The Pan-Africanist Podcast - Episode 6

Exclusive interview: H.E. Mahamoud Youssouf, candidate for AU Commission Chairperson election

Dec 6, 2024

Provisional Programme of Work of the Peace and Security Council for December 2024

Provisional Programme of Work of the Peace and Security Council for December 2024

Date | December 2024

In December, the Republic of Djibouti will assume the role of chairing the African Union (AU) Peace and Security Council (PSC) under the leadership of H.E. Ambassador Abdi Mahmoud Eybe, Permanent Representative of Djibouti to the AU.

The Provisional Programme of Work (PPoW) for the month envisages four substantive sessions covering six agenda items. Except for one session envisaged to take place at the ministerial level, all the sessions are scheduled to take place at the ambassadorial level. Five of the six agenda items are on thematic issues. The remaining one agenda is dedicated to a country situation. No open session is stipulated in the PPoW. All sessions are scheduled to be held virtually.

In addition to the sessions, the PSC will also hold the annual High-Level Seminar on Peace and Security in Africa and its retreat with the African Peer Review Mechanism in Johannesburg. Additionally, the PSC is expected to hold informal consultation with countries suspended from the AU on the transition processes and the peace and security issues affecting them.

On 1 December, the month will kick off with the ‘11th Annual High-Level Seminar on Peace and Security in enhancing cooperation between the AU PSC and the African Members of the UN Security Council in Addressing Peace and Security issues on the Continent’. This is held in accordance with Article 17(3) of the PSC Protocol which stipulates close working relationship between the PSC and the African members of the United Nations Security Council (UNSC).

As outlined in the information note, this year’s edition of the High-Level Seminar is envisaged to focus particularly ‘on: a) Building Integrated Capacities for effectively combating terrorism and violent extremism; b) Implementation of the Pact of the Future focusing on UN Security Council Reform and Implementation of the UN Security Council Resolution 2719 (2023); and c) Coordination between the PSC and the A3 Plus. The Seminar will also receive a Briefing on the Conclusions of the Ministerial Meeting of the A3 Plus, and last but not least, it will consider the status of implementation of the Conclusions of the 10th Annual High-Level Seminar held in December 2023 and also adopt the Manual on the Modalities of Engagements between the PSC and the A3 Plus (Oran Process).’ It is to be recalled that the adoption of the Manual was postponed from last year in order to allow further inputs from member states. It remains to be seen whether the adoption of the Manual will actually take place as planned. In addition to members of the PSC, the seminar is expected to feature, as per the established practice, the current A3 members Plus One, incoming members of the A3 and Friends of the High-Level Seminar.

After Oran, on 5 December, the PSC will convene a session to review the implementation of PSC Decisions. This session, indicated in the Annual Programme of Work to take place twice a year, aims to review the state of the implementation of the decisions of the Council. As with the decisions of the AU, including that of the Assembly, non-implementation is a major challenge facing the decisions of the PSC. In 2017, the PSC took a decision following its retreat on its working methods that ‘the Committee of Experts shall, every six months, before the Ordinary Session of the Assembly, submit a matrix of implementation of all PSC decisions for consideration by the PSC.’ Since 2022, the PSC Secretariat took responsibility and developed the matrix for the implementation of PSC decisions as an instrument for monitoring follow-up. It is within this framework that the PSC will convene this proposed session.

On 10 December, the PSC will hold a session with two related agenda items. The first is on Consideration of the AU/UN Policy Paper on Enhancing AU Continental Early Warning System (CEWS) and Early Action. This is a paper prepared, under the guidance of the Commissioner for Political Affairs, Peace and Security (CPAPS), through technical input from the UN, which provides an assessment of the institutional and operational issues affecting the CEWS and AU’s conflict prevention work. It is anticipated that the CPAPS will share with PSC members the contents of the paper. The second agenda item concerns the review of the Country Structural Vulnerability and Resilience Assessment (CSVRA) and Country Structural Vulnerability Mitigation Strategies (CSVMS). The CSVRA and CSVMS are developed following the request of the PSC in its 463rd session for the development of a structural vulnerability assessment. Subsequently and following the completion, the PSC at its 901st meeting, the PSC encouraged ‘Member States to make full use of the tools available at the Commission for structural conflict prevention, including the Country Structural Vulnerability and Resilience Assessment (CSVRA) and Country Structural Vulnerability Mitigation Strategies (CSVMS).’ As voluntary instruments developed to help member states in assessing their vulnerability and resilience, these instruments did not attract a large number of subscribers. Thus far, only Cotd’Ivoire, Ghana, and Zambia have volunteered to undertake the assessment. While Ghana completed the assessment, Zambia went through the assessment in 2021, and Cotd’Ivoire’s is still pending.

