Annual Consultative Meeting between the Peace and Security Council (PSC) and the Pan-African Parliament (PAP)

Annual Consultative Meeting between the Peace and Security Council (PSC) and the Pan-African Parliament (PAP)

Date | 16 July 2025

On July 17 & 18, the African Union (AU) Peace and Security Council (PSC) is expected to convene a two-day session dedicated to the annual joint consultative meeting with the Pan-African Parliament (PAP) in Midrand, South Africa.

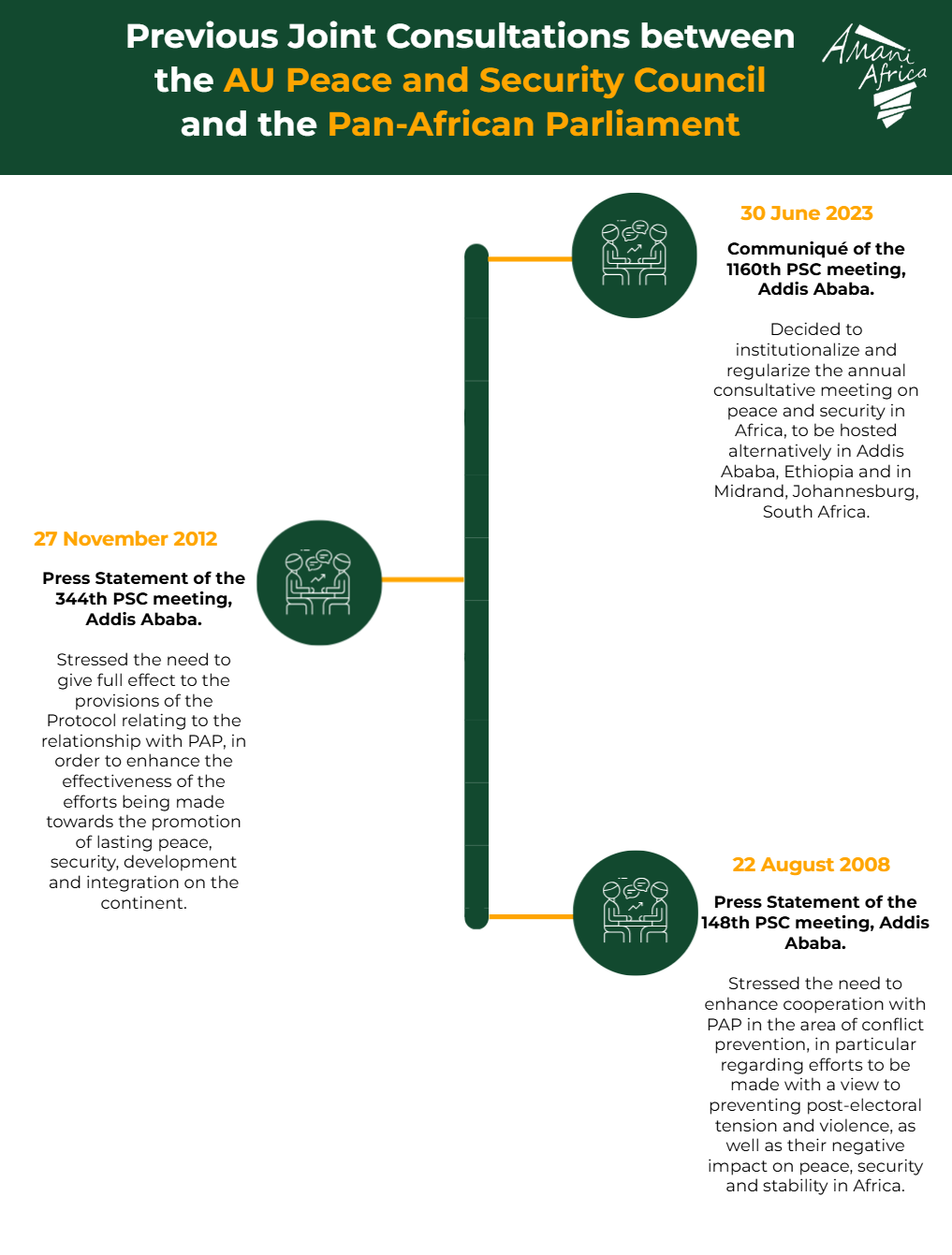

The consultative meeting is expected to be co-chaired by the President of the PAP and the Chairperson of the PSC. This will be the fourth meeting being held within the framework of Article 18 of the PSC Protocol.

The session will commence with opening remarks to be delivered by Rebecca A. Otengo, Permanent Representative of Uganda to the AU and Chairperson of the PSC for July, and Chief Fortune Charumbira, the President of the PAP. It is expected that this will be followed by an address by Bankole Adeoye, the AU Commissioner for Political Affairs, Peace and Security.

Although it is not being held on time as previously decided, the consultative meeting is being held in accordance with the outcome of the last consultative meeting of the two bodies held in June 2023, contained in the 1160th Communiqué of the PSC. Most particularly, the two bodies committed to to institutionalise and regularise the annual consultative meeting, between the PSC and PAP, on peace and security in Africa to be hosted alternatively in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia and in Midrand, Johannesburg, South Africa and, in this respect, decide[d] that the next annual consultative meeting will be held in June 2024, in Midrand, Johannesburg, South Africa. Since the meeting was not held in 2024 as per the terms of the communiqué of the 1160th session, tomorrow’s meeting is accordingly being held in Midrand, Johannesburg, hosted by the PAP.

The holding of the session is preceded by a preparatory meeting. Apart from the usual preparatory work of the PSC Committee of Experts, recently, on the sidelines of the AU Mid-Year Coordination Meeting (MYCM) in Malabo, Equatorial Guinea, the two bodies held a high-level preparatory meeting to set the stage for their Joint Consultative Meeting.

