LE SOUDAN: UNE TRAGÉDIE AFRICAINE QUI EXIGE UN SURSAUT COLLECTIF

LE SOUDAN: UNE TRAGÉDIE AFRICAINE QUI EXIGE UN SURSAUT COLLECTIF

Date | 10 février 2026

INTRODUCTION

Le Soudan est aujourd’hui l’épicentre de l’un des conflits les plus meurtriers au monde et de l’une de ses pires crises humanitaires. Les chiffres parlent d’eux-mêmes : depuis 2023, plus de 150 000 personnes ont perdu la vie du fait des violences perpétrées par les belligérants et d’autres causes connexes ; environ 7,3 millions ont été nouvellement déplacées à l’intérieur du pays – s’ajoutant aux 2,3 qui l’avaient déjà été avant le déclenchement du conflit actuel, ce qui porte le chiffre total des déplacées à 9,6 millions ; 4,3 millions ont trouvé refuge dans les États voisins; et plus de 30 millions de personnes –soit les deux tiers de la population – dépendent désormais de l’aide humanitaire. Les atrocités commises dépassent l’entendement. La bataille pour le contrôle d’El-Fasher – sa chute aux mains des Forces de soutien rapide (FSR) et les récits insoutenables qui ont suivi – a ravivé les échos les plus sombres d’une tragédie antérieure : la politique de la terre brûlée pratiquée au Darfour en réaction à la rébellion armée qui y éclata en 2003. La crainte est aujourd’hui vive de voir ce qui s’est déroulé dans cette localité se reproduire ailleurs.

The 2026 Elections of the Ten Members of the Peace and Security Council: The Dynamics, Process and Candidates

The 2026 Elections of the Ten Members of the Peace and Security Council: The Dynamics, Process and Candidates

Date | 5 February 2026

INTRODUCTION

30 March 2026 will mark the end of the mandate of 10 members of the African Union (AU) Peace and Security Council (PSC) who were elected for a two-year term in February 2024 during the 37th ordinary session of the AU Assembly. Since the election for the three-year term was held during the 38th AU Assembly in February 2025, the 2026 election of the PSC will be limited to these ten two-year term seats in the Council. Unlike the three-year term seats, which are allocated equally to the five regions of the AU, the regional allocation of the ten two-year term seats is based on the number of states in the different regions at the time of the adoption of the PSC Protocol. Thus, pursuant to the Protocol Establishing the PSC and the Modalities on the Elections of the PSC, the two-year term membership of the PSC is allocated for the five regions as follows: three seats for West Africa, two seats for Central, East and Southern Africa regions, and one seat for North Africa.

Provisional Programme of Work of the Peace and Security Council for February 2026

Provisional Programme of Work of the Peace and Security Council for February 2026

Date | February 2026

The Arab Republic of Egypt will assume the chairship of the African Union (AU) Peace and Security Council (PSC) for the month of February. The Provisional Programme of Work (PPoW) for the month includes four substantive sessions covering five agenda items. Among the five agenda items, two will cover country-specific situations, two will cover thematic issues, and another session will consider and adopt the ‘Report of the Activities of the PSC and the State of Peace and Security in Africa.’ The country-specific sessions will be convened at the ministerial level, while the thematic sessions will be held at the ambassadorial level. In addition, the PPoW includes two informal consultations – one with Sudan and another with Member States in Political Transition. The 48th Ordinary Session of the AU Executive Council and the 39th Ordinary Session of the Assembly will also be held during this month. A field visit is also planned for the last week of the month. Two meetings will be conducted physically, while two others will take place virtually, with virtual meetings having become part of the norm through practice.

On 3 February, the PSC will convene its first substantive session of the month to consider and adopt the ‘Report on the Activities of the Peace and Security Council and the State of Peace and Security in Africa.’ The session was initially scheduled for January 2026 but was subsequently postponed. Pursuant to Article 7 (q) of the PSC Protocol and in keeping with established institutional practice, the Council will, following its deliberations, transmit the report to the 39th Ordinary Session of the AU Assembly, which is scheduled for 14 to 15 February 2026. The report is anticipated to present a consolidated account of the PSC’s undertakings during the reporting period, alongside an analytical appraisal of prevailing trends and developments shaping the continent’s peace and security environment.

On 10 February, the PSC will receive two briefings on the situations in Sudan and Somalia at the ministerial level. The session will begin with a briefing on Sudan, preceded by an informal consultation at the ministerial level, which is expected to feature Sudan’s minister. The briefing follows the PSC’s 1319th session held in December 2025, during which the Council agreed to convene a Ministerial meeting on Sudan on the margins of the 39th Ordinary Session of the AU Assembly. During that session, the Council welcomed the establishment of the Quintet—the latest configuration in Sudan’s peace efforts—bringing together five multilateral organisations (the AU, IGAD, the UN, the Arab League, and the EU) with the aim of anchoring the political and civilian peace process under AU leadership. Cognisant of the emergence of a de facto two-pronged peacemaking architecture for Sudan (one focusing on ceasefire or humanitarian truce and the other involving the political/civilian track), the Council also called on members of the Quintet and the Quad to work closely together to ensure greater synergy in mediation efforts. In this context, one of the updates expected in the upcoming briefing concerns the consultative meeting of the Quintet held in Egypt in mid-January and the outcomes of that engagement. The briefing is also expected to provide a platform for the PSC to follow up on its previous decisions, including the establishment of an Inter-Departmental Task Force to coordinate humanitarian efforts, receive the latest updates on the security situation since the December meeting, explore ways to enhance coordination among the various mediation initiatives, and recalibrate the AU’s engagement in support of an inclusive, Sudanese-led political dialogue. It would not also be surprising if the issue of the lifting of Sudan’s suspension would arise, more so on account of the fact that it would be one of the issues that the representative of Sudan may likely raise during the informal consultation.

