateral engagement, there appears to be a new window of opportunity to revive the financing issue. Both Chairperson Moussa Faki and UNSG Antonio Guterres are also expected to exert reinvigorated efforts to enhance the AU-UN partnership in their new mandate by, among others, ensuring progress on the financing issue. This will certainly unleash the potential of the partnership across the whole spectrum of peace operations. Furthermore, the EU leadership seems to be much more committed and determined to enhance its partnership with the AU and may likely pull its weight behind the AU if there is readiness to resuscitate the discussion on this issue.

This said, however, it should also be understood that the discussion on this issue would not be easy. COVID-19 has had its own impact on the discussion on peacekeeping. Increasing financial pressures, among other reasons, is forcing the UN to downsize and/or draw down peacekeeping missions in recent years. Some experts are anticipating that the tendency in the future could possibly be to prioritise affordable alternatives, such as observer missions and civilian special political missions.

Even though the Biden administration could be favorably disposed to the discussion on the issue, there is a need for serious discussion to reach a shared understanding on the way forward. This necessitates engaging the Biden administration in earnest, including the state department, National Security Council and the department of defense. It is also important for the AU to engage Congress and canvass the necessary support in the House Foreign Affairs Committee and the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations building on willingness of some congressmen to support the idea of financing AU led peace support operation as part of enhancing the role of the US.

The development of a common African position is indeed a step in the right direction and it is expected to facilitate a clear decision by AU, which will then pave the way for the A3 to resuscitate the file and try to secure a concrete commitment on the issue from the UNSC. The process will definitely take time and the necessary preparatory work for laying the ground work needs to be developed. The AU Commission and the UN Secretariat need to follow up on the implementation of their Joint Declaration of 6 December 2018, and work towards making tangible progress on some of the agreed issues as they relate to the financing issue, including the full operationalisation of the peace fund, reporting, oversight and accountability.

Most importantly, there is need to learn the right lessons from the experiences of 2018 and 2019. Ensuring greater clarity on the implementation of the AU Peace fund and demonstrating concrete commitment in sharing the burden would be vital. The full operationalization of the African Standby Force would go a long way in demonstrating AU’s commitment to shoulder responsibility on matters of peace and security in Africa. It would be absolutely important that the AU common position is accompanied by a solid roadmap with clear time lines for holding consultations and mobilizing support from all the relevant interlocutors on this file while ensuring close coordination of the AU Commission, the PSC and the A3 throughout the process for having a UNSC resolution that adequately reflects the common position.

While no formal outcome is expected from tomorrow’s meeting, the PSC is expected to provide input both on what is expected to be contained in the common position and the timeline for finalising the drafting for fulfilling the request of the AU Assembly, particularly the decision of its 14th extraordinary session held on 6 December 2020.

Session on the Common African Position on the Financing of AU led Peace Support Operations through UN Assessed Contributions

Amani Africa

Date | 21 July, 2021

Tomorrow (21 July) the African Union (AU) Peace and Security Council (PSC) is scheduled to hold a session on the common African Position on the Financing of AU led peace support operations through UN assessed contributions. The Commissioner for Political Affairs, Peace and Security (PAPS), Bankole Adeoye is expected to brief the council on the progress and state of development of the common position.

The AU Assembly in its decision of its 14th extraordinary summit requested the PSC to articulate a common African position on financing peace support operations in Africa, to guide the African Members of the UN Security Council (A3) in championing and mobilizing support within the UNSC for adoption of a resolution that will enable Africa to access UN assessed contribution for peace support operations in the Continent.

It is also to be recalled that the PSC at its 881st session held in September 2019 took a view that ‘a better articulated and African owned common position’ before a draft resolution on financing of AU peace operations through UN assessed contributions is tabled for consideration by the UN Security Council (UNSC). This decision was taken against the background of issues that emerged as the A3 members of the UNSC were seeking during 2018 and 2019 to secure a UNSC resolution authorizing in principle under agreed upon conditions the use of UN assessed contributions for AU led UNSC authorized peace support operations on a case-by-case basis.