Tomorrow’s session is being held in accordance with the legal instruments that set out the mandate of the two bodies. First and most importantly, Article 18 of the PSC Protocol stipulates that the PSC establishes a close working relationship with the PAP, recognising the complementarity of their respective roles in the promotion of peace, security, stability, human rights and democratic governance in Africa. Second, this consultative session also draws on the core objectives of the PAP, which, as stated in the 2001 Protocol to the Treaty Establishing the African Economic Community Relating to the PAP, cover the promotion of peace, security, stability, human rights and democratic governance. Additionally, the PAP is invested with the role of receiving reports from the PSC. Article 18 (2) and (3) of the PSC Protocol require the PSC to submit reports to the PAP through the AU Commission Chairperson whenever requested.

The consultative meeting is expected to have two dimensions. The first dimension is expected to involve exchange between the two bodies on the state of peace and security, as well as democratic governance in Africa. This exchange is expected to draw on the address by Adeoye. Within this framework, it will not be surprising for the deliberation to focus, among others, on the various conflict situations and the peace and security issues on the agenda of the PSC. These may include conflict hotspots, including the Sahel, the Horn of Africa (Sudan, Somalia and South Sudan), Eastern DRC and thematic issues such as countries in transition, unconstitutional changes of government, terrorism and the AU’s engagement in advancing the reform of the multilateral system. As the first vice-president of PAP indicated during the preparatory meeting, the meeting is also expected to engage on the need to include women and youth in continental fora focusing on peace, security and governance.’ In this context, the issue of children affected by armed conflict (CAAC) is expected to receive particular attention, drawing on the focus given to it in the program of work of the PSC for the month and the role of the PSC Chairperson as Co-Chairperson of the Africa Platform on CAAC.

The second dimension of the meeting is expected to address working methods and modalities in operaitonalising Article 18 of the PSC Protocol. The development of the working methods in the relationship between the two concerns the follow-up to commitments made in previous meetings. It is worth recalling in this context that the PSC in the communiquéof its 1160th meeting on the previous consultative meeting underscored ‘the need for the two organs to continue to explore piratical means and way of further enhancing their collaboration and cooperation in the promotion of peace and security as well as African common positions on peace and security matters, particularly, in the international fora.’ It is expected that the PAP would put forward specific proposals on modalities for a close working relationship, as it did during the consultative meeting preceding the last one held during the 344th session of the PSC. Underscoring ‘the importance of building durable working methods,’ at the time of the preparatory meeting held in Malabo, the President of PAP proposed the following modalities: ‘formation of specialised parliamentary committees to support peace and security hotspots; enhanced use of parliamentary diplomacy in conflict resolution and management; institutional and operational synergies backed by time-bound action plans; and consideration of technical and financial capacity-building for PAP’s engagement in peace efforts.’

Tomorrow’s meeting will be held under the theme, ‘Enhancing Institutional Synergy and Collaboration for Sustainable Peace and Security in Africa.’ As such, in addition to the foregoing modalities, it is expected that the exchange will also focus on establishing mechanisms to enhance the PAP’s advocacy role in implementing AU peace and security initiatives.

In the communiqué of its 1160th session on the last consultative meeting, the PSC also requested ‘the PAP to regularly engage with it on its initiatives on the promotion of peace and security and democracy and good governance.’ There is no data to indicate that the PAP took on this invitation and engaged the PSC. Indeed, the report of PAP to the AU policy organs on its activities for 2024, other than the use of vague language of PAP engaging in fostering ‘collaboration on governance and security with AU and peace institutions,’ does not contain that the PAP engaged the PSC. The only notable engagement on peace and security contained in the PAP report is a reference to a resolution on peace and security in Africa and a recommendation on peace and security in Africa.

