Africa at a Crossroads: Pan-Africanism, Global Disorder and Collective Security

Africa at a Crossroads: Pan-Africanism, Global Disorder and Collective Security

Date | 27 February 2026

El-Ghassim Wane

Africa today faces not simply a difficult moment, but a structural turning point. The issue is not whether the world is becoming more unstable and messy — it clearly is. The real question is: What does a disorderly world mean for African security?

My core argument is straightforward: The erosion of the global order is transforming Pan-Africanism from a political aspiration into a security imperative.

Let me start with few remarks on the changing global environment and why this matters specifically for Africa.

Many of the trends now worrying the world are not new to Africans and to the Global South more broadly. For decades, stakeholders in the Global South warned about selective application of international law, unilateral action, and power politics.

For Africa, this carries a host of consequences.

First, frequent violations of international law and the increasing use of coercion, including force, in pursuit of national interests affect all states, but weaker states are affected more severely. African countries depend disproportionately on rules because they lack comparable hard power. When rules weaken, their vulnerability increases.

Second, while the current multilateral system is imperfect and unbalanced — and was designed with very little African input — it has nonetheless provided some clear advantages: coalition-building, forums to address global challenges, mediation frameworks, peacekeeping operations. As multilateralism weakens, Africa loses diplomatic leverage to advance its interests and conflict-management tools simultaneously.

Third, declining external support is not just a development issue. It is a security issue. Peace operations, DDR programmes, elections support, humanitarian assistance and even state administration in some fragile states have depended heavily on external financing.

Fourth, with heightened geopolitical competition inside Africa, the continent’s conflicts are becoming increasingly internationalized (see also here). External actors increasingly shape battlefield dynamics, while African institutions struggle to influence outcomes.

Clearly, Africa is entering a period in which it is more exposed to instability while simultaneously losing the external mechanisms that had so far contributed to manage instability. In other words, the trends described earlier do not merely create a more dangerous world — they remove the external pillars that helped African mechanisms function.

It is important here to keep in mind that Africa’s conflict management system was designed as part of a cooperative international security framework — one only needs to look at the provisions of the Peace and Security Council Protocol, especially those concerning its relationship with the United Nations and other international partners. That framework is now less predictable, less available and, in some cases, internally divided.

This raises an important question: Can African institutions maintain stability if external stabilisers become inconsistent or absent? That is the crossroads Africa is now approaching — not a philosophical choice about Pan-Africanism, but a practical challenge of collective security.

Pan-Africanism has often been treated as history, memory, or political sentiment. Today it is becoming a functional necessity. In many ways, this vindicates Kwame Nkrumah. In the early 1960s, he argued that unity was not primarily ideological — it was a condition for sovereignty in an unequal international system.

Howard French, the author of the book Born in Blackness: Africa, Africans, and the Making of the Modern World, 1471 to the Second World War and of the more recent book The Second Emancipation: Nkrumah, Pan-Africanism, and Global Blackness at High Tide, captures this well. He writes: ‘With no one in the world serving up favors to the continent, Nkrumah’s insight about the gains to be had through federation is as salient as ever. What is lacking is sufficient action. The time has come for a continent cut loose in the world to take the next step.’

And this is precisely the issue. At the very moment when the international environment is becoming more hostile, African states are not acting with the level of collective cohesion that the situation requires. And more broadly, we see a weakening reflex of continental solidarity.

The result is predictable: fragmented bargaining power, unequal deals, and diminished leverage (see also here). In peace and security, this situation also complicates the search for lasting solutions that require engagement within a coherent continental framework.

Against this backdrop, what collective security actually requires in practice?

The starting point is simple: unity is no longer an emotional or rhetorical ideal. It is strategic necessity. It determines the continent’s negotiating power, its ability to manage conflicts, and ultimately its political survival in a more competitive international environment.

So what does that mean concretely for African countries?

First, it entails deepening our collective investment in the institutions we have created. Our leaders cannot be more present at summits with external partners than at AU meetings. That sends a message — to others and to ourselves. As Désiré Assogbavi recently remarked, ‘As the world order shifts, summits in foreign capitals make the continent look like a guest at its own table.’

Second, it means cooperating fully with African conflict-management institutions. Africa already has one of the most elaborate peace and security architectures in the world: norms, institutions and expertise exist. The PSC Protocol is explicit — Member States are expected to support and cooperate with African efforts to resolve conflicts. This does not mean excluding external partners. Our crises are connected to global dynamics. But external support must reinforce African leadership, not replace it.

Third, it means honoring a commitment our leaders themselves made at the launch of the Peace and Security Council in May 2004: No African conflict should be ‘out of bounds’ for the AU, and when grave abuses occur ‘Africa should be the first to speak and the first to act.’ If we do not act when crises unfold on the continent, we should not be surprised when others step in.

Fourth, collective security does not mean isolation. It requires close partnership with the United Nations and other international stakeholders. Already in 1990, Salim Ahmed Salim, then OAU Secretary-General, argued that while Africa must strengthen its ‘inner strength’, it should continue to prioritize the UN as the principal multilateral forum through which it defends its interests internationally. That remains true today. Africa should be at the forefront of efforts to reinforce the UN and make it more fit for purpose.

Finally, collective security is also a question of responsibility. Everyone in the AU ecosystem — governments, institutions, and officials — must recognize the seriousness of the moment. Africa is entering a more demanding international environment. Routine approaches will not suffice (see here). This period requires commitment, discipline and steadfastness.

How, then, do we operationalize this ambition? What role should the AU Commission play in moving it forward ?

Stronger political commitment will clearly be required. At present, the level of collective resolve does not fully match the demands of the moment. This is a reality we must acknowledge.

But paradoxically, this makes the role of the AU Commission — which is not only an administrative body (the Constitutive Act, the PSC Protocol and several other instruments are clear in this respect) — more important, not less. Political will does not simply appear. It has to be generated, encouraged, nurtured.

In periods of geopolitical transition, tensions among Member States and inward-looking approaches as countries focus primarily on their domestic challenges, institutions matter more than ever. The Commission must act as the engine of collective action. It must engage proactively, build coalitions around sensitive issues, and create the conditions in which states feel both empowered and compelled to act.

To conclude, the world is becoming more dangerous and less structured. For Africa, the consequence is clear: external stabilizers are weakening at a time of rising internal vulnerabilities. Therefore, the question before us is not ideological. It is whether African states will face insecurity individually or manage it collectively.

Pan-Africanism, in this context, is about survival and agency. Africa can either become an arena where global competition plays out or an organized actor capable of shaping its own security environment. The decisions taken in the period ahead will determine which of the two it becomes.