The A3 spearheaded by Ethiopia initiated a draft resolution on financing to be adopted in December 2018 under the Cote d’Ivoire Presidency of the Security Council. However, the US threatened to Veto the resolution. Following the introduction of a so- called compromise text proposed by France to accommodate the US, the vote on the A3 draft resolution was postponed (Please refer to the Amani insight on this issue). South Africa, who initially brought the issue of financing to the Security Council in its previous membership, made the issue one of the priorities of its tenure during 2019-2020. After holding consultations on the matter including a visit by the Permanent Representatives of the A3 to Washington, D.C. to engage with the United States, including the Congress, White House and the Department of State, South Africa introduced a new and slightly updated text from the initial A3 draft and the so-called compromise draft.

When the PSC finally reviewed the matter, it felt that the latest updated draft did not adequately reflect AU interests. The PSC opted for deferring the consideration of the draft text by the UNSC pending the holding of adequate consultation at the level of the AU leading towards a common position. This aims at providing greater clarity on various issues, including on the implementation of the 75/25 formula and on the operationalization of the AU Peace Fund and its role for burden sharing. The common African position elaborated by the Commission is expected to explain some of these issues in order to ensure greater understanding and consensus within the AU and help the discussion in the UNSC move forward.

During tomorrow’s session Commissioner for PAPS, Adeoye, who revived the process for the adoption of the common position, is expected to provide update to the PSC on steps taken towards the elaboration of the common position and the orientation of the common position that will be the basis for resuscitating the discussion on A3 sponsored resolution on financing AU peace operation through UN assessed contributions. The common position is expected to take stock of and build on the various efforts undertaken both at the level of the UN and the AU.

It is worth noting that the issue of predictable and reliable financing has been one of the longstanding subjects in the AU-UN relationships on peace and security in Africa. In 2008, the UN Panel led by former Italian Prime Minister Romano Prodi on the subject recommended in its report the use of United Nations-assessed funding to support United Nations- authorized African Union peacekeeping operations for a period of no longer than six months. This was further reinforced by the UN’s 2015 High Level International Panel on Peace Operations (HIPPO) Report, which recommended the use of United Nations-assessed contributions on a case-by-case basis to support Security Council-authorized African Union peace support operations including the costs associated with deployed uniformed personnel to complement funding from the AU and/or African Member States.

On the part of the AU, the Policy Organs had adopted milestone decisions in 2015 and 2016 on financing of the AU and the revitalization of the AU Peace Fund. Accordingly, the A3 were called upon to champion the financing of AU led peace support operations. This paved the way for the adoption of resolution 2320 (2016), facilitated by Senegal, which stressed ‘the need to enhance the predictability, sustainability and flexibility of financing for African Union-led peace support operations authorized by the Security Council.’ The subsequent resolution 2378 (2017), whose adoption was facilitated by Ethiopia, expressed the UNSC’s intention to consider partially funding AU-led peace support operations authorized by the Council through UN-assessed contributions ‘on a case-by-case basis.’

One of the factors for the delay in adopting the common position related to the factors that impeded progress in the UNSC. In 2018, Cote D’Ivoire, Equatorial Guinea and Ethiopia proposed a joint draft resolution which tried to secure a clear commitment from the Council to decide in principle to finance AU led peace support operations. The draft text had received wider support within the UNSC and the broader UN membership. However, the US under Trump administration was not willing and ready to accommodate the AU request and, in fact, threatened to exercise its veto power if the African members decide to go ahead and table the draft text for a vote.

With the Biden administration in the US and its renewed multilateral engagement, there appears to be a new window of opportunity to revive the financing issue. Both Chairperson Moussa Faki and UNSG Antonio Guterres are also expected to exert reinvigorated efforts to enhance the AU-UN partnership in their new mandate by, among others, ensuring progress on the financing issue. This will certainly unleash the potential of the partnership across the whole spectrum of peace operations. Furthermore, the EU leadership seems to be much more committed and determined to enhance its partnership with the AU and may likely pull its weight behind the AU if there is readiness to resuscitate the discussion on this issue.

This said, however, it should also be understood that the discussion on this issue would not be easy. COVID-19 has had its own impact on the discussion on peacekeeping. Increasing financial pressures, among other reasons, is forcing the UN to downsize and/or draw down peacekeeping missions in recent years. Some experts are anticipating that the tendency in the future could possibly be to prioritise affordable alternatives, such as observer missions and civilian special political missions.