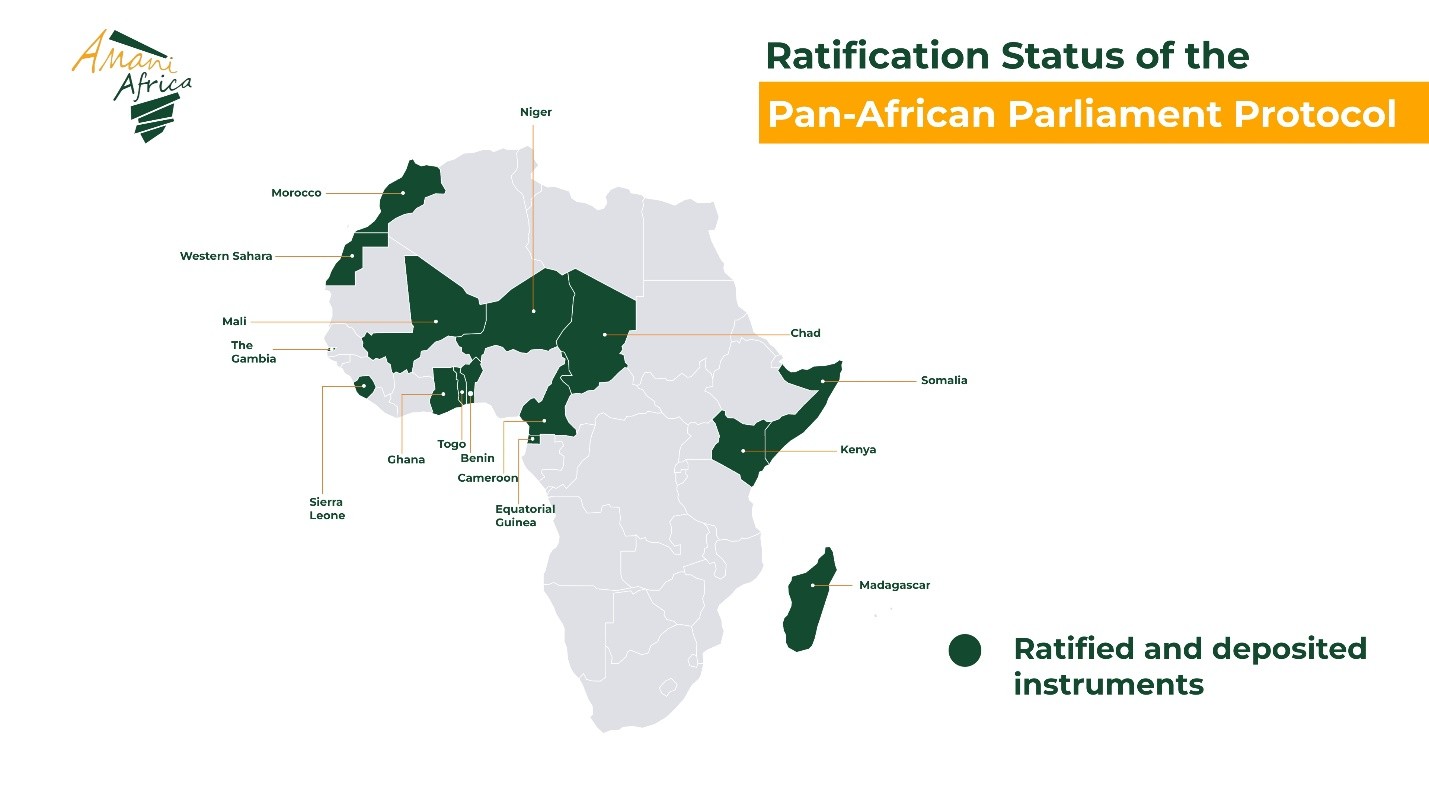

It clearly emerges from the foregoing that, notwithstanding, the solid legal foundation and the potential for a close working relationship, both the legal provisions and the potential remain unrealised. This is in no small part due to the governance and institutional challenges that have afflicted the PAP over the years. Apart from tarnishing the image and public standing of the continental body, PAP’s governance problems and the resulting institutional instability, including the controversy over the appointment of the clerk of PAP and the procedure followed in suspending the appointment, have had a direct bearing on the conduct of the activities of the institution. There is also the issue of the lack of ratification of the 2014 Protocol to the Constitutive Act of the AU Relating to the Pan-African Parliament (the 2014 PAP Protocol), which designates the PAP as the legislative body of the AU. The status of signature and ratification did not change from the analysis we produced on the last consultative meeting in June 2023, which put States that signed at 22 and those who deposited the instrument of ratification at 14. While the PSC in the communiqué of its 1160th session on the last consultative meeting held encouraged member states to ratify the protocol in order to enable it to enter into force, the recurring governance issues at PAP do not give confidence to member states on the wisdom of speeding up the entry into force of the protocol.

As such and in the face of the serious peace and security challenges on the continent that require the best performance of all AU institutions, it would be of interest to PSC members to ensure that the consultative meeting does not end up being an exercise in ticking boxes and that PAP organises and conducts itself for delivering on its role in advancing peace, security and stability and democratic governance in Africa. This necessitates not only the articulation of practical modalities for harnessing the mandate of the PAP but also the provision of mutual accountability in delivering on their common mandate.

Similarly, the proper functioning of the PAP would also facilitate the presentation on an annual basis by the Chairperson of the AU Commission on the state of peace and security within the framework of Article 18 (2) & (3) of the PSC Protocol. Since this is a mutual responsibility, the PSC in its 1160th communiqué encouraged the AU Commission to enhance its engagement and continue to work closely with the PAP towards the implementation of these provisions.

The expected outcome is a joint conclusion identifying key areas for collaboration, to be adopted by the PSC as a Communiqué at a later session. It is expected that the PSC and PAP would resort to a unanimous roadmap for structured engagement between the two. In this regard, the two bodies would chart down thematic areas of engagement, including, but not limited to, youth in peacebuilding, climate security, women in peace processes, among others, in order to foster collaboration. It is also expected that the PSC would commend the AU Commission for the renewed efforts to enhance its engagements with PAP and stress the need for the AU Commission to continue to work closely with the Parliament. The outcome is also expected to reiterate the decision of the previous consultative session on institutionalising and regularising the annual consultative meeting and commits to holding the next meeting in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. It is also expected to highlight and welcome the need for ensuring proper functioning of the PAP as a necessary condition for ensuring that the PAP effectively executes its mandate towards contributing to peace and security and democratic governance in Africa, working in collaboration with the PSC. Given the capacity issues clearly stated by the PAP President, the joint conclusions may also highlight the imperative of strengthened capacity of PAP both in terms of the role of its Committees on Cooperation, International Relations and Conflict Resolution and the use of parliamentary diplomacy by the PAP to advance conflict prevention, management and resolution.

Le Conseil de Paix et de Securite de l'Union Africaine - Manuel 2024

Amani Africa

2024

REMERCIEMENTS

Le Manuel du Conseil de paix et de sécurité de l’Union africaine est une initiative d’Amani Africa Media and Research Services (Amani Africa), qui fournit des informations et des analyses faisant autorité sur le CPS et son travail. Comme pour les deux éditions précédentes du Manuel, la présente édition du Manuel a bénéficié de l’engagement d’Amani Africa avec les acteurs clés du travail du CPS. Je tiens à remercier les membres du CPS, en particulier les présidents mensuels du CPS, les Secrétariats du CPS et les membres du Comité d’experts pour leur soutien à la préparation de cette troisième édition du Manuel.

Je tiens à remercier tout particulièrement S.E. Bankole Adeoye, Commissaire aux Affaires politiques, la Paix et la Sécurité (PAPS) pour avoir honoré le présent manuel d’un avant-propos, soulignant l’importance de la recherche et de l’analyse pour soutenir la mise en œuvre du Protocole relatif à la création du CPS.

Permettez-moi également de reconnaitre avec appréciation le soutien habituel du personnel du Secrétariat du CPS, en particulier Neema Nicholaus Chusi, chef par intérim du Secrétariat du CPS.

La présente édition du Manuel est le produit de l’engagement d’Amani Africa avec l’ensemble du personnel du Département du PAPS à qui nous exprimons également notre gratitude.

Nous tenons à remercier le Gouvernement de la Suisse qui a apporté son soutien en tant que partenaire au projet de mise à jour et de publication de cette nouvelle édition du Manuel.