On the same date, the PSC will also receive a briefing on the situation in Somalia, expectedly with a particular focus on the operation and financing of the African Union Support and Stabilisation Mission in Somalia (AUSSOM). At its last meeting, held on 15 December 2025, the PSC considered the report of the Chairperson of the AU Commission, which highlighted key developments in Somalia and progress in the implementation of AUSSOM’s mandate during the period from July to December 2025. The report covered, inter alia, progress towards the operationalisation of the mission, as well as the financial and logistical challenges it continues to face. Against the backdrop of the financial, logistical, operational, and political constraints affecting the mission, the Chairperson of the Commission outlined three options for the PSC’s strategic guidance on the future of AUSSOM. During that session, the Council, instead of pronouncing itself on the proposed options, requested the AU Commission to submit a detailed report elaborating on each option, including their implications for the sustainability of AUSSOM and its operations. The Council further requested the Commission to urgently convene a meeting of AUSSOM TCCs/PCCs at the level of Chiefs of Defence Forces to deliberate on the three options and submit their recommendations for the Council’s consideration. Of immediate interest for the upcoming ministerial session will be to hear from the AU Commission on the PSC’s request for the Commission to fast-track the immediate release of the allocated funds to AUSSOM and to report on its implementation to the next meeting of the Council.’

After the 39th AU Summit, on 19 February, the PSC will hold an open session on Climate, Peace and Security. The last time the PSC held a session on this subject was at its 1301st session of September 2025, which situated the climate-security engagement firmly within the wider climate change policy framework, thereby eschewing the risk of bifurcation between the climate change policy process and the climate, peace and security policy making. Apart from the impact of climate change induced depletion of scarce natural resources on which people depend for their livelihoods including water and pasture on conflicts in the Sahel and Lake Chad Basin, discussions are likely to focus on strengthening evidence-based and conflict-sensitive approaches, mobilising adequate and predictable climate finance for adaptation, loss and damage and a just transition, and advancing the integration of climate indicators into early warning and peace and security mechanisms. The session may also provide an update on progress toward the Common African Position (CAP) on Climate, Peace and Security, including ongoing consultations with AU Member States, the African Group of Negotiators and RECs/RMs, as well as its expected alignment with AU climate frameworks and the Paris Agreement – with finalisation now anticipated ahead of COP31.

On 24 February, the PSC will hold a consultation with the Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO), the World Food Programme (WFP), and the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD) on the nexus between food, peace and security. The session aims to deepen the Council’s understanding of how conflict, climate shocks and food insecurity reinforce one another across the continent. While the PSC has previously addressed food insecurity within its humanitarian agenda, it was at its 1083rd session of 9 May 2022 that the Council explicitly dedicated attention to the link between food security and conflict and requested regular briefings by the AU Commission in collaboration with relevant regional institutions. The discussion is additionally expected to build on issues observed in various conflict settings, including the impact of armed conflict on agricultural production, food systems, displacement and market access, as well as on how food assistance, rural development and resilience-building interventions can contribute to conflict prevention and peacebuilding. FAO is expected to provide technical analysis on food security trends and agricultural systems, WFP will draw on operational data from conflict-affected settings where millions depend on emergency food assistance, and IFAD is expected to highlight long-term investments in smallholder livelihoods and rural resilience in fragile contexts. The urgency of this consultation is underscored by ongoing conflicts such as in Sudan, where violence has driven famine in parts of the country, and in the eastern Democratic Republic of Congo, where sustained insecurity has disrupted farming and supply chains, contributing to acute food insecurity affecting tens of millions.

On 25 February, the PSC is expected to have a field visit. However, not much detail is provided at the time of finalising this edition of Insights on the PSC and going to print.

The month will conclude on 27 February with an informal consultation between the Council and Member States currently in political transition, namely Burkina Faso, Guinea-Bissau, Madagascar, Mali, Niger and Sudan. This will be the fifth such consultation since the PSC institutionalised this format within its working methods following its 14th Retreat on Working Methods in November 2022. Held in accordance with Article 8(11) of the PSC Protocol, the consultations are held to enable direct engagement with representatives of Member States suspended from AU activities due to unconstitutional changes of government. The session will assess progress made and challenges encountered in ongoing transition processes and consider how the PSC can further strengthen its support for the political normalisation of the affected Member States, building on discussions held during the December 2025 session. No formal outcome document is expected.

The PPoW in footnotes also includes the presentation of the Report on the Activities of the PSC for 2025 and the State of Peace and Security in Africa to the AU Assembly. This is expected to happen on 14-15 February during the 39th AU Summit of the Assembly. As per the current practice, Egypt, as Chairperson of the PSSC, will introduce and present a summary followed by a full presentation of the report by the Commissioner for Political Affairs, Peace and Security (PAPS). However and in a commendable working methods improvement, for the first time, the proposed draft agenda of the AU Assembly introduces a different approach that singles out the major conflict situations for a dedicated and focused discussion. These are: a) progress report on the AU mediation in Eastern DRC, b) Situation in Sudan and South Sudan, and c) Situation in the Sahel.

In addition to the foregoing, the PSC’s Committee of Experts (CoE) is scheduled to convene two virtual meetings and one physical meeting during the month. The first virtual meeting, to be held on 5 February, will focus on preparations for the ministerial-level sessions on Sudan and Somalia scheduled for 10 February. The other will be a physical meeting on 20 February to convene the inaugural meeting of the PSC Subcommittee on Post-Conflict Reconstruction and Development (PCRD). The final CoE meeting of the month will be held virtually on 23 February and will feature a briefing by the AU Artificial Intelligence Advisory Group on Governance, Peace and Security.