Informal Consultation with Member States in Political Transition

Informal Consultation with Member States in Political Transition

Date | 26 February 2026

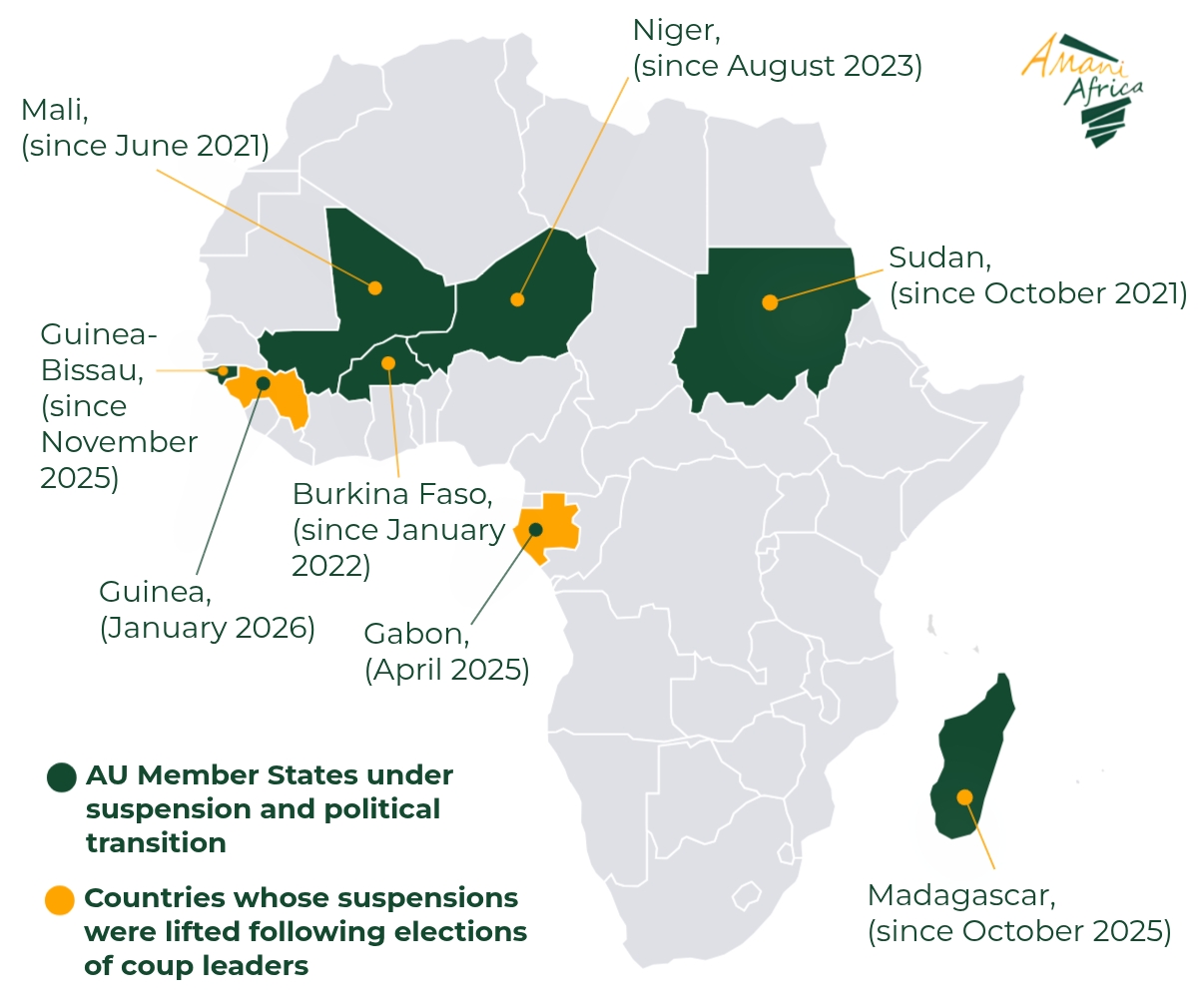

Tomorrow (27 February), the African Union (AU) Peace and Security Council (PSC) will hold an informal consultation with countries in political transition—namely Burkina Faso, Guinea-Bissau, Madagascar, Mali, Niger and Sudan.

This meeting will be the latest in the PSC’s series of informal consultations, introduced into its working methods in April 2023 following the 14th Retreat on Working Methods in November 2022. Grounded in Article 8(11) of the PSC Protocol, the mechanism enables direct engagement with representatives of Member States suspended from AU activities due to unconstitutional changes of government (UCG). Tomorrow’s session is expected to take stock of progress and outstanding challenges since the late 2025 consultation, in light of evolving regional dynamics.

The PSC scheduled an informal consultation on Sudan early in the month, with Sudan ahead of the PSC ministerial session held on 12 February 2026 on the situation in Sudan. While there is no public record of whether the PSC held such an informal consultation, the Foreign Minister of Sudan was present and made a statement at the opening segment of the 1330th meeting of the PSC dedicated to the situations in Sudan and Somalia.

Two notable developments are notable in relation to countries in transition. First, military coups in Guinea-Bissau and Madagascar have kept the number of states under suspension unchanged despite the lifting of the suspension of Gabon. Second was the lifting of Guinea’s suspension from the AU, notwithstanding concerns regarding compliance with Article 25(4) of the African Charter on Democracy, Elections and Governance (ACDEG), which renders perpetrators of UCG ineligible to contest elections organised to restore constitutional order. At its 1325th meeting on 22 January 2026, the PSC determined that the political transition in Guinea had culminated in ‘the successful organisation of the presidential election on 28 December 2025’ and consequently lifted the suspension. Yet, this step did not change the number of states under suspension in 2026 from the number in 2024.

What was problematic with respect to the decision to lift suspension of Gabon and Guinea, thereby endorsing the legitimisation of coup makers through election, was not simply PSC’s lack of consideration of Article 25(4) of ACDEG. It was rather the PSC’s repeated inability to explicitly state that the provision of the AU norm on non-eligibility of those who participated in unconstitutional changes of government for elections organised for restoring constitutional order remains part of the AU anti-coup norm, and it stands by that provision. This issue took the spotlight during the 39th Ordinary Session of the AU Assembly when the Chairperson of the AU, Angola’s President Jõao Manuel Lourenço, during the opening session of the Assembly in his address, pointed out.

While informal consultations have now become regularized as a format of PSC meeting, it remains far from clear that their potential and value is adequately explored. One issue with the informal consultations is how to use them beyond just being a platform for the exchange of information. The critical test for the value of the informal exchange is whether it facilitates improved understanding and relationship between the AU and the countries in transition, and how the insights gleaned from the consultations help to improve and advance a more effective AU policy engagement in the countries in transition.

What additionally limits the value of the informal consultation in its current design is the fact that it does not afford tailored discussion on the specificities of each country’s situation. The transitional dynamics of the different countries are unique to each and deserve dedicated attention for advancing a more effective policy reflective of and responsive to the needs of each. Best practice from the UN Security Council suggests that, unless it is for thematic issues, country situations are dealt with individually, even in informal meetings. In this respect, the inclusion in the program of work for February 2026 of an informal consultation dedicated to Sudan sets a good example in taking the use of informal consultations to the next level.

Another challenge, not unrelated to the above, witnessed during 2025 was the lack of participation on the part of representatives of some of the member states to engage in some of the informal consultations. For example, it was the lack of confirmation of participation by the representatives of some of the member states that led to the cancellation of the planned informal consultation in November 2025. Tomorrow’s informal consultation provides an opportunity for taking stock of what worked and how to improve this engagement for enhancing effective policy engagement of the AU in support of both implementation of reform processes for transition and efforts towards achieving peace in Sudan and containing the terrorist menace in Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger.

During tomorrow’s informal consultation, representatives of the affected countries are expected to provide an update on the transitional process of each of their respective countries.

As noted in the analysis in the Insight for the December 2025 informal consultations, a central challenge in relation to the AES is how the AU and ECOWAS can integrate the restoration of constitutional order into a broader stabilisation and state authority expansion strategy, supported by a jointly developed and deployed security mechanism. These concerns resonate with warnings issued at the UN Security Council meeting last November, where ECOWAS Commission President Omar Alieu Touray described terrorism as an ‘existential threat’ to West Africa, while President Julius Maada Bio, Sierra Leone’s President, Chair of ECOWAS and UNSC President for November, outlined the need for engaging directly with Sahel states, rebuilding trust, and supporting nationally owned transitional processes. Stating that the time is ‘for bold and coordinated action,’ he proposed an ECOWAS-AU-UN compact for peace and resilience in the Sahel as an instrument for addressing the grave situation facing the Sahel and viewing the AES not as an adversary but as a partner that can complement ECOWAS and AU. The informal consultation may serve as an opportunity to discuss with AES states for taking these outlines forward.

In relation to Madagascar, tomorrow’s informal consultation will present an opportunity to hear from the representative of Madagascar on the progress made in the development of a transitional roadmap and the inclusivity of the process for elaborating the roadmap. Madagascar had earlier launched a National Consultation on 10 December 2025 to advance constitutional reform toward a Fifth Republic through a six-month, inclusive, nationwide process. It may additionally consider how the AU, working in close coordination with SADC, in accordance with the communiqué of its 1313th meeting on 20 November, can enhance its engagement for ensuring that the reforms necessary for preventing the recurrence of coups in Madagascar are crafted and implemented as part of the transitional process. The consultation may thus additionally consider how the AU, working in close coordination with SADC, in accordance with the communiqué of its 1313th meeting on 20 November, can enhance its engagement for ensuring that the reforms necessary for preventing the recurrence of coups in Madagascar are crafted and implemented as part of the transitional process.

With respect to Guinea-Bissau, the consultation is expected to assess the extent to which steps taken by the military junta towards creating inclusive political conditions towards the development of a transitional roadmap for the restoration of constitutional order. It is expected that the representative of Guinea-Bissau will provide an update on the steps taken. These may include the formation of a transition government, the allocation of three ministerial posts each to the African Party for the Independence of Guinea and Cape Verde and the political group led by Fernando Dias Da Costa (the leading candidate in the November election), the appointment of 10 representatives from the two blocs to the National Transition Council, the release of political prisoner and the withdrawal of the request for the departure of the ECOWAS Stabilization Support Mission. However, it is worth noting that opposition leaders decline participation. Subsequently, the transitional authorities announced that legislative and presidential elections would be held on 6 December 2026, with Horta Inta-a asserting that ‘all the conditions for organising free, fair and transparent elections have been met.’ Given that the transitional charter issued in early December barred him from contesting the polls, the PSC members may use the opportunity of the informal consultation to applaud this step as a measure that ensures compliance with Article 24(5) of the ACDEG and urge its compliance.