Dr. Solomon Ayele Dersso, au nom de l’équipe d’Amani Africa

Read Full Document

From estrangement to engagement: PSC and ECOWAS MSC call for a cooperation framework for engaging AES States

From estrangement to engagement: PSC and ECOWAS MSC call for a cooperation framework for engaging AES States

Date | 9 July 2025

The severance of ties by the Alliance of Sahel States (AES)—Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger— from the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), marking a watershed moment in the deterioration of solidarity (as former AU Commission Chairperson aptly put it) and regional integration, was top on the agenda of the 16 May 2025 Second Annual Joint Consultative Meeting convened between the African Union (AU) Peace and Security Council (PSC) and the ECOWAS Mediation and Security Council (ECOWAS MSC).

The outcome of the consultation was adopted as a joint communiqué. It is of significance that the consultative meeting reaffirmed the principles of the PSC Protocol, including, most notably, the ‘primary responsibility of the AUPSC in the promotion of peace, security and stability in Africa.’ The meeting also recalled Article 16 of the PSC Protocol, the 2008 MoU and the 2020 Revised Protocol on Relations between the AU and RECs.

It emerges from the outcome of the consultation that the deliberation, not surprisingly, touched on a wide range of issues. Of these, those that are of substantive significance and deserving of particular attention include the threat of terrorism and the democratic governance deficit afflicting the sub-region. In this respect, the two sides expressed deep concern over ‘the worsening insecurity resulting from the spread of terrorism and violent extremism in West Africa, particularly, in the Sahel region, with potential expansion to the littoral states’ and ‘the slow pace of transition in Burkina Faso, Guinea, Mali and Niger.’

While the two Councils were on target in addressing the democratic governance deficit and adherence to governance norms of the AU and ECOWAS, ‘especially in relation to the principle of zero-tolerance of unconstitutional changes of government,’ the lack of reference to some of the significant manifestations of the democratic governance deficit beyond coups makes the call hallow. Apart from coups the region has also experienced in the past years the abuse of electoral processes as experienced in Senegal (See concern expressed by AU Commission in this respect here) and Sierra Leone (here and here) leading to political instability in both countries (with AU, ECOWAS and Commonwealth launching mediation in Seirra Leone) and the disregard of constitutional rules of separation of powers and checks and balances as in Guinea Bissau and manipulation of nationality laws and term limits in Cote d’Ivoire. The lack of reference to these forms of the democratic governance deficit creates a credibility gap, as the AU and ECOWAS express zero tolerance for military coups while failing to clearly pronounce themselves on flawed or rigged elections and the extension of constitutional term limits.

Concerning the persisting threat of conflicts involving terrorist groups particularly in the Sahel, the PSC and the ECOWAS MSC agreed ‘to develop a security cooperation framework involving the AU and ECOWAS for engagement with Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger, to more effectively address insecurity in the West Africa Region.’ Given how conflicts involving terrorist groups have been ravaging these central Sahel countries for more than a decade, the fact that such a mechanism was instituted only in 2025 is reflective of the lack of proactiveness of the continental and sub-regional bodies. Even then, the test of this decision depends on the proverbial pudding of implementation. In this respect, one of the significant issues that the AU and ECOWAS need to address, apart from ensuring follow-through, is rebuilding trust with the three central Sahel states. Considering that the three Sahelian states are pursuing their regional integration processes and announced the building of the Alliance of Sahelian States’ (AES) 5,000-member joint force, the success of the planned engagement with these states (including the joint framework for addressing the threat of terrorism) depends also on building on and accommodation of these efforts.

Acknowledging the poor delivery of existing policy responses, the PSC and ECOWAS MSC also stressed ‘the need for reinvigorating the Nouakchott Process, the ECOWAS Plan of Action Against Terrorism, the Accra Initiative, the Multinational Joint Task Force (MNJTF) and PSC comm.1275 on a combined maritime taskforce for addressing piracy in the Gulf of Guinea.’(emphasis added) They also highlighted the need for addressing exogenous factors that accentuate the threat, such as ‘the supply of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs)’ and ‘small arms and light weapons’ as well as ‘the influx of mercenaries and foreign fighters.’ The next step is for the AU and ECOWAS to work on specific modalities of addressing these ‘exogenous factors’ or drivers of insecurity in the region, including by updating the 2014 AU Sahel Strategy.

As part of the effort to bolster joint action to address the terrorism menace in the sub-region, the two Councils called for the establishment of a ‘Joint Threat Fusion and Analysis Cell as part of the proposed AU-ECOWAS Counter-Terrorism Coordination Platform, with the African Union Counter Terrorism Centre (AUCTC) designated as the continental coordination point.’ Additionally, the emphasis on the need to review and update the dated AU legal instruments (such as the 1999 Convention on the Prevention and Combating of Terrorism and its 2004 Protocol) is timely, to ensure that these instruments address some of the new dimensions, including, most notably, technology and transnational networks.

Although the communiqué advances APSA and AGA objectives, particularly through Continental Early Warning System (CEWS) and the ECOWAS Early Warning and Response Network (ECOWARN) and counterterrorism efforts, its effectiveness requires complementing these mechanisms with instruments such as the Country Structural Vulnerability and Resilience Assessment (CSVRA) and a revised and updated version of the 2014 AU Sahel Strategy. The AU and ECOWAS can use the revision and updating of this 2014 strategy, which has so far been dormant, as a platform for advancing policy coherence and joint action in their engagement with AES states.

The communiqué directly addressed the withdrawal of AES states from ECOWAS on 29 January 2025, expressing ‘deep concern’ and urging the three states to ‘reconsider’ their decision. Yet, considering the lack of follow-up on the previous call of the PSC, their reiteration of the need to ‘continue engaging’ with the AES countries does not inspire confidence that it will lead to any breakthrough. This is in part due to the lack of recognition of addressing the concerns of the AES states. Additionally, beyond the critical role of the leaders of Ghana, Senegal and Togo, the lack of implementation of previous PSC decisions casts serious doubt on the effectiveness of this call to ‘continue engaging.’ The fact that AU neither deployed effective mechanisms nor ensured the effective functioning of existing ones prompted the PSC during its 1212th session to reiterate its request for the AU Commission ‘to appoint a High-Level Facilitator at the level of sitting or former Head of State to engage with the Transitional Authorities.’ Additionally, taking note of ‘the leadership vacuum within the African Union Mission for Mali and Sahel (MISAHEL),’ the PSC requested ‘the Chairperson of the AU Commission to ensure the nomination of a High Representative, which remains a crucial interface in ensuring collective oversight between the Commission, Council, and the Countries in transition.’ The position has been vacant since the departure of Maman Sambo Sidikou in August 2023.