Even though the Biden administration could be favorably disposed to the discussion on the issue, there is a need for serious discussion to reach a shared understanding on the way forward. This necessitates engaging the Biden administration in earnest, including the state department, National Security Council and the department of defense. It is also important for the AU to engage Congress and canvass the necessary support in the House Foreign Affairs Committee and the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations building on willingness of some congressmen to support the idea of financing AU led peace support operation as part of enhancing the role of the US.

The development of a common African position is indeed a step in the right direction and it is expected to facilitate a clear decision by AU, which will then pave the way for the A3 to resuscitate the file and try to secure a concrete commitment on the issue from the UNSC. The process will definitely take time and the necessary preparatory work for laying the ground work needs to be developed. The AU Commission and the UN Secretariat need to follow up on the implementation of their Joint Declaration of 6 December 2018, and work towards making tangible progress on some of the agreed issues as they relate to the financing issue, including the full operationalisation of the peace fund, reporting, oversight and accountability.

Most importantly, there is need to learn the right lessons from the experiences of 2018 and 2019. Ensuring greater clarity on the implementation of the AU Peace fund and demonstrating concrete commitment in sharing the burden would be vital. The full operationalization of the African Standby Force would go a long way in demonstrating AU’s commitment to shoulder responsibility on matters of peace and security in Africa. It would be absolutely important that the AU common position is accompanied by a solid roadmap with clear time lines for holding consultations and mobilizing support from all the relevant interlocutors on this file while ensuring close coordination of the AU Commission, the PSC and the A3 throughout the process for having a UNSC resolution that adequately reflects the common position.

While no formal outcome is expected from tomorrow’s meeting, the PSC is expected to provide input both on what is expected to be contained in the common position and the timeline for finalising the drafting for fulfilling the request of the AU Assembly, particularly the decision of its 14th extraordinary session held on 6 December 2020.

Briefing on the Implementation of the Stabilization Strategy for the Lake Chad Basin

Amani Africa

Date | 19 July, 2021

Tomorrow (19 July) African Union (AU) Peace and Security Council (PSC) will convene its 1010th session to receive briefing on the implementation of the Stabilization Strategy for the Lake Chad Basin.

Following the opening remarks of the Chairperson of the PSC, Victor Adenkunle Adeleke, the AU Commissioner for Political Affairs, Peace and Security (PAPS), Bankole Adeoye is expected to brief the council on the strategy, focusing on the contributions of the AU. The Executive Secretary of the Lake Chad Basin Commission (LCBS) and Head of the MNJTF, Mamman Nuhu is also expected to make a presentation. The Representatives of the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) and the four states of the LCBC plus Benin may also deliver statements.

While the PSC considered the last time the situation in the Lake Chad Basin in the context of its consideration of the Multinational Joint Task Force (MNJTF) at its 973rd meeting, it was during the 816th session that the PSC endorsed the Regional Strategy for the Stabilization, Recovery & Resilience of the Boko Haram-affected Areas of the Lake Chad Basin Region (RSS).

Coming not long after the second meeting of the Steering Committee of the RSS convened virtually on 29 June 2021 in which the AU Commissioner for PAPS, Executive Secretary of the LCBC, Force Commander of the MNJTF, and representatives from the Governor’s Offices took part and reviewed the 2020 progress report by the RSS Secretariat and Regional Task Force, tomorrow’s session is also expected to evaluate the state of implementation of the strategy since its inception in 2019.

The strategy, endorsed by the PSC, is the culmination of collaborative work that brought together the LCBC, affected countries and the AU based on the recognition of the need for a comprehensive approach that goes beyond military action and encompass development efforts for addressing the root causes of terrorism and violent extremism. The strategy is articulated around nine pillars and 40 strategic objectives designed to address the short, medium and long-term needs of the region towards stabilization, resilience and recovery of the affected areas. It has a five years duration divided into two phases: the first- year inception phase (2019) and the implementation phase.