On Sudan, there has been no major development since the PSC meeting of 12 February as far as the transitional process is concerned. Tomorrow’s informal consultation, however, will afford the representative of Sudan to reflect on the outcome of the PSC ministerial session on Sudan held early in the month.

Similar to prior consultations, tomorrow’s session is not anticipated to produce an outcome document.

2026 Election of the 10 Members of the PSC: Rejuvenation or Continuing Decline?

2026 Election of the 10 Members of the PSC: Rejuvenation or Continuing Decline?

Date | 24 February 2026

INTRODUCTION

The 2026 election for the 10 members of the African Union (AU) Peace and Security Council (PSC) was held by the Executive Council on 11 February 2026 at its 48th Ordinary session, in line with the power vested in it pursuant to Decision Assembly/AU/Dec.106 (VI) of the Sixth Ordinary Session of the Assembly. The outcome of the election was endorsed by the Assembly during its 39th ordinary session on 14 and 15 February. The result of the election produced a significant change in the composition of the PSC, bringing to the PSC more than 1/3 new members, including Morocco and South Africa.

In a notable development, Somalia became the latest AU member state to be elected to the PSC for the first time, after three earlier unsuccessful attempts. Also notable was the large number of withdrawals between the closing of the submission of candidacy and the day of the election. The number of candidates shrank by nine (9) at the time of voting. As a result, there were only two AU regions (North Africa and Southern Africa) that had a list of candidates that was in excess of the number of seats available.

This policy brief provides an analysis of the conduct and outcome of the elections. It also highlights the key dynamics that transpired in the lead-up to and during the election, as well as the ways in which the new composition of membership would affect the PSC between rejuvenation and persisting decline in effectiveness and impact.

Consultation meeting with FAO, WFP, and IFAD on the nexus between Food, Peace, and Security

Consultation meeting with FAO, WFP, and IFAD on the nexus between Food, Peace, and Security

Date | 23 February 2026

Tomorrow (24 February), the African Union (AU) Peace and Security Council (PSC) is expected to convene its 1332nd meeting with the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), the World Food Programme (WFP), and the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD) on the nexus between Food, Peace, and Security.

The session will commence with an opening statement from Obeida A. El Dandarawy, Permanent Representative of the Arab Republic of Egypt to the AU and Chairperson of the PSC for February, followed by introductory remarks by Bankole Adeoye, AU Commissioner for Political Affairs, Peace and Security. It is expected that Moses Vilakati, AU Commissioner for Agriculture, Rural Development, Blue Economy and Sustainable Development will make a statement. The representatives of FAO, WFP and IFAD will also be expected to make their respective presentations.

The PSC had last scheduled a similar agenda item on its programme for May 2025. However, the session did not happen as planned. In 2017, during its 660th and 708th sessions, the PSC framed drought and food shortages as drivers of instability. It warned that climate-driven droughts are ‘major triggers of tensions and violence in communities.’ However, the PSC did not hold a session dedicated directly to food insecurity and conflict nexus until 2022. This changed at its 1083rd session, when the Council held a session fully dedicated to ‘Food Security and Conflict in Africa,’ as part of the 2022 AU theme on nutrition and food security. Later in 2022, the PSC again took up food security in the context of climate change. As highlighted in the communiqué of the 1083ʳᵈ session of the PSC, one of the ways that armed conflicts contribute to food insecurity is by severely disrupting agriculture and food systems. Later on in July 2025, this issue received attention during the PSC’s 1286th meeting on the ‘Humanitarian Situation in Africa,’ where it underscored ‘the importance of adopting a holistic strategy in food systems that addresses both production and consumption, focusing on sustainability, resilience, and equity.’ In this regard, it called for the ‘implementation of an African renaissance in agri-food systems approach and the Comprehensive Africa Agriculture Development Program (CAADP) Kampala Declaration.’ This is where, during tomorrow’s session, the engagement with FAO and IFAD can highlight how their interventions can build on and leverage CAADP and the CACDP Kampala Declaration to advance early planning and intervention.

In July 2025, Addis Ababa co-hosted the 2nd United Nations Food Systems Summit Stocktake (UNFSS+4) building on the momentum of the 2021 UN Food Systems Summit (UNFSS) and the first Stocktake in 2023 (UNFSS+2) to reflect on global progress in food systems transformation, strengthen collaboration, and unlock finance and investments to accelerate action towards the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The Summit saw the launch of the State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2025 (SOFI) report, which revealed a modest decline in global hunger – but a troubling rise in food insecurity in Africa. The report highlighted how persistent food price inflation has undermined access to healthy diets, especially for low-income populations, calling for coherent fiscal and monetary policies to stabilise markets, emphasising the need for governments and central banks to act in alignment. It also called for open and resilient trade systems to ensure the steady flow of goods across borders. Additionally, it urged the implementation of targeted social protection measures to support at-risk populations most vulnerable to economic shocks, and also stressed the importance of sustained investment in resilient agrifood systems to strengthen food security and long-term stability. In this context, care should be taken to ensure that short-term interventions do not compromise African biodiversity in sources of food, thereby undermining long-term food security.

Food insecurity remains prevalent in various parts of the continent, with conflict settings hit particularly hard. According to the globally recognised Integrated Food Security Phase Classification (IPC)—a standard tool for assessing food insecurity severity—more than two-thirds of African countries are currently classified as IPC Phase 3 (Crisis) or higher. Since the PSC’s last session dedicated to this agenda, various cases on the continent have come to show that food insecurity is accelerating, exacerbated mostly by conflict and insecurity. The nexus between food insecurity and armed conflict reinforces each other in a vicious cycle. On the one hand, conflict is a primary driver of hunger, as violence displaces farmers, destroys crops and infrastructure, and disrupts supply chains. Conflict and insecurity also exacerbate food insecurity by impeding response and humanitarian access, including the use of humanitarian access as a weapon of war.

One conflict situation that aptly illustrates the deadly interface between food insecurity and conflicts in which humanitarian access is used as a weapon of war is in Sudan. The intensification of the war and notably the weaponisation of humanitarian access, particularly by the RSF, has culminated in ‘the world’s worst famine.’ Beyond Zamzam camp and neighbouring areas in North Darfur, the UN’s IPC latest report established that levels of acute malnutrition have surpassed famine thresholds in two other areas in North Darfur, Um Baru and Kernoi. This means that Sudan possesses a new humanitarian record of having ‘the most areas of active famine on the planet.’ Altogether, according to WFP, an estimated 834,000 people in the region are experiencing famine, representing over 40 per cent of the global famine caseload.

Food crises categorised as IPC Phase 3 and above are no longer limited to conflict-affected states. Through WFP, it has been reported that the latest analysis from the Cadre Harmonisé – the equivalent of the IPC for West and Central Africa – also projects that over three million people will face emergency levels of food insecurity (Phase 4) this year – more than double the 1.5 million in 2020. Four countries – Nigeria, Chad, Cameroon, and Niger- account for 77 per cent of the food insecurity figures, including 15,000 people in Nigeria’s Borno State at risk of catastrophic hunger (IPC-5) for the first time in nearly a decade. While these conditions are accelerated by insecurity, they also contribute to the aggravation of insecurity.

The ‘WFP 2025 Global Outlook’ highlighted that the Eastern Africa region faces compounded crises driven by conflicts, widespread displacement and climate shocks, leaving nearly 62 million people acutely food insecure. The region grapples with more than 26 million displaced people, with Sudan representing the largest crisis globally at 11.3 million. In Sudan, in addition to the Zamzam, 13 additional areas with a high presence of IDPs and refugees are at risk of famine.

FAO’s ‘State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2025’ paints similar pictures as the other reports. Among the African countries with the largest numbers of people facing high levels of acute food insecurity were Nigeria, Sudan, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) and Ethiopia, while the countries with the largest share of the analysed population facing high levels of acute food insecurity were Sudan and South Sudan, among others globally. More than half of the people living in South Sudan and the Sudan faced high levels of acute food insecurity. While it is not the only factor that accounts for these conditions of food insecurity in these countries, in all of them, conflict and insecurity constitute a significant contributor and factor.