Provisional Programme of Work of the Peace and Security Council for February 2026

Provisional Programme of Work of the Peace and Security Council for February 2026

Date | February 2026

The Arab Republic of Egypt will assume the chairship of the African Union (AU) Peace and Security Council (PSC) for the month of February. The Provisional Programme of Work (PPoW) for the month includes four substantive sessions covering five agenda items. Among the five agenda items, two will cover country-specific situations, two will cover thematic issues, and another session will consider and adopt the ‘Report of the Activities of the PSC and the State of Peace and Security in Africa.’ The country-specific sessions will be convened at the ministerial level, while the thematic sessions will be held at the ambassadorial level. In addition, the PPoW includes two informal consultations – one with Sudan and another with Member States in Political Transition. The 48th Ordinary Session of the AU Executive Council and the 39th Ordinary Session of the Assembly will also be held during this month. A field visit is also planned for the last week of the month. Two meetings will be conducted physically, while two others will take place virtually, with virtual meetings having become part of the norm through practice.

On 3 February, the PSC will convene its first substantive session of the month to consider and adopt the ‘Report on the Activities of the Peace and Security Council and the State of Peace and Security in Africa.’ The session was initially scheduled for January 2026 but was subsequently postponed. Pursuant to Article 7 (q) of the PSC Protocol and in keeping with established institutional practice, the Council will, following its deliberations, transmit the report to the 39th Ordinary Session of the AU Assembly, which is scheduled for 14 to 15 February 2026. The report is anticipated to present a consolidated account of the PSC’s undertakings during the reporting period, alongside an analytical appraisal of prevailing trends and developments shaping the continent’s peace and security environment.

On 10 February, the PSC will receive two briefings on the situations in Sudan and Somalia at the ministerial level. The session will begin with a briefing on Sudan, preceded by an informal consultation at the ministerial level, which is expected to feature Sudan’s minister. The briefing follows the PSC’s 1319th session held in December 2025, during which the Council agreed to convene a Ministerial meeting on Sudan on the margins of the 39th Ordinary Session of the AU Assembly. During that session, the Council welcomed the establishment of the Quintet—the latest configuration in Sudan’s peace efforts—bringing together five multilateral organisations (the AU, IGAD, the UN, the Arab League, and the EU) with the aim of anchoring the political and civilian peace process under AU leadership. Cognisant of the emergence of a de facto two-pronged peacemaking architecture for Sudan (one focusing on ceasefire or humanitarian truce and the other involving the political/civilian track), the Council also called on members of the Quintet and the Quad to work closely together to ensure greater synergy in mediation efforts. In this context, one of the updates expected in the upcoming briefing concerns the consultative meeting of the Quintet held in Egypt in mid-January and the outcomes of that engagement. The briefing is also expected to provide a platform for the PSC to follow up on its previous decisions, including the establishment of an Inter-Departmental Task Force to coordinate humanitarian efforts, receive the latest updates on the security situation since the December meeting, explore ways to enhance coordination among the various mediation initiatives, and recalibrate the AU’s engagement in support of an inclusive, Sudanese-led political dialogue. It would not also be surprising if the issue of the lifting of Sudan’s suspension would arise, more so on account of the fact that it would be one of the issues that the representative of Sudan may likely raise during the informal consultation.

On the same date, the PSC will also receive a briefing on the situation in Somalia, expectedly with a particular focus on the operation and financing of the African Union Support and Stabilisation Mission in Somalia (AUSSOM). At its last meeting, held on 15 December 2025, the PSC considered the report of the Chairperson of the AU Commission, which highlighted key developments in Somalia and progress in the implementation of AUSSOM’s mandate during the period from July to December 2025. The report covered, inter alia, progress towards the operationalisation of the mission, as well as the financial and logistical challenges it continues to face. Against the backdrop of the financial, logistical, operational, and political constraints affecting the mission, the Chairperson of the Commission outlined three options for the PSC’s strategic guidance on the future of AUSSOM. During that session, the Council, instead of pronouncing itself on the proposed options, requested the AU Commission to submit a detailed report elaborating on each option, including their implications for the sustainability of AUSSOM and its operations. The Council further requested the Commission to urgently convene a meeting of AUSSOM TCCs/PCCs at the level of Chiefs of Defence Forces to deliberate on the three options and submit their recommendations for the Council’s consideration. Of immediate interest for the upcoming ministerial session will be to hear from the AU Commission on the PSC’s request for the Commission to fast-track the immediate release of the allocated funds to AUSSOM and to report on its implementation to the next meeting of the Council.’

After the 39th AU Summit, on 19 February, the PSC will hold an open session on Climate, Peace and Security. The last time the PSC held a session on this subject was at its 1301st session of September 2025, which situated the climate-security engagement firmly within the wider climate change policy framework, thereby eschewing the risk of bifurcation between the climate change policy process and the climate, peace and security policy making. Apart from the impact of climate change induced depletion of scarce natural resources on which people depend for their livelihoods including water and pasture on conflicts in the Sahel and Lake Chad Basin, discussions are likely to focus on strengthening evidence-based and conflict-sensitive approaches, mobilising adequate and predictable climate finance for adaptation, loss and damage and a just transition, and advancing the integration of climate indicators into early warning and peace and security mechanisms. The session may also provide an update on progress toward the Common African Position (CAP) on Climate, Peace and Security, including ongoing consultations with AU Member States, the African Group of Negotiators and RECs/RMs, as well as its expected alignment with AU climate frameworks and the Paris Agreement – with finalisation now anticipated ahead of COP31.