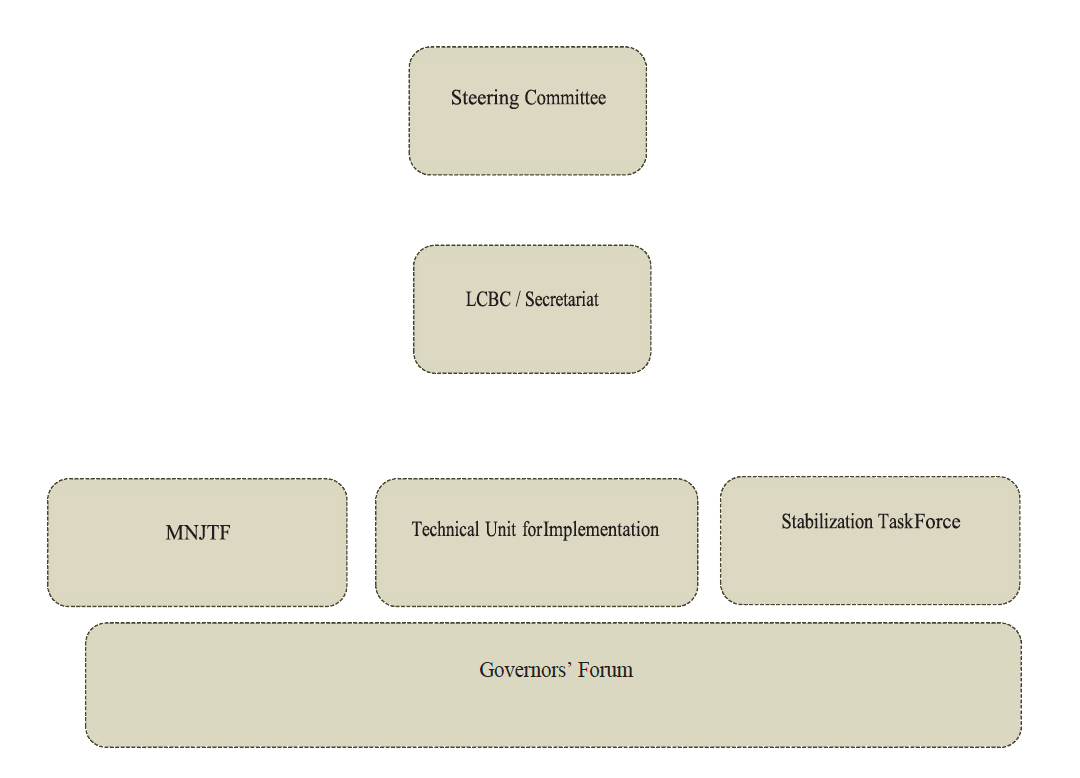

The PSC expects to receive update on the institutionalization of the RSS that set the stage for stabilization efforts to take place at territorial level, which remains the main priority of the medium and long-term implementation phase of the RSS. This includes the establishment and/or strengthening of the RSS Secretariat, the Steering Committee, the Regional Task Force, the Governors’ Forum, Civil Society platform, and the LCBC-MNJTF’s Civil- Military Cooperation (CIMIC) Cell.

The RSS Secretariat has become fully operational with the recruitment of the required staff. The development of the Regional Action Plan for the years 2020-2021, which provides strategic direction for regional actions, is now in place after its validation by the LCBC and the AU Commission last year.

The Steering Committee—a key platform for review, decision-making, and strategic direction for the RSS—held its 2nd meeting virtually on 29 June involving the participation of key stakeholders including AU Commissioner for PAPS. One of the positive outcomes of that meeting has been its decision to expand the composition of the steering committee to include relevant national authorities and entities responsible for stabilization, recovery and resilience initiatives. Relevant ministries of the four countries and the Office of the Special Coordinator for Development in the Sahel (UNISS), the African Development Bank and the Civil Society Platform are now made part of the committee. It is worth noting that the Committee is co-chaired by the LCBC and AU Commission.

The Regional Task Force, established in April 2020 and composed of technical experts appointed by organisations and entities working in the area of stabilisation, resilience, and recovery, is instrumental in enhancing the technical coordination of the pillars of intervention at the regional level. Some 30 institutions and organisations are represented in the taskforce under the leadership of the RSS Secretariat.