The call by the PSC and the ECOWAS MSC for a cooperation framework to engage AES states signals a change from a policy of passive estrangement to one of active engagement. The success of this policy shift, however, depends on another shift from policy statement to action through effective follow-through and a dedicated mechanism for sustained diplomacy.

Consideration of the AU Commission Report on Elections in Africa for the Period of Jan - June 2025

Consideration of the AU Commission Report on Elections in Africa for the Period of Jan - June 2025

Date | 3 July 2025

Tomorrow (4 July), the African Union (AU) Peace and Security Council (PSC) will convene its 1288th Session to consider the mid-year report of the Chairperson of the AU Commission on elections in Africa, covering the period between January and June 2025.

Following the opening statement of the Chairperson of the PSC for the month, Rebecca Otengo, Permanent Representative of Uganda to the AU, Bankole Adeoye, the Commissioner for Political Affairs, Peace and Security (PAPS), is expected to present the report. Statements are also expected from the representatives of Member States that organised elections during the reporting period.

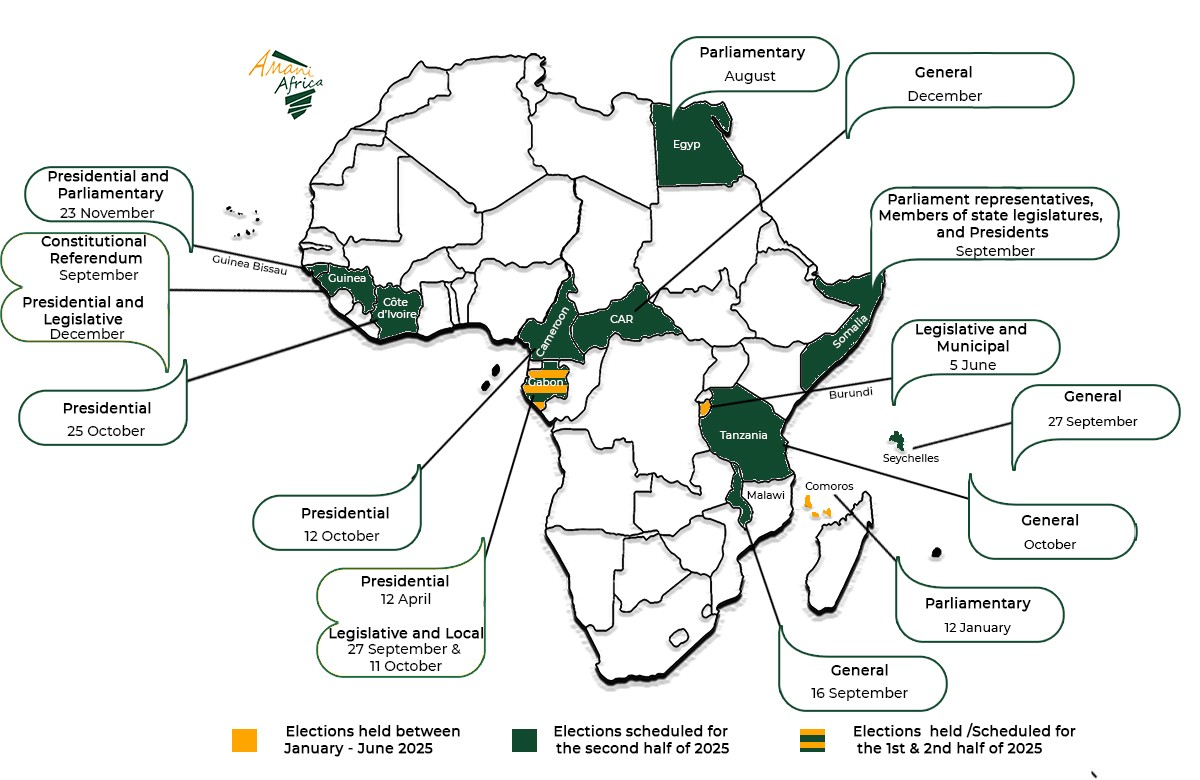

As per the PSC’s decision from its 424th session in March 2014, which mandates periodic updates on African electoral developments, the Chairperson presents a mid-year elections report. The previous update was delivered during the 1255th PSC session on January 24, 2025, and covered electoral activities from July to December 2024. Tomorrow’s briefing will similarly provide accounts of elections conducted from January to June 2025 – covering elections held in Burundi, Comoros and Gabon –while also outlining the electoral calendar for the second half of 2025.

The parliamentary elections held in Burundi on 5 June resulted in a sweeping victory for the ruling National Council for the Defence of Democracy-Forces for the Defence of Democracy (CNDD-FDD) party, which secured all 100 contested seats in the national assembly with 96.5% of the vote. The AU deployed an Election Observation Mission led by Vincent Meriton, former Vice President of Seychelles, comprising 30 observers. In its preliminary report, the mission noted that the elections occurred in a generally stable socio-political and peaceful security environment. However, the mission also reported that some political parties and candidates expressed concerns about biased coverage by public media, alleging it disproportionately favoured the ruling party. Operational challenges were also observed, including complaints from voters in certain areas who did not receive their voter cards. Additionally, opposition parties criticised the elections as undemocratic, citing the systematic harassment and exclusion of opposition groups, particularly the National Congress for Liberty (CNL).