On 24 February, the PSC will hold a consultation with the Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO), the World Food Programme (WFP), and the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD) on the nexus between food, peace and security. The session aims to deepen the Council’s understanding of how conflict, climate shocks and food insecurity reinforce one another across the continent. While the PSC has previously addressed food insecurity within its humanitarian agenda, it was at its 1083rd session of 9 May 2022 that the Council explicitly dedicated attention to the link between food security and conflict and requested regular briefings by the AU Commission in collaboration with relevant regional institutions. The discussion is additionally expected to build on issues observed in various conflict settings, including the impact of armed conflict on agricultural production, food systems, displacement and market access, as well as on how food assistance, rural development and resilience-building interventions can contribute to conflict prevention and peacebuilding. FAO is expected to provide technical analysis on food security trends and agricultural systems, WFP will draw on operational data from conflict-affected settings where millions depend on emergency food assistance, and IFAD is expected to highlight long-term investments in smallholder livelihoods and rural resilience in fragile contexts. The urgency of this consultation is underscored by ongoing conflicts such as in Sudan, where violence has driven famine in parts of the country, and in the eastern Democratic Republic of Congo, where sustained insecurity has disrupted farming and supply chains, contributing to acute food insecurity affecting tens of millions.

On 25 February, the PSC is expected to have a field visit. However, not much detail is provided at the time of finalising this edition of Insights on the PSC and going to print.

The month will conclude on 27 February with an informal consultation between the Council and Member States currently in political transition, namely Burkina Faso, Guinea-Bissau, Madagascar, Mali, Niger and Sudan. This will be the fifth such consultation since the PSC institutionalised this format within its working methods following its 14th Retreat on Working Methods in November 2022. Held in accordance with Article 8(11) of the PSC Protocol, the consultations are held to enable direct engagement with representatives of Member States suspended from AU activities due to unconstitutional changes of government. The session will assess progress made and challenges encountered in ongoing transition processes and consider how the PSC can further strengthen its support for the political normalisation of the affected Member States, building on discussions held during the December 2025 session. No formal outcome document is expected.

The PPoW in footnotes also includes the presentation of the Report on the Activities of the PSC for 2025 and the State of Peace and Security in Africa to the AU Assembly. This is expected to happen on 14-15 February during the 39th AU Summit of the Assembly. As per the current practice, Egypt, as Chairperson of the PSSC, will introduce and present a summary followed by a full presentation of the report by the Commissioner for Political Affairs, Peace and Security (PAPS). However and in a commendable working methods improvement, for the first time, the proposed draft agenda of the AU Assembly introduces a different approach that singles out the major conflict situations for a dedicated and focused discussion. These are: a) progress report on the AU mediation in Eastern DRC, b) Situation in Sudan and South Sudan, and c) Situation in the Sahel.

In addition to the foregoing, the PSC’s Committee of Experts (CoE) is scheduled to convene two virtual meetings and one physical meeting during the month. The first virtual meeting, to be held on 5 February, will focus on preparations for the ministerial-level sessions on Sudan and Somalia scheduled for 10 February. The other will be a physical meeting on 20 February to convene the inaugural meeting of the PSC Subcommittee on Post-Conflict Reconstruction and Development (PCRD). The final CoE meeting of the month will be held virtually on 23 February and will feature a briefing by the AU Artificial Intelligence Advisory Group on Governance, Peace and Security.

Monthly Digest on The African Union Peace And Security Council - December 2025

Monthly Digest on The African Union Peace And Security Council - December 2025

Date | December 2025

In December, under the chairship of Côte d’Ivoire, the African Union (AU) Peace and Security Council (PSC) had a scheduled provisional pgramme of work (PPoW) consisting of four substantive sessions covering five agenda items. After the revision of the programme, five sessions were held, covering eight agenda items and an informal consultation with countries in transition, as well as the 12th High-Level Seminar on Peace and Security in Africa.

Africa’s Multilateral Reckoning: Mediation, Leadership, and Survival in 2026

Africa’s Multilateral Reckoning: Mediation, Leadership, and Survival in 2026

Date | 30 January 2026

Abdul Mohammed, Senior Fellow at Amani Africa and Former Senior UN Official and Chief of Staff of AU High-level Panel on Sudan

Multilateralism has never been an inspiring word. It is procedural, abstract, and emotionally thin. No one rallies under its banner, and no leader wins popularity by defending it. Yet for Africa, multilateralism has never been a luxury of orderly times or a matter of institutional aesthetics. It has been, repeatedly and painfully, a strategy of survival. When collective systems fracture or lose authority, Africa is not a marginal casualty of global disorder; it is among the first and hardest hit.

As the continent enters 2026, this reality confronts Africa’s institutions with unusual force. Across the continent—from Sudan and the eastern Democratic Republic of Congo to the Sahel—war is no longer episodic or exceptional. It is increasingly systemic, durable, and profitable. Violence has become a bargaining instrument, fragmentation a political asset, and mediation itself a competitive marketplace. In such conditions, the question confronting Africa’s leaders is no longer abstract: can the continent’s multilateral institutions still exercise authority, or have they become spectators to conflicts they were created to prevent?

This question bears directly on the current leadership of the African Union. There will be no new leadership arriving in 2026. The current leadership, elected in 2025, now confronts its first true test. The coming year will not be a grace period; it will be a reckoning. Africa’s conflicts are deepening, external pressures are intensifying, and the margin for procedural caution is narrowing. The credibility of the present leadership will be judged not by intentions or rhetoric, but by political judgment and action.

Africa enters 2026 institutionally fatigued, politically fragmented, and increasingly exposed to assertive external actors pursuing bilateral advantage at the expense of collective order. The global environment has become harsher: geopolitical rivalry has replaced cooperation, transactional diplomacy has displaced norms, and multilateral restraint is no longer assumed. In this context, the African Union cannot afford leadership that confuses restraint with responsibility or equates neutrality with wisdom.