The establishment of RSS civil society platform is also a significant step forward. Given the critical importance of this structure for the participation of affected communities and religious and community leaders as well as women and youth and for the implementation of the RSS at the territorial level, the strength and capacity of the platform is critical.

It is also to be recalled that the Governor’s Forum was established in 2018. This platform is considered as the ‘principal custodian’ of the strategy’s implementation given its unique position to drive the implementation of the RSS at the territorial level and to coordinate joint actions of the eight affected territories of Cameroon, Chad, Nigeria and Niger. The Forum reports to the Steering Committee and advice the latter on progress of implementation of the strategy. It is to be recalled that the first and second forum were held in May 2018 (Nigeria) and July 2019 (Niger). The third edition of the meeting was supposed to take place last year in Cameroon, but rescheduled for this October due to the pandemic.

One of the major outcomes expected from the upcoming meeting of Governor’s Forum is the consideration of the Territorial Action Plans (TAPs)—comprising the set of interventions and actions tailored to local needs of the affected areas.

The development of TAPs is a critical step towards the implementation of the strategy at the territorial level, though it still awaits endorsement by the relevant authorities of the four countries before its consideration in the upcoming Governors’ Forum in October. The governors of the respective eight affected territories are responsible for preparing and harmonizing these plans with local and national development plans.

Another major step taken towards the operationalization of the RSS is the establishment of the joint LCBC-MNJTF CIMIC Cell. The CIMIC Cell serves the important role of ensuring that the planning and conduct of the MNJTF is anchored on the protection of civilians and for coordinating the activities of the MNJTF with humanitarian actors and build trust with affected communities. The Cell has played an important role in reinforcing the capacity of the MNJTF by facilitating trainings and workshops for newly deployed personnel on human rights and humanitarian law.

Of particular interest to the Council is the state of resource mobilization needed for the implementation of the strategy. It is worth noting in this regard that the UNDP supports the implementation of the strategy at national and regional levels through its funding facility, the Regional Stabilisation Facility (RSF).

In relation to specific support to the MNJTF, EU’s financial contribution of 60 million Euros (20 million through AU and the rest to be managed by EU) to support the MNJTF for 2021 is a welcome development. This is in addition to the logistical support including Air Mobility Service, Command- Control-Communication and Information System service, as well as covering allowances and salaries to civilian staff of the joint force. While this logistical support will have great importance in addressing some of the capability gaps of the joint force, other capability gaps such as Counter Improvised Explosive Devices (C-IED) equipment, counter drone equipment, and Surveillance Reconnaissance (ISR) services are yet to be filled.

In terms of challenges, such participative structures as the private sector investment platform and inter parliamentary forum are yet to be realized. Additionally, given the cross-border nature and complex structures and mechanisms of the strategy, another challenge is coordination of the plethora of stakeholders involved in security, humanitarian, stabilization, and development efforts across regional, national and territorial levels. There is also the coordination issue between the LCBC and the G5 Sahel with the overlapping membership in case of Niger and Chad.

The other challenge is the volatile security situation of the affected areas. For example, in Borno State of Nigeria, one of the eight targeted territories for the implementation of the RSS, 19 percent of the territory remains ‘either totally or mainly inaccessible to both state and humanitarian actors because of insecurity’. Security challenge is also one factor hindering cross- border interactions in the sub-region.

There is also the issue of the dominance of the MNJTF and national security troops as the principal instruments of the regional and national strategies in the region. The result is that much of the resources are diverted to security responses. Given that the member states of LCBC are primarily responsible for the implementation of the RSS, the latter’s success largely depends on the political will of member states.