Similarly, the Comoros held parliamentary elections on 12 January. According to the Independent National Election Commission, the ruling Convention for the Renewal of the Comoros (CRC), led by President Azali Assoumani, won a strong majority, securing 28 out of 33 seats. However, several opposition parties rejected the results, citing widespread irregularities and a lack of transparency. These concerns prompted the Supreme Court to annul the outcomes in four constituencies, leading to reruns held later in January. Voter turnout stood at 66.3%, slightly lower than the 70.9% recorded in the 2020 election.

On 12 April 2025, Gabon held a presidential election in which General Brice Oligui Nguema, the interim president and leader of the August 2023 military coup that ousted President Ali Bongo, was a candidate. He was later declared the winner, securing over 90 % of the vote. Voter turnout reached 70.4%, a significant rise compared to the 56.65% recorded in the disputed August 2023 elections.

The AU deployed an Election Observation Mission to Gabon led by Trovoada Patrice, Former Prime Minister of São Tomé and Príncipe, and supported by Domitien Ndayizeye, former President of Burundi and member of the AU Panel of the Wise. Following the election, during its 1277th session, the PSC welcomed the ‘successful’ conduct of the election without addressing the lack of compliance with Article 25(4) of the African Charter on Democracy, Elections and Governance (ACDEG). As highlighted in an analysis featured on Amani Africa’s Ideas Indaba, the PSC’s failure to express its continuous commitment to Article 25(4) while recognising the election outcome in Gabon as marking the return of constitutional order can be interpreted by militaries across the continent that ‘a coup has once again become a viable avenue for ascending to power with the possibility of it being recognised by the AU following the coup’s legitimisation through elections.’ Not surprisingly, the AU appears to be on a path to accord Guinea the same treatment that it accorded Gabon, deepening concerns about the political viability and legitimacy of AU’s norm on non-eligibility of perpetrators of coups, as provided for in Article 25(4) of ACDEG.

Furthermore, the report is also expected to highlight eleven upcoming elections scheduled between July and December 2025, including those in Cameroon, the Central African Republic, Côte d’Ivoire, Egypt, Gabon, Guinea-Bissau, Guinea, Malawi, the Seychelles, Somalia, and Tanzania.

Cameroon’s presidential election on October 5 takes place amid the prospect of President Paul Biya seeking an unprecedented eighth term, having held power since 1982. Biya, aged 92, remains the longest-serving African president, enabled by a 2008 constitutional amendment removing term limits.

The Central African Republic’s (CAR) upcoming elections in December 2025—covering presidential, legislative, and local levels—are set to take place in a politically and security-fragile environment. President Faustin-Archange Touadéra, who is eligible to run again after a controversial 2023 constitutional referendum that eliminated presidential term limits, remains a central figure amid ongoing concerns over democratic backsliding. According to a recent press release by the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), the National Elections Authority (ANE) is facing serious institutional and operational challenges that threaten the timely and credible organisation of the elections. These include internal dysfunction, funding gaps, delays in finalising the electoral roll, and logistical setbacks. In response, the UN is calling for urgent reforms to the electoral authority and the allocation of adequate resources to safeguard the integrity of the elections.

Côte d’Ivoire’s upcoming presidential election in October 2025 is unfolding in a tense and uncertain political climate, with President Alassane Ouattara facing multiple challengers. Recent reports indicate that the electoral landscape is marred by the exclusion of major opposition figures through legal and administrative means. Tidjane Thiam, leader of the main opposition party (PDCI), was removed from the voter roll due to a court ruling that his past French citizenship invalidated his Ivorian nationality, despite his recent renunciation of his French citizenship. Similarly, former President Laurent Gbagbo, Charles Blé Goudé, and exiled former Prime Minister Guillaume Soro remain barred from running in the elections. The Independent Electoral Commission has confirmed that the voter list will not be revised ahead of the October 25 presidential election, effectively excluding these key opposition leaders from participation. Due to these recent developments, Ivorians are taking to the streets to rally for banned opposition figures.

Guinea-Bissau’s presidential and legislative elections, initially scheduled for late 2024, were postponed by President Umaro Sissoco Embaló in November 2024, citing logistical and financial hurdles—a decision that, in the context of the unilateral dissolution of parliament, occasioned a constitutional crisis, triggering criticism from the opposition as unconstitutional. And, when Embaló’s term in office expired in February 2025, he got the Supreme Court extending it to September 2025. Amid constitutional and democratic backsliding and rising contestation by the opposition of Embaló’s legitimacy and delays in elections, a new election date was set for 23 November 2025, following controversial consultations.

Guinea’s military junta, led by General Mamadi Doumbouya, has rescheduled presidential and legislative elections for December 2025, following a constitutional referendum planned for September. This comes after missing the initial December 2024 transition deadline. A new Directorate General of Elections has been established to oversee the process, but the transition plan is facing criticism over transparency, funding, and delays. Concerns persist about the credibility of the elections, as the junta has dissolved over 50 political parties, restricted media, and curtailed political freedoms. The tense political climate and continued repression have fueled opposition protests and scepticism about the inclusiveness of the upcoming elections.

Malawi’s general elections, set for 16 September 2025, are expected to be highly competitive, featuring presidential, parliamentary, and local government races. This will be the second election held under the 50+1 majority system, introduced after the annulment of the 2019 polls. Incumbent President Lazarus Chakwera is seeking re-election but faces strong challenges from former presidents Peter Mutharika and Joyce Banda. Over 7 million voters have registered, with women making up 57% of the electorate. The Malawi Electoral Commission has launched voter registration and preparations under the theme ‘Promoting Democratic Leadership Through Your Vote.’ The African Union has deployed Technical Assistance Missions and a Pre-election Assessment Mission to monitor the process and provide support.

Seychelles’ presidential and legislative elections are scheduled for 27 September, pending final approval of a constitutional amendment establishing fixed election dates. President Wavel Ramkalawan, who won a historic victory in 2020, ending four decades of dominance by the United Seychelles party, is running for a second term with Vice President Ahmed Afif as his running mate. Ramkalawan’s main challenger is Dr. Patrick Herminie of United Seychelles.