The challenge before the current leadership is therefore stark. It is not a question of managing institutions, refining processes, or preserving consensus for its own sake. It is a question of whether those at the helm are prepared to exercise authority, take political risks, and defend continental principles when doing so is uncomfortable. Multilateralism, in dark times, is not about convening meetings; it is about drawing lines.

The year 2026 will thus be decisive. If the African Union continues to drift—speaking in careful language while conflicts harden and authority leaks outward—it will confirm a dangerous perception: that Africa’s premier multilateral institution is no longer capable of shaping outcomes. If, however, the current leadership rises to the moment, reasserts political purpose, and treats mediation as an exercise in consequence rather than ceremony, the African Union may yet recover its relevance. The test is immediate, and it cannot be deferred.

On paper, the African Union should be a formidable mediation actor. It possesses peace and security institutions, mediation capacities, and panels of eminent persons. Yet in practice, it has struggled to shape outcomes in the continent’s most consequential conflicts. The problem is not absence of tools, but erosion of authority. Mediation succeeds when norms are backed by leverage and when institutions are willing to impose political costs.

The Union’s recent record in Sudan, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and the Sahel underscores this pattern. In Sudan, early warning and legal authority existed, yet hesitation prevailed as war escalated. In eastern Congo, fragmented initiatives and militarized responses crowded out political solutions. In the Sahel, inconsistent enforcement of norms and reactive diplomacy allowed coups and counter-coups to consolidate. In each case, the vacuum created by African caution was filled by external actors pursuing their own interests.

Looking ahead, Africa’s conflicts increasingly resemble political marketplaces. Loyalty is purchased, fragmentation rewarded, and violence normalized as a negotiating tool. In such environments, moral persuasion alone is insufficient. Norms without leverage are priced out, and multilateralism that avoids imposing costs becomes performative.

The African Union’s comparative advantage is not financial or military. It lies in legitimacy: the ability to confer recognition, set benchmarks, and insist that peace, rights, and governance are inseparable. Reclaiming this role requires a renewal of Pan-Africanism as an intellectual and moral tradition—one that insists on sovereignty as responsibility, not exemption.

If the African Union is to remain relevant in 2026, it must reassert convening authority, enforce coordination, benchmark mediation participation, and place civic legitimacy at the center of peace processes. Above all, leadership must rediscover courage. Unity without principle is not unity; it is abdication.

Africa’s multilateral institutions were never designed to deliver perfection. They were designed to prevent catastrophe. Whether the African Union can rise to this challenge in 2026 will determine not only its own credibility, but Africa’s capacity to navigate an unforgiving world.

This article was first published on Diplomacy Now and can be accessed on https://dialogueinitiatives.org/the-african-unions-biggest-test/

Africa’s Multilateral Reckoning: Mediation, Leadership, and Survival in 2026

Africa’s Multilateral Reckoning: Mediation, Leadership, and Survival in 2026

Date | 30 January 2026

Abdul Mohammed, Senior Fellow at Amani Africa and Former Senior UN Official and Chief of Staff of AU High-level Panel on Sudan

Multilateralism has never been an inspiring word. It is procedural, abstract, and emotionally thin. No one rallies under its banner, and no leader wins popularity by defending it. Yet for Africa, multilateralism has never been a luxury of orderly times or a matter of institutional aesthetics. It has been, repeatedly and painfully, a strategy of survival. When collective systems fracture or lose authority, Africa is not a marginal casualty of global disorder; it is among the first and hardest hit.

As the continent enters 2026, this reality confronts Africa’s institutions with unusual force. Across the continent—from Sudan and the eastern Democratic Republic of Congo to the Sahel—war is no longer episodic or exceptional. It is increasingly systemic, durable, and profitable. Violence has become a bargaining instrument, fragmentation a political asset, and mediation itself a competitive marketplace. In such conditions, the question confronting Africa’s leaders is no longer abstract: can the continent’s multilateral institutions still exercise authority, or have they become spectators to conflicts they were created to prevent?

This question bears directly on the current leadership of the African Union. There will be no new leadership arriving in 2026. The current leadership, elected in 2025, now confronts its first true test. The coming year will not be a grace period; it will be a reckoning. Africa’s conflicts are deepening, external pressures are intensifying, and the margin for procedural caution is narrowing. The credibility of the present leadership will be judged not by intentions or rhetoric, but by political judgment and action.

Africa enters 2026 institutionally fatigued, politically fragmented, and increasingly exposed to assertive external actors pursuing bilateral advantage at the expense of collective order. The global environment has become harsher: geopolitical rivalry has replaced cooperation, transactional diplomacy has displaced norms, and multilateral restraint is no longer assumed. In this context, the African Union cannot afford leadership that confuses restraint with responsibility or equates neutrality with wisdom.

The challenge before the current leadership is therefore stark. It is not a question of managing institutions, refining processes, or preserving consensus for its own sake. It is a question of whether those at the helm are prepared to exercise authority, take political risks, and defend continental principles when doing so is uncomfortable. Multilateralism, in dark times, is not about convening meetings; it is about drawing lines.

The year 2026 will thus be decisive. If the African Union continues to drift—speaking in careful language while conflicts harden and authority leaks outward—it will confirm a dangerous perception: that Africa’s premier multilateral institution is no longer capable of shaping outcomes. If, however, the current leadership rises to the moment, reasserts political purpose, and treats mediation as an exercise in consequence rather than ceremony, the African Union may yet recover its relevance. The test is immediate, and it cannot be deferred.