The expected outcome is a communique. The Council may underscore the centrality of the implementation of the RSS in addressing the crisis caused by Boko Haram insurgency. Regarding the progress in the implementation of the strategy, the PSC is likely to express its satisfaction over the successful operationalization of the strategy with the establishment of governance and coordination structures, and may call for expediting the establishment of remaining structures. The Council is also likely to welcome the development of the Regional Action plan for 2020-2021 as well as the TAPs, and may encourage stakeholders to align their engagements in accordance with these plans. The Council may stress that the success of the strategy requires a sustained financial, technical and political support and collaboration at all levels, and it may particularly emphasize the imperative of national ownership and political will towards the implementation of the strategy. The PSC may also invite the utilization of AU’s Post Conflict Reconstruction and Development Centre to support the implementation of the strategy, including through supporting the financing and implementation of quick impact projects identified by the affected countries and the various structures of the RSS. On the challenges, the Council is expected to urge the multiple actors involved at regional, national and local level to harmonize and coordinate their actions across the development, peace and security spectrum with the view to minimize duplication of efforts and maximize their contribution towards the full realization of the strategy. The Council is also expected to express its grave concern over the continued security threat imposed by Boko Haram and its splinter, the Islamic State in West Africa Province (ISWAP) and its implication on the implementation of the RSS despite gains achieved by the MNJTF. In this regard, the Council may call on troop-contributing countries to strengthen their collaboration, and further urge the AU, EU and other partners to step up their financial and logistical support in order to sustain and enhance the capability of the multinational force.

Status report on the full operationalization of ASF and CLB

Amani Africa

Date | 08 July, 2021

Tomorrow (08 July) the African Union (AU) Peace and Security Council (PSC) is expected to convene a session to consider report of the Chairperson of the AU Commission on the full operationalisation of the Africa Standby Force (ASF) and the AU Continental Logistics Base (CLB). The convening of this session under Nigeria’s chairship of the PSC is indicative of the importance that Nigeria attaches to and draws on its earlier engagements for achieving the utilization of the ASF in deploying PSOs.

Following the opening remarks of the Chairperson of the PSC for July, Victor Adekunle Adeleke, the AU Commissioner for Political Affairs and Peace and Security, Bankole Adeoye, is expected to make a statement. The PSOD and the Chief of Staff of the ASF may also provide update to the Council. Council may also receive briefing from representatives of Regional Economic Communities/Regional Mechanisms (RECs/RMs) on the status of their respective Regional Standby Forces.

It is to be recalled that the ASF was declared to be fully operational by the AU Assembly at its 14th Extra Ordinary Session convened in December 2020. The Assembly in this decision directed the PSC to utilise the framework in mandating and authorizing AU peace support operations (PSOs). At the strategic and political levels, an issue worth addressing for the deployment of PSOs using the ASF is agreement between Member States, the REC/RMs and the AU on the processes from mandating deployment to the identification and preparation of the capabilities by RECs/RMs and the release by Member States of the capabilities they pledged as part of the regional standby force and the actual deployment of the forces to the theatre of operation.

At the institutional levels, there is also the issue of clarity on the role of strategic level ASF planning element at the level of the AU and staffing capacity of the AU ASF planning element. In this regard, the PSC may wish to discuss how its decision authorizing or mandating the deployment of a PSO is followed up by the AU ASF planning element for implementation in coordination with RECs/RMs.

One of the challenges in the utilisation of the ASF framework for mandating and authorising AU PSOs is the lack of clarity between the AU and RECs/RMs regarding the command and control of regional forces. Since the first ASF exercise in 2010, one of the outstanding questions is the respective roles of the AU and the RECs/RMs in the decision-making process for the deployment of the ASF. At Council’s first joint- consultative meeting with RECs/RMs which was convened on 24 May 2019, it was agreed that RECs/RMs shall forward to the PSC, proposals for a practical way forward in relation with the deployment of ASF.

Although the drafting of the Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) between the AU and RECs/RMs on the ASF replacing the 2008 MoU has been finalized, the MoU has as yet to be signed by the AU Commission and RECs/RMs. This MoU is expected to clarify the respective roles of the AU and RECs/RMs in mandating and deploying ASF. In tomorrow’s session, this is one of the issues in respect of which Member States of the PSC may seek clarity on what needs to be done for the signing of the MoU by the AU and the RECs/RMs.

The session also presents the opportunity for Council to be updated on the status of readiness of Regional Standby Forces. As noted by Council at its 767th session, the different RECs/RMs have shown progress in operationalising their respective standby forces. While the East African Standby Force (EASF), the Economic Community of Central African States (ECCAS), the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) and the Southern African Development Community (SADC) seem to continue taking advances, the North Africa Regional Capability (NARC) still lags behind.