The following session is scheduled for 12 December, focusing on two agenda items. The first is an update on the progress made towards silencing the guns. This is being convened within the framework of the decision of the AU to review the implementation of the flagship project every two years. The 14 Extraordinary Summit of the AU decided to extend Silencing the Guns for a period of ten (10) years (2021-2030), with periodic reviews every two (2) years.’ This session is thus expected to present the PSC with the opportunity to review the state of peace and security on the continent and the gap between the ambition of the STG flagship project and the realities on the ground. As a review session, it is expected that it would put a spotlight on the setbacks being faced in the journey to achieve this noble objective and how and what kind of adjustments can be made to stem the tide of the increase in the number and geographic spread of conflicts. The second agenda focuses on the consideration and adoption of the draft program of work for the month of January 2025.

The following week, the PSC will travel to Johannesburg, South Africa, for the 4th Annual Joint Retreat between the PSC and African Peer Review Mechanism (APRM), which will be held on 16 and 17 December.

The same week, on 19 December, the PSC will convene its first and only country-specific ministerial-level session for the month on ‘Consideration of the situation in Somalia and Post-ATMIS security Arrangements.’ This session is initiated in a context in which the end of ATMIS is envisaged to be 31 December 2024 while progress in finalising the preparations for and the design of the successor mission, the AU Stabilization and Support Mission to Somalia (AUSSOM), has stalled (See the 27 October 2024 edition of Insights on the PSC). On the one hand, this ministerial session has to provide guidance on how to manage the possibility of AUSSOM not becoming operational by 1 January 2025. On the other hand, it also needs to find a way out of the dispute over the participation of Ethiopia in AUSSOM as a troop contributing country. While Ethiopia as troop contributing country of ATMIS expects to continue to be part of AUSSOM, Somalia expressed its opposition to participation of Ethiopian troops unless Ethiopia retracts the memorandum of understanding it signed with Somaliland on access to the sea and the establishment of a naval base.

The final substantive activity of the PSC for the month concerns informal consultation on countries in political transition. Since April 2023, the PSC adopted the format of informal consultation as a way of overcoming the limitations that comes with suspension of AU member states from the AU and facilitating direct engagement with representatives of affected countries. It takes place in a venue different from the chambers of the PSC. No formal outcome is anticipated.

In addition to the foregoing, the PPoW encompasses a meeting of the Committee of Experts (CoE) on 9 December in preparation for the ministerial meeting on Somalia and Post-ATMIS security Arrangements. They are also scheduled to consider the annual indicative program of work for 2025. The CoE will also have a meeting to consider the Draft Report of the PSC on its activities and the State of Peace and Security in Africa.

Monthly Digest on The African Union Peace And Security Council - October 2024

Monthly Digest on The African Union Peace And Security Council - October 2024

Date | October 2024

In October 2024, the African Union (AU) Peace and Security Council (PSC) undertook its activities under the chairship of the Arab Republic of Egypt. The PSC’s initial Provisional Programme of Work (PPoW) envisaged eight substantive sessions with nine agenda items to be covered for the month. While the PPoW underwent two revisions, this mainly led to shifts in planned sessions and activity dates.

Can a unified leadership of the A3+ help in navigating the geopolitical gridlock in the UN Security Council in relation to African files?

Can a unified leadership of the A3+ help in navigating the geopolitical gridlock in the UN Security Council in relation to African files?