On paper, the African Union should be a formidable mediation actor. It possesses peace and security institutions, mediation capacities, and panels of eminent persons. Yet in practice, it has struggled to shape outcomes in the continent’s most consequential conflicts. The problem is not absence of tools, but erosion of authority. Mediation succeeds when norms are backed by leverage and when institutions are willing to impose political costs.

The Union’s recent record in Sudan, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and the Sahel underscores this pattern. In Sudan, early warning and legal authority existed, yet hesitation prevailed as war escalated. In eastern Congo, fragmented initiatives and militarized responses crowded out political solutions. In the Sahel, inconsistent enforcement of norms and reactive diplomacy allowed coups and counter-coups to consolidate. In each case, the vacuum created by African caution was filled by external actors pursuing their own interests.

Looking ahead, Africa’s conflicts increasingly resemble political marketplaces. Loyalty is purchased, fragmentation rewarded, and violence normalized as a negotiating tool. In such environments, moral persuasion alone is insufficient. Norms without leverage are priced out, and multilateralism that avoids imposing costs becomes performative.

The African Union’s comparative advantage is not financial or military. It lies in legitimacy: the ability to confer recognition, set benchmarks, and insist that peace, rights, and governance are inseparable. Reclaiming this role requires a renewal of Pan-Africanism as an intellectual and moral tradition—one that insists on sovereignty as responsibility, not exemption.

If the African Union is to remain relevant in 2026, it must reassert convening authority, enforce coordination, benchmark mediation participation, and place civic legitimacy at the center of peace processes. Above all, leadership must rediscover courage. Unity without principle is not unity; it is abdication.

Africa’s multilateral institutions were never designed to deliver perfection. They were designed to prevent catastrophe. Whether the African Union can rise to this challenge in 2026 will determine not only its own credibility, but Africa’s capacity to navigate an unforgiving world.

This article was first published on Diplomacy Now and can be accessed on https://dialogueinitiatives.org/the-african-unions-biggest-test/

Africa’s Multilateral Reckoning: Mediation, Leadership, and Survival in 2026

Africa’s Multilateral Reckoning: Mediation, Leadership, and Survival in 2026

Date | 30 January 2026

Abdul Mohammed, Senior Fellow at Amani Africa and Former Senior UN Official and Chief of Staff of AU High-level Panel on Sudan

Multilateralism has never been an inspiring word. It is procedural, abstract, and emotionally thin. No one rallies under its banner, and no leader wins popularity by defending it. Yet for Africa, multilateralism has never been a luxury of orderly times or a matter of institutional aesthetics. It has been, repeatedly and painfully, a strategy of survival. When collective systems fracture or lose authority, Africa is not a marginal casualty of global disorder; it is among the first and hardest hit.

As the continent enters 2026, this reality confronts Africa’s institutions with unusual force. Across the continent—from Sudan and the eastern Democratic Republic of Congo to the Sahel—war is no longer episodic or exceptional. It is increasingly systemic, durable, and profitable. Violence has become a bargaining instrument, fragmentation a political asset, and mediation itself a competitive marketplace. In such conditions, the question confronting Africa’s leaders is no longer abstract: can the continent’s multilateral institutions still exercise authority, or have they become spectators to conflicts they were created to prevent?

This question bears directly on the current leadership of the African Union. There will be no new leadership arriving in 2026. The current leadership, elected in 2025, now confronts its first true test. The coming year will not be a grace period; it will be a reckoning. Africa’s conflicts are deepening, external pressures are intensifying, and the margin for procedural caution is narrowing. The credibility of the present leadership will be judged not by intentions or rhetoric, but by political judgment and action.

Africa enters 2026 institutionally fatigued, politically fragmented, and increasingly exposed to assertive external actors pursuing bilateral advantage at the expense of collective order. The global environment has become harsher: geopolitical rivalry has replaced cooperation, transactional diplomacy has displaced norms, and multilateral restraint is no longer assumed. In this context, the African Union cannot afford leadership that confuses restraint with responsibility or equates neutrality with wisdom.

The challenge before the current leadership is therefore stark. It is not a question of managing institutions, refining processes, or preserving consensus for its own sake. It is a question of whether those at the helm are prepared to exercise authority, take political risks, and defend continental principles when doing so is uncomfortable. Multilateralism, in dark times, is not about convening meetings; it is about drawing lines.

The year 2026 will thus be decisive. If the African Union continues to drift—speaking in careful language while conflicts harden and authority leaks outward—it will confirm a dangerous perception: that Africa’s premier multilateral institution is no longer capable of shaping outcomes. If, however, the current leadership rises to the moment, reasserts political purpose, and treats mediation as an exercise in consequence rather than ceremony, the African Union may yet recover its relevance. The test is immediate, and it cannot be deferred.

On paper, the African Union should be a formidable mediation actor. It possesses peace and security institutions, mediation capacities, and panels of eminent persons. Yet in practice, it has struggled to shape outcomes in the continent’s most consequential conflicts. The problem is not absence of tools, but erosion of authority. Mediation succeeds when norms are backed by leverage and when institutions are willing to impose political costs.

The Union’s recent record in Sudan, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and the Sahel underscores this pattern. In Sudan, early warning and legal authority existed, yet hesitation prevailed as war escalated. In eastern Congo, fragmented initiatives and militarized responses crowded out political solutions. In the Sahel, inconsistent enforcement of norms and reactive diplomacy allowed coups and counter-coups to consolidate. In each case, the vacuum created by African caution was filled by external actors pursuing their own interests.

Looking ahead, Africa’s conflicts increasingly resemble political marketplaces. Loyalty is purchased, fragmentation rewarded, and violence normalized as a negotiating tool. In such environments, moral persuasion alone is insufficient. Norms without leverage are priced out, and multilateralism that avoids imposing costs becomes performative.