Tanzania’s upcoming presidential and legislative elections in October 2025 are expected to be dominated by the ruling Chama Cha Mapinduzi (CCM) party, with President Samia Suluhu Hassan positioned as the clear frontrunner. CCM has officially nominated Hassan for the Union presidency and Hussein Ali Mwinyi for the Zanzibar presidency. The main opposition party, CHADEMA, led by Tundu Lissu, has been barred from the race after refusing to sign a mandatory electoral code of conduct, effectively removing a major challenger. While smaller parties such as ACT-Wazalendo remain in the race, CCM faces minimal opposition. In preparation for the elections, the African Union conducted a pre-election assessment mission in June 2025 to evaluate Tanzania’s institutional readiness, the political climate, and efforts to promote women’s political participation.

Additionally, legislative and local elections are scheduled to be held in Gabon on 27 September and 11 October. Meanwhile, Egypt’s parliamentary elections are scheduled to take place from July 3 to July 10. Although specific dates have not yet been announced, Somalia is also expected to hold parliamentary elections for both federal parliament representatives and state legislatures later this year.

The Chairperson’s report is also expected to highlight key governance trends in Africa. As the January 2025 Monthly digest on the PSC noted, the trend is characterised by a mix of some democratic progress and increasing poor quality of and public confidence in elections. Despite elections becoming common, concerns remain over democratic backsliding, where incumbents manipulate institutions to maintain power, as the examples of Guinea-Bissau or Côte d’Ivoire show. Additionally, upcoming elections in countries such as Guinea, Cameroon, Côte d’Ivoire, and the CAR will pose significant tests to the resilience of national institutions and the AU’s capacity to engage in preventive diplomacy amid heightened security and political tensions.

The expected outcome is a communiqué. The PSC may commend Member States for the peaceful and transparent conduct of elections held between January and June 2025. It may particularly welcome the cooperation extended by these Member States to AU Election Observation Missions and encourage the full implementation of recommendations aimed at deepening democratic gains. In line with its previous decisions, the PSC may acknowledge the progress made by Gabon in transitioning toward a constitutional order. Concerning countries undergoing transition, the Council is expected to encourage them to work closely with the AU Commission. In this regard, the PSC may urge the Commission to continue extending its support to transitional countries in line with relevant AU instruments. In light of upcoming elections during the second half of 2025, the PSC may encourage Member States to invite AU observers, undertake necessary electoral reforms, and uphold national and continental legal frameworks governing elections. It may emphasise the importance of restraint and responsibility among all stakeholders to ensure peaceful, credible, and inclusive electoral processes.

Monthly Digest on The African Union Peace And Security Council - May 2025

Monthly Digest on The African Union Peace And Security Council - May 2025

Date | May 2025

In May, under the Chairship of Sierra Leone, the African Union (AU) Peace and Security Council’s (PSC) Provisional Program of Work (PPoW) for the month provided for the convening of five substantive sessions and a field mission to the Republic of Guinea. Following two revisions to its PPoW, the PSC held four sessions and undertook the mission.

While three of the sessions focused on thematic issues, one session focused on a country-specific situation. All of the sessions were convened at the ambassadorial level.

Update on the situation in Somalia and AUSSOM operations

Update on the situation in Somalia and AUSSOM operations

Date | 2 July 2025

Tomorrow (3 July), the African Union (AU) Peace and Security Council (PSC) will convene its 1287th session at the ministerial level to receive an update on the situation in Somalia and the operations of the AU Support and Stabilisation Mission in Somalia (AUSSOM).

The session is expected to commence with opening remarks by Uganda’s Minister of Foreign Affairs and Chair of the PSC for July 2025, General Jeje Odongo, followed by an introductory statement from the Chairperson of the AU Commission, Mahmoud Ali Youssouf. The Minister of State for Foreign Affairs of Somalia, Ali Mohamed Omar, as well as representatives from the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD), the United Nations (UN) and European Union (EU), are also expected to deliver statements.

Tomorrow’s ministerial meeting comes as the timeline for the completion of the transition from ATMIS to AUSSOM came to an end on 30 June 2025. The last briefing to the PSC on AUSSOM operations took place during its 1276th session, held on 29 April. It focused on ongoing efforts towards the operationalisation of the mission. During that session, the PSC endorsed the Troop and Police Contributing Countries (T/PCCs) for AUSSOM, along with the breakdown of the contribution of each T/PCC. The PSC also called on the T/PCCs and the Federal Government of Somalia (FGS), in coordination with the AU Commission, to finalise the necessary steps for the full and expeditious deployment of the mission.

As 30 June marked the end of Phase I of the mission, during which all AU troops were envisaged to transition from ATMIS to AUSSOM, a major development likely to be highlighted by the AU Commission is the negotiation on the Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) with Troop/Police Contributing Countries (T/PCCs). Pending the finalisation of the signing of the MoU and Status of Force Agreement as well as the completion of ‘the AU and UN procedures to expediate the deployment of Egyptian troops,’ Burundian troops and Ghana’s Formed Police Unit (FPU), as well as the Sierra Leone FPU would need to remain. PSC is expected to extend the timeline for the repatriation of Burundian troops and Ghanaian FPUs as well as the relocation of Sierra Leon’s FPUs.

The session is also expected to follow up on the outcome of the Kampala Summit of Troop Contributing Countries (TCCs) on 25 April 2025. It is to be recalled that the TCCs Summit underscored the need to augment AUSSOM troop strength of 11,146 by at least 8,000 through a bilateral arrangement to address the deteriorating security situation in Somalia. The summit also endorsed the proposal for enhancing air assets and capabilities, as well as strengthening Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance (ISR).

The outcome of the Kampala Summit illustrates the gap between what is required for the effective functioning of AUSSOM and the achievement of its mandate on the one hand and the ‘operational shortfalls’ and the financing gaps facing the mission. While the Summit reiterated that ‘the best solution to adequate, predictable and sustainable funding is the application of the UNSC Resolution 2719 (2023) on Somalia,’ the lack of support from the US meant that this option could not be applied for funding AUSSOM. On 12 May 2025, the UN Security Council failed to authorise the activation of Resolution 2719, even in the hybrid format proposed by the UN Secretariat on the basis of Resolution 2767. The resultant lack of a reliable source of funding has cast serious doubt not only over AUSSOM’s effective functioning but also its continuity.