Date | 28 November 2024

Solomon Ayele Dersso, PhD

Founding Director, Amani Africa

Kaleab Tadesse Sigatu

Associate Researcher, Amani Africa

The 18 November 2024 Russian veto against the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) resolution on Sudan triggered understandable consternation. This development raises a major policy issue for the African Union (AU) and the three African members of the UNSC plus (A3 plus – currently made up of Algeria, Mozambique, Sierra Leone plus Guyana). This issue principally concerns how the A3 plus can facilitate consensus in the UNSC on African files and thereby help overcome the impact of the hardening rift in the Permanent five members of the UNSC (P5) and the rising resort to the use of veto even in relation to African files as highlighted by the recent voting in the UNSC on a resolution on Sudan.

In recent years, the space for effective collective action in the UNSC has enormously dwindled. This in the main is owing to the rising geopolitical contestation on the part of the P5. One of the indices of this is the increasing use of the veto by the permanent five members of the UNSC. In 2024, a total of 7 vetoes were cast, making it the highest number of vetoes in a single calendar year since 1989.

While the deadlock in the P5 has until recently had limited impact on African files, this is no longer the case. As a result, the deepening geopolitical division in the P5 is also affecting African files on which the P5 have generally managed to achieve consensus in previous years. Such is particularly the case in instances in which the A3 are unable to take a unified position and robust African Union (AU) Peace and Security Council (PSC) backing is lacking.

On 18 November 2024, the UNSC failed, on account of a veto by Russia, to adopt a Resolution aimed at advancing measures to protect civilians in Sudan, as the war grinds on, killing tens of thousands of Sudanese and causing the largest displacement crisis in the world, with over 13 million people displaced. The draft resolution demanded the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) honour and fully implement their commitments in the ‘Declaration of Commitment to Protect the Civilians of Sudan’, which was signed by both sides in Jeddah on 11 May 2023.

The draft text was co-authored by the UK (the penholder on the Sudan file) and Sierra Leone. The UK apparently invited the A3 plus members (Algeria, Mozambique, Sierra Leone, and Guyana) to be co-authors on the draft resolution. However, the A3 plus members were unable to reach a unified position on taking this as a group. This led to Sierra Leone serving as the only co-penholder of the resolution. Sudan’s representative was invited to participate in the meeting.

Russia’s veto has the appearance of being a result of its increasing shift towards the Transitional Sovereign Council and the exchanges during the voting also suggest it is also a manifestation of the divide in the P5 reflecting the tension between Russia and the UK, which is the pen holder on Sudan. Yet, the fact that the A3 plus, despite voting in favour of the resolution on 18 November, were neither fully united nor took the lead on the file might have also played a role. Apart from the inability of the A3 plus to join in co-pen holding for drafting the particular resolution, the A3 plus did not take the same position on various aspects of the resolution during negotiation on the draft, as documented in SCR analysis.