The African Union’s comparative advantage is not financial or military. It lies in legitimacy: the ability to confer recognition, set benchmarks, and insist that peace, rights, and governance are inseparable. Reclaiming this role requires a renewal of Pan-Africanism as an intellectual and moral tradition—one that insists on sovereignty as responsibility, not exemption.

If the African Union is to remain relevant in 2026, it must reassert convening authority, enforce coordination, benchmark mediation participation, and place civic legitimacy at the center of peace processes. Above all, leadership must rediscover courage. Unity without principle is not unity; it is abdication.

Africa’s multilateral institutions were never designed to deliver perfection. They were designed to prevent catastrophe. Whether the African Union can rise to this challenge in 2026 will determine not only its own credibility, but Africa’s capacity to navigate an unforgiving world.

This article was first published on Diplomacy Now and can be accessed on https://dialogueinitiatives.org/the-african-unions-biggest-test/

Commemoration of Africa Day of Peace and Reconciliation

Commemoration of Africa Day of Peace and Reconciliation

Date | 29 January 2026

Tomorrow (30 January), the African Union (AU) Peace and Security Council (PSC) will convene its 1328th session where it will discuss the fourth commemoration of the ‘Africa Day of Peace and Reconciliation and Lessons learnt for the countries in conflict: Experiences of South Africa, Cote d’Ivoire, Sierra Leone, Angola, South Sudan, and the Great Lakes region’ as an open session.

Following the opening statement of the Chairperson of the PSC for the month, Jean-Léon Ngandu Ilunga, Permanent Representative of the Democratic Republic of Congo to the AU, Bankole Adeoye, the Commissioner for Political Affairs, Peace and Security (PAPS), will make a statement. The meeting might feature Domingos Miguel Bembe, Permanent Representative of the Republic of Angola to the AU, who may provide a briefing on Angola’s efforts for peace and reconciliation on the continent, as the AU Champion for Peace and Reconciliation. Other members expected to participate in the session include representatives from South Africa, Cote d’Ivoire, Sierra Leone, Angola, South Sudan, and the Great Lakes region. A representative from the UN may also be present at the meeting.

The 4th Commemoration of the Africa Day of Peace and Reconciliation is set to build on the previous commemorations, and this year’s observance will focus on the practical application of peacebuilding strategies. Given the consideration of ‘Lessons Learnt for Countries in Conflict,’ the open session will specifically analyse the transformative experiences of South Africa, Côte d’Ivoire, Sierra Leone, Angola, South Sudan, and the Great Lakes region. By examining these diverse national trajectories, the PSC will aim to identify proven blueprints for national healing. These experience-sharing is intended to serve as a blueprint for the AU to more effectively intervene in current crises, particularly the devastating war in Sudan and the volatile security situation in the Eastern DRC, reinforcing the continent’s commitment to Silencing the Guns and fostering enduring social cohesion.