Accordingly, one of the issues necessary to address is the standardization of the state of readiness of the various Standby Forces which is also critical for interoperability. While efforts have been made in developing standard for verifying the pledged capabilities of the various regional standby forces, the verification of pledged capabilities has as yet to get the buy in of the RECs/RMs.

It may also interest Council to reflect on the importance of updating the ASF to effectively respond to new and emerging threats in the continent. This principally includes the increasing proliferation of terrorism and extremist violence, outbreak and spread of health pandemics including Ebola and Covid-19, as well as natural disasters and humanitarian crises, such as climate change induced insecurity and the growing rate of forced displacement. With respect to responding to the threat of terrorism and violent extremism within the framework of ASF, it is to be recalled that Council convened a session on the establishment of a special unit on counter- terrorism within the framework of ASF at its 960th meeting. At the session, the AU Commission was requested to provide technical guidance and submit concreate proposals on the technical aspects regarding establishment of this special unit and to seek inputs from the Specialized Technical Committee on Defence, Safety and Security (STCDSS) in this regard.

Tomorrow’s session will also discuss the status of the CLB. The CLB which is based in Douala, Cameroon and forms part of the setup of the ASF serves the main purpose of ensuring the presence of policies and procedures for procuring, delivering and accounting for necessary support to all military, police and civilian components of AU PSOs. It is to be recalled that the CLB was inaugurated on 05 January 2018, by the AU Commissioner for Peace and Security and the Prime Minister of Cameroon. The update on the CLB is expected to cover staffing, use of the resources stored at the CLB, relationship of the CLB with regional logistic bases and infrastructure development including addressing the challenge of safe storage materials that partners donated and currently housed at the CLB.

As highlighted in the report of the Chairperson of the AU Commission submitted at the 13th Ordinary Meeting of African Chiefs of Defence Staff and Heads of Safety and Security and the 12th Ordinary Meeting of the STCDSS, there is need to ensure storage and security of the CLB. Moreover, the need for Member States to support the CLB through the secondment of personnel at their own cost was emphasised at the 13th Ordinary Meeting of the STCDSS. During tomorrow’s session, it is expected that the PSC will receive update on the measures taken for the safe keeping and storage of equipment that partners including Turkey and China donated. With respect to staffing, the Chairperson’s report for the session highlights that as of 9 April 2021 nine (9) military officers are deployed at the CLB seconded at own cost by AU Member States namely; Cameroon (7), Niger (1) and Morocco (1) and Nigeria (1). It also indicates that one (1) training officer from Zambia is expected to deploy soon.

The other issue expected to be discussed in relation to the CLB is the distribution from the current stock of supplies to the regional logistics bases and the use of the supplies for purposes of supporting ongoing missions. As highlighted in the Chairperson’s report, the 13th meeting of the STCDSS meeting held in November 2020 urged RECs/RMs and /or identified Member States to commit to receive and preposition ASF equipment in their Regional Logistics Depots (RLD) to facilitate future rapid deployment. It is indicated that the various RECs/RMs are at various stages in the identification and establishment of RLD with NARC, ECOWAS and EASF having RLD at various stages of operationalization and ECCAS and SADC being at stage of identification of sites for establishing respective RLD.

The expected outcome of the session is a communiqué. The PSC is expected to outline concrete steps in the process of fully operationalising and deploying the ASF and properly utilising the framework for planning and rapid deployment of PSOs to conflicts and crises in Africa. It may follow up on the proposals it requested to be submitted by RECs/RMs for a practical way forward in relation with the deployment of ASF, at its first annual joint consultative meeting with RECs/RMs. It may also call for enhancing the capacity of the ASF Planning Element at the AU. With respect to the status of signature of the 2018 MoU between AU and RECs/RMs on ASF, the PSC may call for immediate steps being taken for finalization of the signing of the MoU. In terms of the CLB, the PSC may call on RECs/RMs to work closely with the AU to speed up the establishment and operationalization of respective RLD and start receiving equipment from the CLB as part of the effort to prevent equipment from deterioration due to storage issues and lack of use. Council may commend Member States’ efforts made towards supporting the capacity of the CLB by seconding staff at their own cost and call for permanent solution for the staffing of the CLB through approved structure and budget.