The estimated budget for AUSSOM from July 2025 to June 2026 is $166.5 million, based on a troop reimbursement rate of $828, according to the UN Secretary-General’s report to the Security Council dated 7 May 2025. However, the financial demands of the mission extend well beyond this figure. AUSSOM needs $92 million in urgent cash requirements for liabilities incurred from January to June 2025. Furthermore, arrears owed to TCCs from 2022 to 2024 total $93.9 million. In contrast, currently committed funding amounts to only $16.7 million, of which $10 million comes from the AU Peace Fund’s Crisis Reserve Facility. The mission’s liabilities continue to mount, with a need for at least $15 million per month.

With Resolution 2719 no longer presenting a viable funding pathway, the AU, T/PCCs, Somalia, and the wider international community now need to work on Plan B for addressing the existential financial crisis facing AUSSOM. The European Union (EU), the single largest direct contributor to AU missions in Somalia—with nearly €2.7 billion provided since 2007— is understandably not keen on maintaining previous levels of support, amid shifting geopolitical priorities. While some EU contributions may still be forthcoming, they are unlikely to bridge the funding gap. Similarly, support from non-traditional donors appears limited, as evidenced by the modest pledges from China, Japan, and South Korea, which amount to no more than $5.6 million.

Against this backdrop, a major area of interest to PSC members during tomorrow’s session is to receive an update on the options being explored and most notably the ongoing effort to organise a pledging conference for AUSSOM. The AU sees this as a potential lifeline for the mission. Although previous attempts to convene the conference in Doha, Qatar, during April and May did not materialise, efforts are underway. While the date is yet to be confirmed, the AU and the Federal Government of Somalia (FGS) are jointly proposing the convening of an AUSSOM Financing Conference. Tomorrow’s session is therefore expected to provide strategic guidance on fast-tracking the convening of the pledging conference, as well as on strategies to secure the necessary financial commitment from international partners.

An update on security and political developments in Somalia is expected to be another key focus of the session. AUSSOM and the Somali National Armed Forces (SNAF) are working to reverse the recent territorial gains made by Al-Shabaab. A major development in this regard is the three-day joint operation code-named ‘Operation Silent Storm,’ launched in June by AUSSOM and SNAF against Al-Shabaab positions in the Lower Shabelle region. The operation, undertaken to recapture the Forward Operating Bases (FOBs) of Sabiid Anole, Aw Degeele and Bashir that were lost to Al Shabaab, registered some success, most notably the recapturing of the key villages of Sabiid and Anole.

On the political front, tensions are escalating as divisions deepen over critical national issues, including the constitutional review process and the electoral model that will be used for the 2026 presidential election. Despite a lack of consensus, President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud appears determined to replace the long-standing clan-based indirect voting system with a one-person, one-vote model for the upcoming election. This has further deepened the rift in the political arena, with various political forces mobilising mounting opposition against the president, with some concerned by the disruption that the shift in the electoral model could cause to the delicate clan-based power-sharing arrangement.

In a development that added another layer of political disquiet, President Sheikh, along with several regional and political leaders, launched a new political party, the Justice and Solidarity Party, ahead of the 2026 election. The party includes leaders from three federal member states—South West, Hirshabelle, and Galmudug, with Puntland and Jubbaland, which remain at odds with the Federal Government, condemning the initiative as lacking constitutionality.

While recent efforts, including the National Consultative Conference (some of whose members were co-opted into the new political party) and the President’s engagement with opposition groups are encouraging, progress on key national issues should be grounded in careful negotiation and inclusive political engagement. As Somalia enters its electoral season, the shifting political landscape is expected to have significant implications for national security. Prolonged and deepening political infighting risks undermining collective and sustained action in bolstering security measures, including the fight against Al-Shabaab. As in the past, Al-Shabaab is likely to exploit such fractures for its own strategic gain.

Against this background, members of the PSC may also reflect on the kind of arrangement that needs to be put in place for stronger collaboration and accountability between the AU, FGS, and donors. As the PSC weighs on the quest for financing of AUSSOM, there is a need for considering a) the options for the immediate future of AUSSOM, b) the plan and options for its exit, c) the alternative security support for Somalia that may be required (including bilateral deployments) both for complementing AUSSOM and ensuring continuity as it draws down and exists and d) the kind of political process, including national reconciliation and negotiation, necessary for the resolution of the conflict involving Al Shabaab.

The expected outcome of the session is a communiqué. The PSC is expected to welcome the successful bilateral negotiations on the draft Memorandum of Understanding (MoU), which outlines the roles, responsibilities, and operational modalities for troop and police contributions to AUSSOM. The PSC may request the AU Commission to expedite the signing of the MoUs as one of the key steps in ending Phase I of the mission (realignment of all AU troops from ATMIS to AUSSOM). The PSC may extend the timeline for repatriation of Burundian troops, while commending them for their irreplaceable contribution to the stabilisation of Somalia and calling for the finalization of deployment of Egyptian troops. Regarding the pledging conference, the PSC may urge the AU Commission, in collaboration with the Government of Somalia and international partners, to work on a solid plan that guarantees success in mobilising the funds required for addressing the dire shortfalls threatening the continuity of AUSSOM. The PSC is also expected to encourage international partners to make the necessary financial commitments. As the AU prepares for the Mid-Year Coordination Meeting later this month, the PSC may also request a continued allocation of an additional amount from the AU Peace Fund. The PSC may also task the AU Commission to develop a plan and options on the immediate future and the steps needed for a smooth drawdown and exit of the mission. Regarding the political situation in Somalia, the PSC is likely to encourage the Government of Somalia to engage in an inclusive political dialogue on key national issues and to ensure that political divisions do not undermine efforts to safeguard and strengthen the stabilisation process in Somalia.