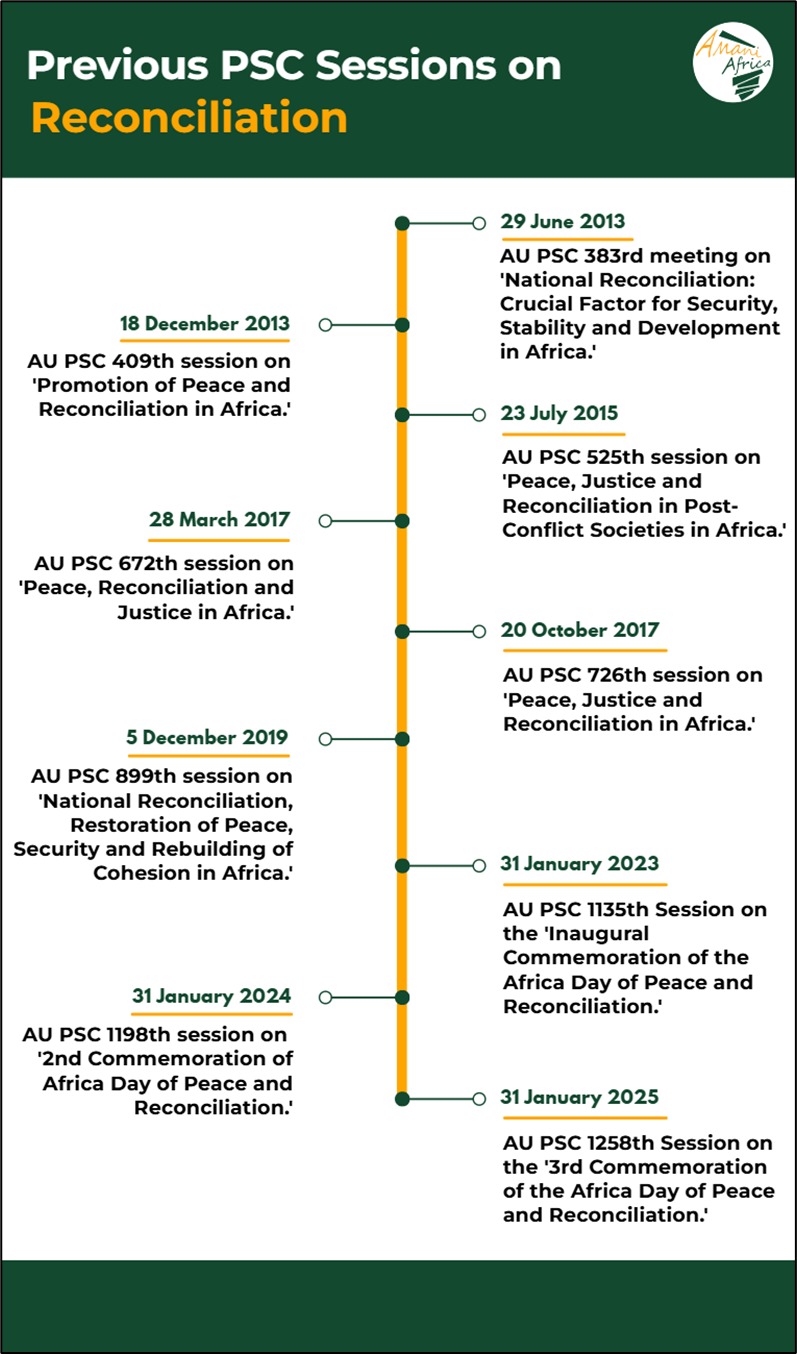

Since its inaugural meeting in 2023, the session has been traditionally held on 31 January of each year, following the declaration of the 16th Extraordinary Session of the AU Assembly on terrorism and unconstitutional changes of government in Africa held in May 2022 in Malabo, Equatorial Guinea, in which it decided to institutionalise the commemoration annually. During the last commemoration, the 3rd, held on 31 January 2025, the PSC called for the ‘domestication of the commemoration of the Africa Day of Peace and Reconciliation at Regional and national level…’ and highlighted the need for ‘the ‘Africa Day of Peace and Reconciliation’ to be aligned with efforts to advance the implementation of the AU Transitional Justice Policy, which provides a roadmap, ensuring that reconciliation is built on accountability, truth-telling, and social cohesion.’

Given this, with lessons learnt, South Africa’s experience, anchored by its Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), offers a profound lesson in choosing restorative justice over retribution. By prioritising the public acknowledgement of truth in exchange for conditional amnesty, the model allowed a fractured nation to transition from apartheid to democracy without collapsing into a cycle of revenge. The Côte d’Ivoire experience, on the other hand, highlights the necessity of moving reconciliation beyond the capital city and into the heart of rural and urban neighbourhoods through local peace initiatives like the UPF-Côte d’Ivoire’s journey over the past two decades in conflict prevention, youth engagement, and community reconciliation. This provides a vital lesson for current conflict zones: for a peace agreement to hold, it must empower community leaders and local peace initiatives to act as mediators, effectively mending the social fabric by fostering face-to-face reconciliation between neighbours who were once divided by conflict.

Sierra Leone’s post-civil war recovery is anchored in the ‘Fambul Tok’ (Family Talk) model, which emphasises that reconciliation must happen at the village level, not just in high courts. Following its 11-year civil war (1991–2002), Sierra Leone adopted a multifaceted approach to recovery by combining judicial accountability with social healing. This strategy centred on the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) and the Special Court for Sierra Leone (SCSL) to address wartime atrocities. Simultaneously, grassroots programmes like Fambul Tok were established to mend the social fabric and promote forgiveness at the community level. In Angola, following the end of its 27-year civil war in 2002, the country has evolved into a prominent regional peacemaker under the leadership of President João Lourenço – the AU’s Champion for Peace and Reconciliation. The nation has prioritised diplomatic mediation, especially regarding the conflict in the DRC. In South Sudan, the peace and reconciliation landscape in 2026 is characterised by a fragile adherence to the R-ARCSS framework. The promise of the 2018 Revitalised Agreement is still alive, yet it is shadowed by relentless local violence. Significant legislative steps have been taken, but the cycle of deadly conflict remains a formidable barrier to lasting reconciliation.

Regional peace and stability in the Great Lakes region hinge on strong cooperation frameworks and inclusive, long-term strategies that address both immediate security threats and deeper structural challenges. Central to these efforts is the Peace, Security and Cooperation Framework (PSCF) for the DRC and the region, alongside the work of the International Conference on the Great Lakes Region (ICGLR), which brings together more than eleven member states to curb conflict and promote development. Yet durable peace cannot be achieved without tackling root causes such as disputes over natural resources, weak governance, and the lingering legacy of violence, particularly in the DRC, Rwanda, and Burundi. National reconciliation initiatives, including Rwanda’s National Unity and Reconciliation Commission and Burundi’s power-sharing arrangements, have sought to rebuild social cohesion and political stability.

In addition, as previously mentioned in the previous commemoration on the importance of further strengthening the Continental Early Warning System and preventive diplomacy on the Continent, it will be imperative that the council addresses this, aligning its deliberations with the ongoing APSA review and reform process. By linking these reforms to the peace, security, and development nexus, the PSC must encourage Member States to look beyond immediate security interventions and instead redouble efforts to address the deep-seated structural root causes of violence. This involves a holistic commitment to fixing governance-related factors – such as political exclusion and socio-economic inequality – ensuring that the AU’s reformed peace architecture is equipped not just to silence guns, but to prevent them from being fired in the first place.

The meeting is expected to result in a communiqué. The PSC is expected to welcome the 4th Commemoration of Africa Day for Peace and Reconciliation and call for the need to continue promoting the culture of peace, tolerance, justice, forgiveness, and reconciliation as an important step for conflict prevention, especially in post-conflict communities. Council is also likely to acknowledge the role of President João Manuel Gonçalves Lourenço, of Angola, as the AU Champion for Peace and Reconciliation, applauding his efforts to promote peace and reconciliation and his efforts to galvanise support for peace initiatives across the region. Council may also highlight the important role of national reconciliation towards achieving the AU’s noble goal of Silencing the Guns by 2030, considering the critical role that reconciliation plays in preventing conflict relapse and laying a strong foundation for sustainable peace in countries emerging from violent conflicts. It will also be important for the PSC to underscore the importance of inclusive and transparent political transitions, and emphasise the need for comprehensive peace, reconciliation, and development initiatives across the continent.