Increasingly, relatively stable countries are slipping into crisis due to economic shocks and climate change. The rising cost of living and widespread economic hardship have made food insecurity a catalyst for social unrest and political instability in various parts of the continent, including the mass protests witnessed in countries such as Sierra Leone, Tunisia, Kenya and Nigeria during 2022, 2023 and 2024, as well as Madagascar in 2025. These cases highlight that it is particularly in contexts in which there are widespread perceptions of ineffective, unresponsive, corrupt and weak systems of governance that food-related grievances spark broader political discontent and mass protests. Debt distress facing some countries and the increasing diversion of resources from key sectors like agriculture and social security also play a part in these cases. Additionally, scarcity, accelerated by climate change, raises tensions over land, water and food resources, making disputes more likely to turn violent. Competition between herders and farmers over dwindling pasturelands and fields has triggered thousands of casualties in West and Central Africa.

As part of its exploration of how to enhance ways of addressing food insecurity in conflict settings, the PSC may also consider the role of the African Peace and Security Architecture and other AU entities that play a role in humanitarian affairs. In this context, tomorrow’s session may assess progress made in the development and implementation of anticipatory tools for crisis preparedness and early action, as well as the use of humanitarian diplomacy as part of the toolbox for responding to the humanitarian dimension of conflicts in Africa, including conflict-induced food insecurity. The session may also revisit the AU’s ongoing challenge in financing humanitarian assistance and emphasise the need for Member States to fulfil their commitments, particularly the decision to increase contributions to the Refugees and IDPs Fund from 2% to 4% as outlined in EX.CL/Dec.567(XVII). Additionally, tomorrow’s session may also consider the contribution that the Africa Risk Capacity (ARC) could make. For instance, the introduction of a new parametric insurance product in 2023 to help African countries deal with flood-related impacts. Furthermore, the PSC may highlight the importance of the Special Emergency Assistance Fund (SEAF) in supporting populations affected by drought, famine, and food insecurity, while urging continued international support as a lifeline for vulnerable groups across the continent.

The expected outcome of the session could be a communiqué. The PSC may express grave concern over the worsening food security situation across Africa, particularly in conflict-affected regions such as Sudan, the DRC, and the Sahel. Council may reaffirm its condemnation of the use of starvation as a weapon of war and the deliberate targeting of food systems and humanitarian access, in breach of international humanitarian law. To build resilience, the Council may urge Member States to increase public investment in agriculture and rural development in accordance with the Malabo Declaration target of allocating 10% of national budgets to the sector. Recognising the dual role of food insecurity both as a consequence and a driver of conflict, the Council may emphasise the need to strengthen early warning mechanisms that integrate food security indicators with conflict risk assessments. It may also encourage the establishment of joint task forces that bridge peace, humanitarian, and development actors to enhance coordinated responses. Furthermore, the PSC could call for fast-tracked operationalisation and financing of the African Humanitarian Agency (AfHA) and emphasise the role of Africa Risk Capacity (ARC) and the Special Emergency Assistance Fund (SEAF) in supporting anticipatory action and crisis response. The PSC may also call for the inclusion of the explicit requirement in the mandate of mediators, special political missions and those entrusted with peacemaking to dedicate time and effort to address the crisis of food security for conflicts on which they work. Finally, in light of the burden of unsustainable debt on public budgets, inducing and exacerbating food insecurity, the Council may advocate for coordinated debt relief, reform of the international financial system, and safeguarding domestic resource mobilisation from being redirected to servicing debt at the expense of ensuring adequate investment in food systems and peacebuilding efforts.

Open Session on Climate, Peace and Security

Open Session on Climate, Peace and Security

18 February 2026

Tomorrow (19 February), the African Union (AU) Peace and Security Council (PSC) is expected to convene an open session on the ‘Nexus between Climate Change, Peace, and Security in Africa.’

The session commences with opening remarks by Obeida A. El Dandarawy, Permanent Representative of the Arab Republic of Egypt to the AU and Chairperson of the PSC for February. This is followed by an introductory remark from the AU Commissioner for Political Affairs, Peace, and Security (PAPS), Bankole Adeoye. A presentation by Moses Vilakati, AU Commissioner for Agriculture, Rural Development, Blue Economy and Sustainable Environment may also feature. In addition, statements are expected from AU Member States, representatives of the Regional Economic Communities/Regional Mechanisms (RECs/RMs), and representatives of the United Nations Office to the African Union (UNOAU).

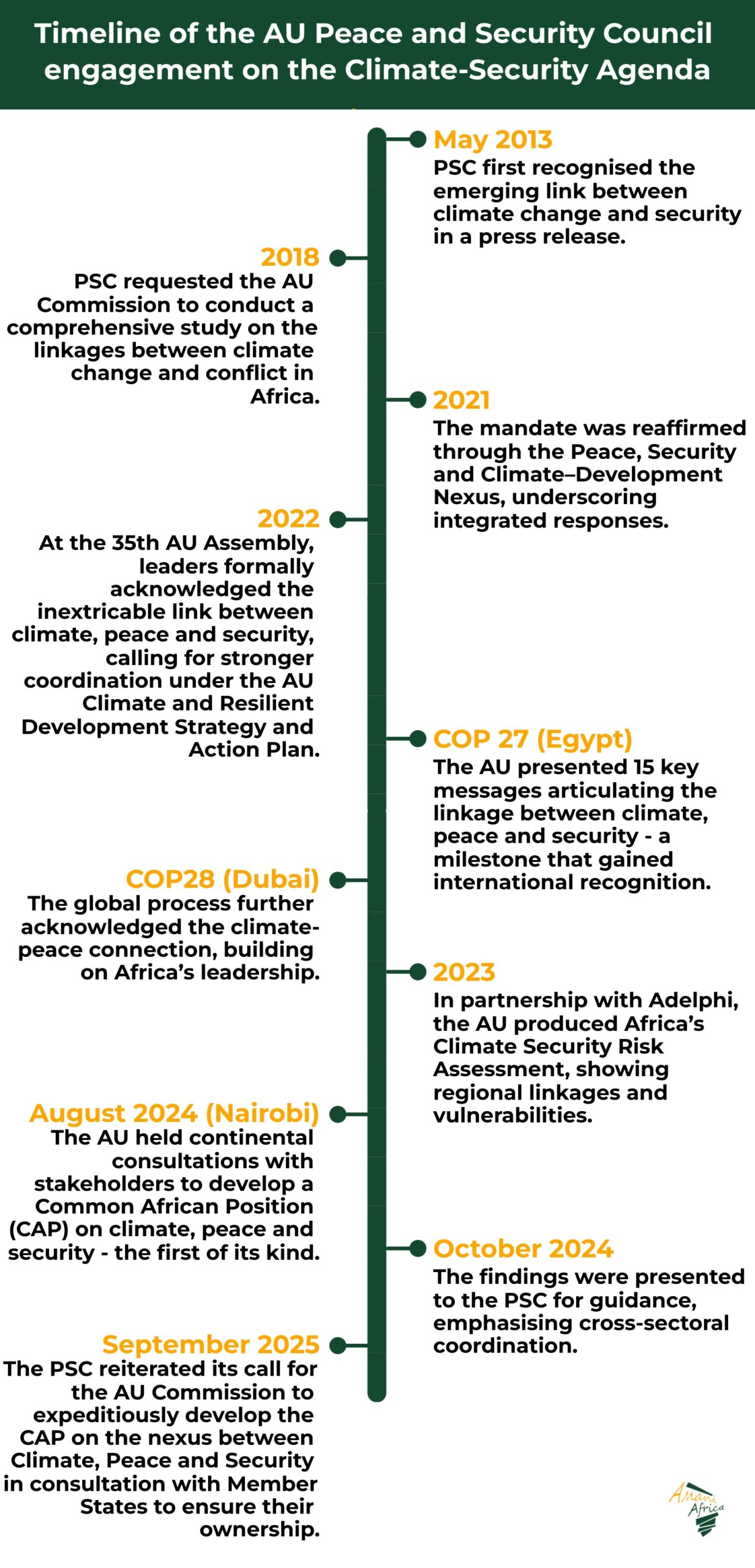

This meeting builds on the PSC’s long-standing engagement with the climate-security nexus since its 585th session in March 2016, through which the Council committed to holding annual deliberations on climate change and peace and security. In the past two years, the PSC has gone further, dedicating two sessions to the theme each year. This will mark the PSC’s 18th such session, including its 1301st Session(September 2025) and 1263rd Session(March 2025), both of which reaffirmed climate change as a risk multiplier that exacerbates political, socio-economic, and governance vulnerabilities, rather than a direct conflict trigger. Quantifying this effect, recent analysis of data from 51 African countries spanning 1960 to 2023 highlights the profound socioeconomic and political risks linked to rising temperatures. In the continent’s poorest nations, a 1°C increase is associated with a 10-percentage-point higher likelihood of exacerbating existing vulnerabilities, sometimes leading to civil conflict, whereas wealthier countries show no comparable vulnerability. Moreover, higher temperatures are linked to slower economic growth, reducing GDP growth rates by up to 4 percentage points in hotter years relative to cooler ones.