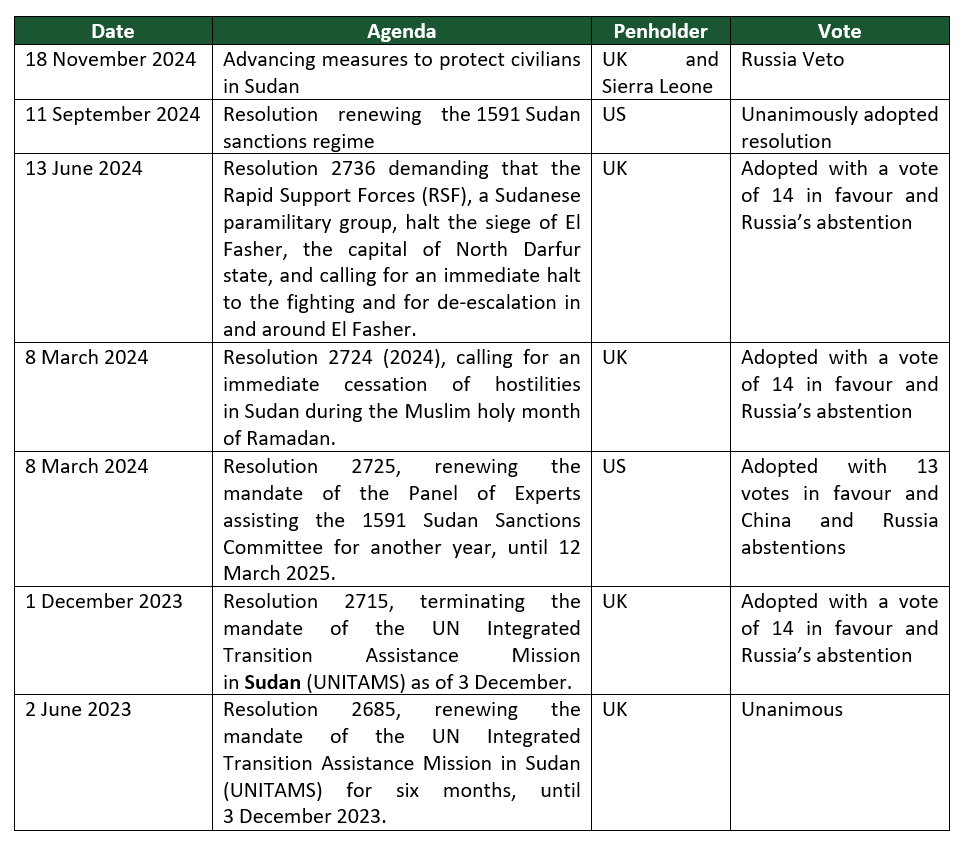

As shown in the table below, there have at least been seven instances in which the UNSC considered products on the situation in Sudan since the outbreak of the current war in April 2023. While Russia abstained from many of them, the UNSC managed to adopt all of them until the latest resolution was vetoed by Russia.

UN Security Council Resolutions on Sudan

Source: Compilation by author based on materials from the Security Council Report

The latest voting on Sudan is clearly a warning sign, if not a turning point, that UNSC products on African files are no longer immune from being vetoed. This is particularly true in cases where the A3 plus are not fully united and not on the lead on a file. The upshot of this is that there is room for the A3 plus and the AU, particularly through the PSC, to help shield African files from the most severe manifestation of the tension in the P5. For this, all that is needed is to build on and expand the existing working arrangement that facilitates A3 plus collective stand.

It is worth noting that in order to mitigate the fact that Africa has no permanent representation in the UNSC with full prerogatives accorded to the P5, a major avenue the AU instituted the constitution of the A3 into a unified block. This has increasingly enabled the A3 plus and the AU to exercise rising influence in the UNSC as documented here and here, despite the fact that it may at times have the effect of limiting the UNSC’s engagement. It is anticipated that the influence of the A3 plus will further increase in the context of the deepening rift in the P5.

In view of the latest failure of the UNSC to adopt the resolution on Sudan, one potential area for such growth in the influence of the A3 plus is how the A3 plus both achieve unity and takes lead in drafting of UNSC products on African files. If such a way of organising is used for enhancing effective engagement of the UNSC rather than preventing its role, it has the potential for facilitating consensus and overcoming the gridlock in the P5 and avoiding veto.

This however requires addressing at least two challenges in how the role of the A3 is organised. The first of these, which is advanced by the AU policy organs and the A3 themselves, is the assumption of the role of pen-holding by the A3 plus particularly on African files. While there has been progress in this respect in recent years, the A3 plus have as yet to effectively assume this critical, if challenging, role. The second area is the crafting of unified position by the A3plus to speak with one voice and negotiate as a block, something on which the A3 plus has achieved substantial progress.

Furthermore, if the AU PSC institutes a practice of providing clear guidance on African files under consideration in the UNSC, thereby throwing its full weight behind the lead of the A3, it could enhance the legitimacy and support for A3 plus initiated resolution. Such strong engagement and backing of the PSC facilitates the conditions for achieving consensus in the UNSC and making vetoing, very difficult, although not necessarily impossible.

As the PSC convenes the 11 annual high-level seminar of Oran on peace and security focusing on the role of the A3 plus on 1-2 December 2024 in Oran, Algeria, one of the issues worth reflecting on is how to advance effective international action by the UNSC by limiting the deleterious impacts of the deepening contestation in the P5 on African files. As discussed above, the case of the vetoed UNSC resolution on Sudan offers a useful basis for informing the elaboration of such policy approach.

The content of this article does not represent the views of Amani Africa and reflect only the personal views of the authors who contribute to ‘Ideas Indaba’