These trends are consistent with global scientific assessments, particularly findings from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), which indicate that Africa is warming faster than the global average and is experiencing increasingly frequent and intense extreme climate events, including heatwaves, droughts, floods, and cyclones. Additionally, the World Meteorological Organisation (WMO) reports that climate-related disasters in Africa have increased fivefold over the last 50 years.

The peace and security implications of the combination of political, institutional and development fragilities and tensions on the one hand and this climatic trend are stark. It is this interplay, not climate change in itself, that explains why 12 of the International Rescue Committee’s (IRC) 16 epicentres of crisis, countries marked by intertwined climate vulnerability, extreme poverty, and armed conflict, are in Africa. This underscores the need to prioritise the factors that perpetuate these vulnerabilities, account for climate impacts, and address climate change through broader policy processes.

Climate stress increasingly intersects with armed conflict, weak governance, livelihood loss and displacement, deepening instability in regions such as the Sahel, the Horn of Africa and parts of Western, Central and Southern Africa. As of early October 2025, OCHA reports that severe flooding in South Sudan had affected more than 639,000 people across 26 counties, intensifying competition over land and water already strained by drought and deepening post-conflict fragility. These climate-driven livelihood losses are fueling intercommunal violence and the growth of armed rivalries, reinforcing cycles of insecurity amid rising political tensions among rival political forces in the country.

Yet the relationship between climate and security is not one-directional. War and conflicts, as well as political instability, also contribute to making climatic stresses much more devastating. Thus, on this flip side, the ongoing conflict in Sudan has intensified the effects of prolonged drought, devastating crops and livestock, and gravely eroding livelihoods and survival capacities.

These continent-wide dynamics are increasingly manifesting in specific national contexts, where climate-induced environmental stress directly amplifies localised tensions and entrenched security threats. For instance, recent research indicates that the degradation of land and water has heightened competition between farming and pastoralist communities in Nigeria, and the research further highlights that ‘the clashes over scarce resources now claim more lives annually than the Boko Haram insurgency itself’. The caveat in this respect is that it is not merely the climate change impact in intensifying competition over resources that makes the ensuing clashes deadlier. What made climate-induced inter-communal clashes over scarce resources deadlier is their combination with the widespread availability of small arms and light weapons.

Against this background, the PSC’s previous sessions, particularly the 1301st session of September 2025, were notable for situating climate change firmly within a broader climate policy framework anchored in development, justice, and equity, focusing on loss and damage, adaptation financing, and the differentiated vulnerabilities of least-developed and conflict-affected African states. In this regard, the Council is expected to discuss the implications of anchoring climate-security responses within a broader justice-oriented framework. This includes ensuring effective implementation of COP29 commitments on adaptation, loss and damage, and associated financing.

Another dimension of the climate-security nexus relates to access to climate finance. As shown below, fragile and conflict-affected countries, which are the most vulnerable to climate change impacts, have the most need for climate finance. However, their risk profile means that they have the least access to climate finance. It is therefore of particular interest for the PSC to reflect on how access to climate finance can be expanded, paying particular attention to fragile and conflict-affected countries.

Tomorrow’s session is also expected to get an update on the work for the finalisation of the Common African Position (CAP) on Climate Change, Peace and Security. It is to be recalled that updates provided during the 1301st session indicated that the CAP is now expected to be concluded ahead of COP31, reflecting the need for input of member states, deeper consultation and alignment with existing AU frameworks, including the Africa Group of Negotiators. The delay also underscored ongoing political sensitivities, but it also highlights the strategic importance of ensuring Member State ownership and coherence across Africa’s climate and peace architectures. Since the last session and the update from Adoye, the draft CAP was presented at a technical meeting held in Nairobi, Kenya. The technical meeting held in Nairobi, Kenya on 25-27 November 2025 under the title “AU member States Validation Workshop on the Draft Common African Position on the Climate Change, peace and security nexus (CAP-CPS)’ concluded without validating the draft. The outcome statement outlined the five-step process roadmap to finalise the work.

Financing for adaptation is also expected to feature during the session. Despite being among the most climate-vulnerable regions, Africa continues to receive a disproportionately small share of global climate finance; according to the United Nations Development Programme, nearly 90% of climate funding is concentrated in high- and middle-income, high-emitting countries, while fragile states, where climate risks intersect most acutely with conflict and governance challenges, receive the least support. This imbalance is particularly stark in conflict-affected settings, where communities obtain on average only one-third of the per-capita adaptation funding available in non-conflict contexts, and countries facing protracted crises continue to receive lower levels of climate-related Official Development Assistance despite their heightened vulnerability. Against this backdrop, the PSC is likely to revisit the outcome of COP30 in Belém, where nations pledged to triple adaptation funding by 2035, a timetable that many African experts deem too slow given the continent’s acute climate vulnerabilities, and most climate finance remains loan-heavy rather than grant-based, further risking debt stress for African states. The Council is therefore expected to focus on the urgent need to honour existing commitments, reform barriers to accessing climate funds, and acknowledge that the persistent under-financing of adaptation is not merely a development challenge but an escalating driver of fragility, fiscal stress, and long-term peace and security risks across Africa that is not without global consequences.

Loss and damage is another policy issue of urgency expected to feature during tomorrow’s session. With climate-induced floods, droughts and cyclones causing repeated destruction of infrastructure, livelihoods and ecosystems, Africa continues to incur billions of dollars in losses annually. The African Development Bank estimates that climate change already costs African economies 2–5% of GDP each year, for some even reaching double digits. The PSC is thus likely to stress the need for accelerated operationalisation and capitalisation of the loss and damage fund in ways that are responsive to African realities.

Operationally, the session is expected to advance discussions on mainstreaming climate considerations into the AU’s peace and security architecture. This includes integrating climate-conflict indicators into early warning systems, strengthening preparedness and disaster risk reduction, and framing adaptation and governance as peacebuilding strategies. Notably, previous PSC sessions have recognised mobility and transhumance as legitimate adaptation strategies, calling for improved cross-border governance and regional cooperation to reduce climate-induced tensions, an approach of particular relevance to the Sahel and the Horn of Africa. Building on this evolving operational focus, the PSC is expected to articulate more concrete follow-up measures, including clearer guidance on implementing climate-security risk assessments in situations under its agenda, strengthening coordination between early warning and response mechanisms, and enhancing collaboration with regional actors to translate these policy commitments into practical preventive and resilience-building actions on the ground.

The session may also revisit the PSC’s earlier call for ensuring that climate-peace and security considerations are fully integrated into continental and global climate policy processes, including the work of CAHOSCC and Africa’s engagement in upcoming multilateral forums such as the G20 and COP31. This remains critical for ensuring that Africa’s concerns around the security dimension of climate and the requisite measures to address the security risks of climate are not marginalised in global policy processes that tend to be increasingly dominated by mitigation and market-based approaches.

The outcome of the session is expected to be a communiqué. The PSC is likely to reaffirm its longstanding position that climate change constitutes a risk multiplier that exacerbates existing political, socio-economic and governance vulnerabilities across Africa and is not a direct cause of conflicts. In this regard, the Council is expected to reiterate its call for the expedited finalisation of the Common African Position (CAP) on Climate Change, Peace and Security within this framework and stress the importance of inclusive consultations, strong Member State ownership, and coherence with existing continental frameworks and Africa’s global climate diplomacy. The PSC may also underline that climate-security engagement should complement, rather than substitute, broader climate policy processes and remain anchored in the principle of common but differentiated responsibilities and Africa’s development priorities. The Council is also expected to call for concrete steps to operationalise the mainstreaming of climate considerations into conflict prevention and peacebuilding efforts, including the integration of climate-conflict indicators into the Continental Early Warning System, the development of standardised climate-security risk assessment tools, and stronger coordination between early warning, humanitarian and response mechanisms. In addition, the PSC is expected to express concern over the widening gap between Africa’s climate needs and available financing, and call for scaled-up, predictable and accessible climate finance, particularly in grant form and with particular attention to the needs of fragile and conflict-affected states. PSC may also call for the capitalisation of the loss and damage fund and the adoption of debt suspension clauses when a country is hit by climate-induced disasters. Finally, the PSC is expected to call for enhanced coordination between the AU, Regional Economic Communities/Regional Mechanisms, Member States and international partners, and to stress the importance of ensuring that Africa’s climate-security priorities are effectively reflected in global climate negotiations and multilateral processes, including through engagement with continental mechanisms such as the Committee of African Heads of State and Government on Climate Change.

Opening Strategic Address by H.E. Mohamed El-Amine Souef Chief of Staff of the Chairperson of the African Union Commission

Opening Strategic Address

Africa at a Crossroads: Pan-Africanism, the Breakdown of the Global Order, and the Future of Collective Security Pre-AU Summit High-Level Dialogue Addis Ababa, 10 February 2026

H.E. Mohamed El-Amine Souef Chief of Staff of the Chairperson of the African Union Commission

Date | 10 February 2026

Distinguished guests, Excellencies, Dr Solomon Dersso, Director of Amani, Ladies and Gentlemen,

It is both an honour and a responsibility to address you today, on the eve of the 39th Ordinary Summit of the African Union, at a moment of profound significance for our continent and for the international system as a whole.

We meet under the theme “Africa at a Crossroads” because Africa is indeed facing a defining historical moment. The choices we make today will shape our position, our voice, and our agency for decades to come.

The global order on which Africa and the world have relied is undergoing a deep rupture. Multilateralism is under strain. Respect for international law is increasingly selective. Unilateralism, protectionism, and power politics are resurging, while geopolitical rivalries intensify. Global institutions, including the United Nations, face serious crises of legitimacy, effectiveness, and resources.

These developments are not distant from Africa. They directly affect our peace and security environment, our development prospects, and the credibility of the multilateral system on which we continue to depend.

At the same time, Africa is confronting serious internal challenges. Across the continent, violent conflicts persist and evolve, new forms of insecurity are emerging, socio-economic pressures are mounting, and democratic governance is under strain in several contexts. Of particular concern is the erosion of Pan-Africanism as a guiding political force underpinning continental solidarity, leadership, and collective responsibility.

History, however, reminds us that Africa has faced such crossroads before. At the end of the Cold War, the continent chose collective responsibility over fragmentation and transformed the Organization of African Unity into the African Union. Today, we are once again called upon to demonstrate that same resolve.

Africa can no longer afford to be a spectator in a rapidly changing world. The urgency before us is real. Our continent possesses immense strategic assets, including critical minerals essential for the global energy and digital transitions, vast economic potential, and a young and dynamic population.

Yet potential alone does not translate into influence.

dynamique dont les aspirations doivent trouver des réponses en termes d’opportunités, de dignité et d’inclusion.

Mais le potentiel seul ne suffit pas à conférer de l’influence.

Si l’Afrique reste confinée à l’exportation de matières premières et à la réaction face à des agendas définis ailleurs, elle continuera à occuper les marges des décisions mondiales, malgré sa position centrale dans leurs conséquences.

C’est précisément pourquoi l’Agenda 2063 demeure notre boussole stratégique. Sa vision d’« une Afrique intégrée, prospère et pacifique, portée par ses propres citoyens et agissant comme une force dynamique à l’échelle mondiale » parle directement à notre réalité actuelle. Reprendre cette vision exige que l’Afrique parle d’une seule voix, renforce sa cohésion et consolide ses institutions régionales et continentales.

La Zone de Libre-Échange Continentale Africaine constitue un instrument concret dans ce cadre. En renforçant le commerce intra-africain, en développant les chaînes de valeur régionales et en soutenant l’industrialisation, elle peut contribuer à transformer la richesse de l’Afrique en développement durable et en participation significative à la production mondiale à valeur ajoutée.

La paix, la sécurité et le développement sont indissociables.

Aujourd’hui, la sécurité collective doit être comprise de manière plus large et intégrée. Elle dépasse l’absence de guerre pour inclure la sécurité humaine, la souveraineté économique, la résilience climatique, la sécurité sanitaire et la stabilité institutionnelle. Dans ce contexte, la réforme de la gouvernance mondiale, en particulier du Conseil de Sécurité des Nations Unies, n’est pas symbolique pour l’Afrique. Il s’agit d’une question de légitimité, d’efficacité et d’équité. Un système qui ne reflète pas les réalités géopolitiques contemporaines ne peut assurer une paix durable.

L’Afrique, aux côtés du Sud Global, doit continuer à plaider pour un système multilatéral qui reflète le monde d’aujourd’hui, et non les configurations de pouvoir du passé.

Excellences, Mesdames et Messieurs,

L’Afrique n’est pas en retard dans le cours de l’histoire. L’Afrique est au sein de l’histoire et de plus en plus au centre. Ce qui est requis maintenant, c’est la volonté politique de s’affirmer, la clarté stratégique pour agir collectivement et le courage de passer du diagnostic à la décision.

Ce dialogue pré-sommet offre un espace opportun de réflexion et d’alignement stratégique. Utilisons-le pour réaffirmer le Pan-Africanisme comme identité politique de l’Afrique et boussole directrice, et pour tracer un chemin collectif crédible.

Sans une Afrique forte, unie et engagée, il ne peut y avoir de sécurité mondiale durable ni d’ordre mondial équitable.

Je vous remercie de votre attention et me réjouis de nos délibérations.

If Africa remains confined to exporting raw materials and reacting to agendas set elsewhere, it will remain on the margins of global decision-making, despite being at the centre of its consequences. This is why Agenda 2063 remains our strategic compass. Its vision of an integrated, prosperous, and peaceful Africa, driven by its own citizens and acting as a dynamic force globally, speaks directly to our current reality. Reclaiming this vision requires Africa to speak with one voice, strengthen its cohesion, and reinforce its continental and regional institutions. The African Continental Free Trade Area provides a concrete pathway in this regard. By strengthening intra-African trade, developing regional value chains, and supporting industrialisation, it can help transform Africa’s wealth into sustainable development and meaningful participation in global value-added production.

AFRICA AND THE NEW SCRAMBLE A Call for Urgent Continental Action

AFRICA AND THE NEW SCRAMBLE

A Call for Urgent Continental Action

Date | 16 February 2026

Abdul Mohammed, Senior Fellow at Amani Africa and Former Senior UN Official and Chief of Staff of AU High-level Panel on Sudan

We are living through a rupture in the global order.

This is not a passing crisis, a cyclical downturn, or a temporary disruption. It is a rupture—moral, political, institutional, and ideological. The assumptions that governed global life for decades are not merely eroding; they are being openly repudiated. Power is no longer cloaked in the language of universal values. It is asserted through identity, exclusion, hierarchy, and fear.

This rupture is not abstract. It is already reshaping how the world organizes power, mobility, security, and value. Within this context, Africa now confronts a new scramble—quieter than the colonial past, but no less consequential.

The United States’ 2025 National Security Strategy’ illustrates this shift. It reads less like a traditional security document and more like a civilizational manifesto. Its central anxiety is not war, climate collapse, or nuclear escalation—but migration. Immigration is framed not as a policy challenge, but as a civilizational threat. A racialized fear is projected outward onto the world.

Stopping migration has become doctrine—exported through alliances, embedded in diplomacy, and enforced far beyond American borders. This is not simply border control; it is population control by proxy. Collective security is mocked. International cooperation is belittled. Global public goods are treated as illusions. Multilateralism itself is recast as a shackle—an obstacle to the exercise of raw power.

From certain capitals, this may appear to be a return to classical geostrategy, in which the world is divided into spheres of influence. Across the global South, however, it evokes something more familiar. Colonialism was geo-kleptocracy.

Those who witnessed Apartheid and its ‘homelands‘—low-wage reservoirs designed for extraction—will recognize the pattern. Stealing countries was the ultimate form of global kleptocracy.

For Africa, this shift is existential.

A century and a half ago, the continent was carved up by imperial powers who treated sovereignty as a commodity to be sliced, ranked, and traded. Aborting the organic process of the forming of indigenous political entities, this process produced the most arbitrarily contrived fragments in the service of colonial powers. This bequeathed Africa administrative shells designed for extraction, not autonomy.

The leaders of independence believed they had won the political kingdom. Yet when they took control of their new capitals, they discovered that the structures they inherited were little more than fortified trading posts—designed to serve the interest of the metropole and for stifling strategic autonomy and self-determination.

Africa’s agency has therefore never rested in the nation-state alone. It has rested in collective action. In Pan-Africanism.

Thus viewed, Pan-Africanism is not nostalgia. It is political technology for survival in a hostile world system and for unshackling Africa from the chains that locked it into the global system.

As Africa sought and seeks an international system in which it gets its due, it does not consider multilateralism anchored on the UN to be optional. It is existential.

Multilateralism is existential particularly where historical, political, socio-economic and geo-strategic conditions get in the way of Pan-African collective action.

Africa has often been failed by multilateral institutions. History is equally clear: Africa (as shackled as it has been and let down by its leaders) without multilateralism is Africa without leverage.

This is why attempts to bypass African multilateral institutions—whether in peace processes, economic negotiations, or security arrangements—are not neutral acts. They replace collective leverage with bilateral dependency.

THE NEW SCRAMBLE

Today’s scramble does not arrive with gunboats. It arrives through contracts, currency, legal instruments, digital infrastructure agreements, and critical minerals partnerships. Sometimes there are spectacular displays of force meant to send a message. More often, the mechanisms are quiet.

The danger is not engagement. Africa must engage the world. The danger lies in how Africa is engaging—fragmented, reactive, and uncoordinated—precisely at the moment when external actors are acting strategically when they engage Africa.

Fragmentation has become Africa’s primary strategic vulnerability.

Here is the paradox of our time. Africa has never mattered more. By 2030, nearly 1.7 billion people will live on the continent, including 40 percent of the world’s youth. Africa holds minerals essential to the green and digital transitions. Its geography anchors vital maritime routes.

In objective terms, Africa has leverage.

But leverage unused is leverage lost. And the reason is simple: disunity.

Fifty-five states negotiating separately. Trade deals concluded country by country. Mineral agreements signed in isolation. Data governance frameworks outsourced without shared standards.

External actors arrive with scale and long-term strategy. Africa responds with improvisation and short-term calculation. Even when individual deals appear attractive, their cumulative effect is erosion.

Fragmentation enables powerful actors to play states against one another—to extract concessions incrementally and shape rules Africa did not help write.

The pattern is not new. When preferential trade regimes were replaced by reciprocal arrangements, African economies suffered deeply. Industries collapsed and jobs disappeared. Yet the response was not collective; it was bilateral petitioning.

The same pattern now appears in critical minerals. Some states restrict exports. Others prioritize rapid extraction. Others advocate local processing. Each approach is rational on its own. Together, they form no strategy.

Without shared principles on value addition and safeguards, Africa remains a price-taker in industries it should help shape.

This fragmentation extends beyond economics—to migration policy, energy transition, and digital sovereignty. Africa is not setting the agenda. It is reacting to agendas set elsewhere.

Once again, sovereignty risks becoming a commodity—sliced, ranked, and traded. Not only by traditional great powers, but by rising middle powers as well.

Africa’s future is debated in rooms where Africans are either absent—or present without influence.

The emergence of private or semi-private diplomatic mechanisms raises further questions about the future of collective security. If mediation becomes transactional—if peace becomes an investment opportunity—what becomes of the principles embedded in the charters of continental and global institutions?

Will African institutions defend their mandates? Or will they defer to ad hoc structures shaped by private interest driven external power?

This dilemma is particularly acute because Africa’s own peace and security architecture has weakened. Norms exist. Institutions exist. But political will, commitment to Pan-Africanism and the drive for engaging in the difficult task of crafting imaginative collective solutions have withered.

Institutional limitation cannot become an alibi for capitulation. Moments of global upheaval demand coordination, moral courage, political imagination and leadership.

Africa does not require uniformity. It requires agreed minimums—baseline negotiating principles, solidarity mechanisms to prevent isolation, and the discipline to refuse piecemeal bargaining.

Africa must no longer negotiate its future piece by piece.

LEADERSHIP, SILENCE, AND RESPONSIBILITY

The most dangerous element of this moment is not external pressure. It is Africa’s silence.

That silence reflects a deeper leadership deficit. Too many leaders are products of fragile systems—elevated through survival skills, external sponsorship, or transactional compromise rather than vision and legitimacy.

At a moment demanding courage, Africa is governed by managerial survivalism. Bureaucratic Pan-Africanism administers decline instead of confronting history.

This vacuum invites manipulation. It emboldens insult. It fragments Africa state by state.

Africa has known another tradition—leaders who understood Africa not as geography, but as a political project.

That caliber of leadership is rare today. Yet Africa’s promise remains intact.

Africans must not accept defensive politics. A renewed Pan-Africanism—rooted in dignity, justice, and agency—is not optional. It is necessary.

Africa must engage the world as it is—but never at the cost of dignity.

IN CLOSING

The question is no longer whether Africa matters. It does.

The question is whether Africa will matter on its own terms and for its own interest.

History does not reward potential. It rewards organization and resolve.

The emerging global order is visible. The rank being assigned to Africa is visible. If that rank is accepted today, it may define the continent’s position for generations.

This is not a call for confrontation. It is a call for coordination.

If Africa acts together, this rupture can mark the beginning of strategic autonomy. If it does not, the new scramble will end quietly—without conquest, but with consequences just as enduring and damaging.

The responsibility rests in thought, political and organizational leadership.

History is watching.

AFRICA AND THE NEW SCRAMBLE A Call for Urgent Continental Action

AFRICA AND THE NEW SCRAMBLE

A Call for Urgent Continental Action

Date | 16 February 2026

Abdul Mohammed, Senior Fellow at Amani Africa and Former Senior UN Official and Chief of Staff of AU High-level Panel on Sudan

We are living through a rupture in the global order.

This is not a passing crisis, a cyclical downturn, or a temporary disruption. It is a rupture—moral, political, institutional, and ideological. The assumptions that governed global life for decades are not merely eroding; they are being openly repudiated. Power is no longer cloaked in the language of universal values. It is asserted through identity, exclusion, hierarchy, and fear.

This rupture is not abstract. It is already reshaping how the world organizes power, mobility, security, and value. Within this context, Africa now confronts a new scramble—quieter than the colonial past, but no less consequential.

The United States’ 2025 National Security Strategy’ illustrates this shift. It reads less like a traditional security document and more like a civilizational manifesto. Its central anxiety is not war, climate collapse, or nuclear escalation—but migration. Immigration is framed not as a policy challenge, but as a civilizational threat. A racialized fear is projected outward onto the world.

Stopping migration has become doctrine—exported through alliances, embedded in diplomacy, and enforced far beyond American borders. This is not simply border control; it is population control by proxy. Collective security is mocked. International cooperation is belittled. Global public goods are treated as illusions. Multilateralism itself is recast as a shackle—an obstacle to the exercise of raw power.

From certain capitals, this may appear to be a return to classical geostrategy, in which the world is divided into spheres of influence. Across the global South, however, it evokes something more familiar. Colonialism was geo-kleptocracy.

Those who witnessed Apartheid and its ‘homelands‘—low-wage reservoirs designed for extraction—will recognize the pattern. Stealing countries was the ultimate form of global kleptocracy.

For Africa, this shift is existential.

A century and a half ago, the continent was carved up by imperial powers who treated sovereignty as a commodity to be sliced, ranked, and traded. Aborting the organic process of the forming of indigenous political entities, this process produced the most arbitrarily contrived fragments in the service of colonial powers. This bequeathed Africa administrative shells designed for extraction, not autonomy.

The leaders of independence believed they had won the political kingdom. Yet when they took control of their new capitals, they discovered that the structures they inherited were little more than fortified trading posts—designed to serve the interest of the metropole and for stifling strategic autonomy and self-determination.

Africa’s agency has therefore never rested in the nation-state alone. It has rested in collective action. In Pan-Africanism.

Thus viewed, Pan-Africanism is not nostalgia. It is political technology for survival in a hostile world system and for unshackling Africa from the chains that locked it into the global system.

As Africa sought and seeks an international system in which it gets its due, it does not consider multilateralism anchored on the UN to be optional. It is existential.

Multilateralism is existential particularly where historical, political, socio-economic and geo-strategic conditions get in the way of Pan-African collective action.

Africa has often been failed by multilateral institutions. History is equally clear: Africa (as shackled as it has been and let down by its leaders) without multilateralism is Africa without leverage.

This is why attempts to bypass African multilateral institutions—whether in peace processes, economic negotiations, or security arrangements—are not neutral acts. They replace collective leverage with bilateral dependency.

THE NEW SCRAMBLE

Today’s scramble does not arrive with gunboats. It arrives through contracts, currency, legal instruments, digital infrastructure agreements, and critical minerals partnerships. Sometimes there are spectacular displays of force meant to send a message. More often, the mechanisms are quiet.

The danger is not engagement. Africa must engage the world. The danger lies in how Africa is engaging—fragmented, reactive, and uncoordinated—precisely at the moment when external actors are acting strategically when they engage Africa.

Fragmentation has become Africa’s primary strategic vulnerability.

Here is the paradox of our time. Africa has never mattered more. By 2030, nearly 1.7 billion people will live on the continent, including 40 percent of the world’s youth. Africa holds minerals essential to the green and digital transitions. Its geography anchors vital maritime routes.

In objective terms, Africa has leverage.

But leverage unused is leverage lost. And the reason is simple: disunity.

Fifty-five states negotiating separately. Trade deals concluded country by country. Mineral agreements signed in isolation. Data governance frameworks outsourced without shared standards.

External actors arrive with scale and long-term strategy. Africa responds with improvisation and short-term calculation. Even when individual deals appear attractive, their cumulative effect is erosion.

Fragmentation enables powerful actors to play states against one another—to extract concessions incrementally and shape rules Africa did not help write.

The pattern is not new. When preferential trade regimes were replaced by reciprocal arrangements, African economies suffered deeply. Industries collapsed and jobs disappeared. Yet the response was not collective; it was bilateral petitioning.

The same pattern now appears in critical minerals. Some states restrict exports. Others prioritize rapid extraction. Others advocate local processing. Each approach is rational on its own. Together, they form no strategy.

Without shared principles on value addition and safeguards, Africa remains a price-taker in industries it should help shape.

This fragmentation extends beyond economics—to migration policy, energy transition, and digital sovereignty. Africa is not setting the agenda. It is reacting to agendas set elsewhere.

Once again, sovereignty risks becoming a commodity—sliced, ranked, and traded. Not only by traditional great powers, but by rising middle powers as well.

Africa’s future is debated in rooms where Africans are either absent—or present without influence.

The emergence of private or semi-private diplomatic mechanisms raises further questions about the future of collective security. If mediation becomes transactional—if peace becomes an investment opportunity—what becomes of the principles embedded in the charters of continental and global institutions?

Will African institutions defend their mandates? Or will they defer to ad hoc structures shaped by private interest driven external power?

This dilemma is particularly acute because Africa’s own peace and security architecture has weakened. Norms exist. Institutions exist. But political will, commitment to Pan-Africanism and the drive for engaging in the difficult task of crafting imaginative collective solutions have withered.

Institutional limitation cannot become an alibi for capitulation. Moments of global upheaval demand coordination, moral courage, political imagination and leadership.

Africa does not require uniformity. It requires agreed minimums—baseline negotiating principles, solidarity mechanisms to prevent isolation, and the discipline to refuse piecemeal bargaining.

Africa must no longer negotiate its future piece by piece.

LEADERSHIP, SILENCE, AND RESPONSIBILITY

The most dangerous element of this moment is not external pressure. It is Africa’s silence.

That silence reflects a deeper leadership deficit. Too many leaders are products of fragile systems—elevated through survival skills, external sponsorship, or transactional compromise rather than vision and legitimacy.

At a moment demanding courage, Africa is governed by managerial survivalism. Bureaucratic Pan-Africanism administers decline instead of confronting history.

This vacuum invites manipulation. It emboldens insult. It fragments Africa state by state.

Africa has known another tradition—leaders who understood Africa not as geography, but as a political project.

That caliber of leadership is rare today. Yet Africa’s promise remains intact.

Africans must not accept defensive politics. A renewed Pan-Africanism—rooted in dignity, justice, and agency—is not optional. It is necessary.

Africa must engage the world as it is—but never at the cost of dignity.

IN CLOSING

The question is no longer whether Africa matters. It does.

The question is whether Africa will matter on its own terms and for its own interest.

History does not reward potential. It rewards organization and resolve.

The emerging global order is visible. The rank being assigned to Africa is visible. If that rank is accepted today, it may define the continent’s position for generations.

This is not a call for confrontation. It is a call for coordination.

If Africa acts together, this rupture can mark the beginning of strategic autonomy. If it does not, the new scramble will end quietly—without conquest, but with consequences just as enduring and damaging.

The responsibility rests in thought, political and organizational leadership.

History is watching.

Kenya's President Ruto proposes an African foreign policy for repositioning Africa at the 39th AU Assembly

Kenya's President Ruto proposes an African foreign policy for repositioning Africa at the 39th AU Assembly

Date | 14 February 2026

Solomon Ayele Dersso, PhD, Founding Director, Amani Africa

In a report he presented to the 39th Ordinary Session of the AU Assembly on 14 February 2026 underway at the AU Headquarters in his capacity as the African Union (AU) Champion for the Institutional Reform of the AU, President Ruto proposed the development of ‘African foreign policy’ by five ‘foreign policy experts’ for submission and adoption by the AU Assembly during its 40th ordinary session.

This is one of many proposals put forward by the Champion in the quest to overhaul the AU institutions and make the AU fit for the challenges and changes taking place in the world. As the report pointed out, ‘[i]n an era shifting global power dynamics, Africa must reposition itself as a coherent and influential actor in shaping international norms, security and governance.’

There are at least two factors that make such repositioning imperative for Africa and the AU. The first relate to the expanding profile of the AU in global governance and the increasing demand and need for Africa to adopt position on matters of global governance. These expectations arise, among others, in the context of AU’s membership in the G20 and the role of the African three plus (A3) members of the UN Security Council. The second factor is the emergence of what Abdul Mohamed called ‘assertive external actors pursuing bilateral advantage at the expense of collective order.’

As the report that Amani Africa released on the eve of the AU Assembly observed, ‘[d]espite growing demand for the continent’s resources, diplomatic support, and political alignment, Africa continues to approach international partnerships largely through fragmented bilateral channels.’ This continues to cost Africa enormously as it limits collective leverage and reinforces asymmetrical relationships.

As natural resources, particularly critical minerals, increasingly become sites of geopolitical contestation, in a time when multilateral frameworks are unravelling and transactional and extractivist approaches take primacy, African states are exposed to another scramble for Africa, with major and middle powers targeting them individually & hence at their weakest. As Amani Africa’s report pointed out, Africa risks remaining exposed to competitive external pressures and transactional and extractive arrangements that avail Africa, and prioritise fleeting benefits that are no more than crumbs over substantive and strategic immediate and long-term interests.’

It would indeed be irresponsible for Africa to continue in a business-as-usual manner as far as international relations are concerned in the face of the unravelling of the multilateral system. Doing so would be condemning Africa to the vagaries of global disorder. It is against this background that Amani Africa’s report situated the development of common African foreign policy both as strategic imperative and a timely act. It thus held, Institutionalising a common pan-African foreign policy would provide the political and strategic framework on how Africa can advance its collective interests and project its voice effectively. Apart from serving as a necessary tool for shielding African states from the predatory tendencies of a time in which ‘anarchy is loosed upon the world’, such a common pan-African foreign policy would provide the framework for more effectively negotiating and coordinating common positions.’

The Champion’s proposal for African Common Foreign Policy avails Africa additional advantages. Such a common foreign policy also becomes ‘the basis for undertaking periodic continental strategic assessment that could avail unified analysis of global trends, external actors’ strategies, and emerging risks, thereby enabling Africa to plan and engage proactively rather than reactively.

For the AU as well, such a common African foreign policy would also provide the much-needed point of reference for reorganising and reimagining the role of the AU’s representational offices.’

Surely, adopting such a common foreign policy is necessary but not sufficient. Without commitment to such a policy and willingness to act collectively, Africa is unlikely to harness the opportunities such a foreign policy avails. It thus needs to be backed by an institutional framework that catalyses political will and commitment for the implementation of the policy.