Open Session on the Humanitarian Situation in Africa

Open Session on the Humanitarian Situation in Africa

Date | 30 June 2025

Tomorrow (1 July), the African Union (AU) Peace and Security Council (PSC) is scheduled to convene its 1286th session as an open session to discuss the humanitarian situation in Africa.

The session will commence with opening remarks by Rebecca Otengo, Permanent Representative of Uganda to the AU and Chairperson of the PSC for July, followed by a statement from Bankole Adeoye, Commissioner for Political Affairs, Peace and Security (PAPS). It is also expected that Amma Adomaa Twum-Amoah, Commissioner for Health, Humanitarian Affairs and Social Development (HHS); Churchill Ewumbue-Monono, Permanent Representative of Cameroon and Chairperson of the PRC Sub-Committee on Refugees, returnees, IDPs and Migration; along with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) and the World Food Program (WFP), will brief the Council.

The session is being convened within the framework of the PSC’s annual indicative program of work, with the humanitarian situation in Africa forming part of the thematic standing agenda of the PSC. The last time the PSC convened a session to look at the humanitarian situation in Africa was during its 1239th session on 19 October 2024, where it received a briefing from the ICRC on its activities on the continent.

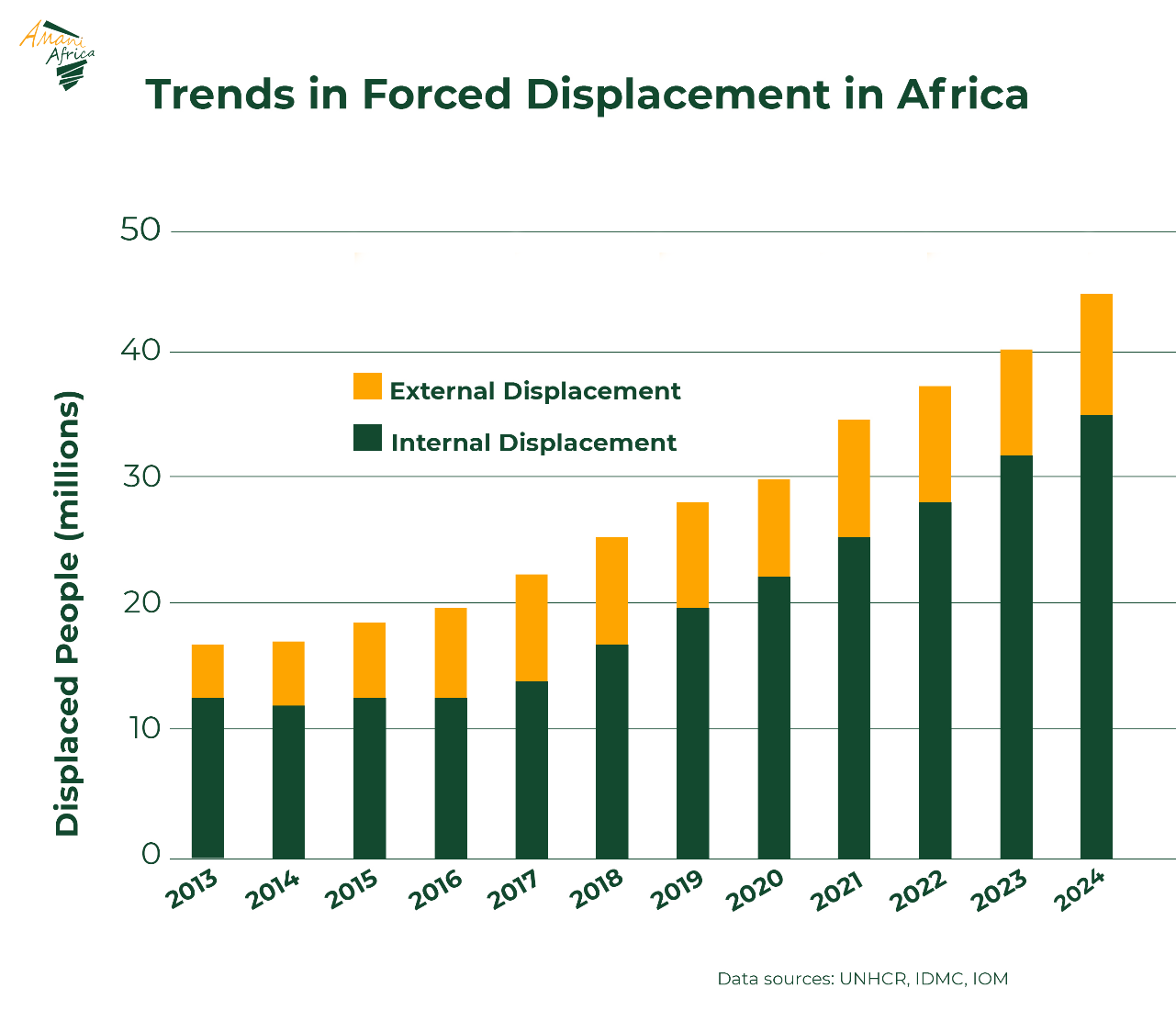

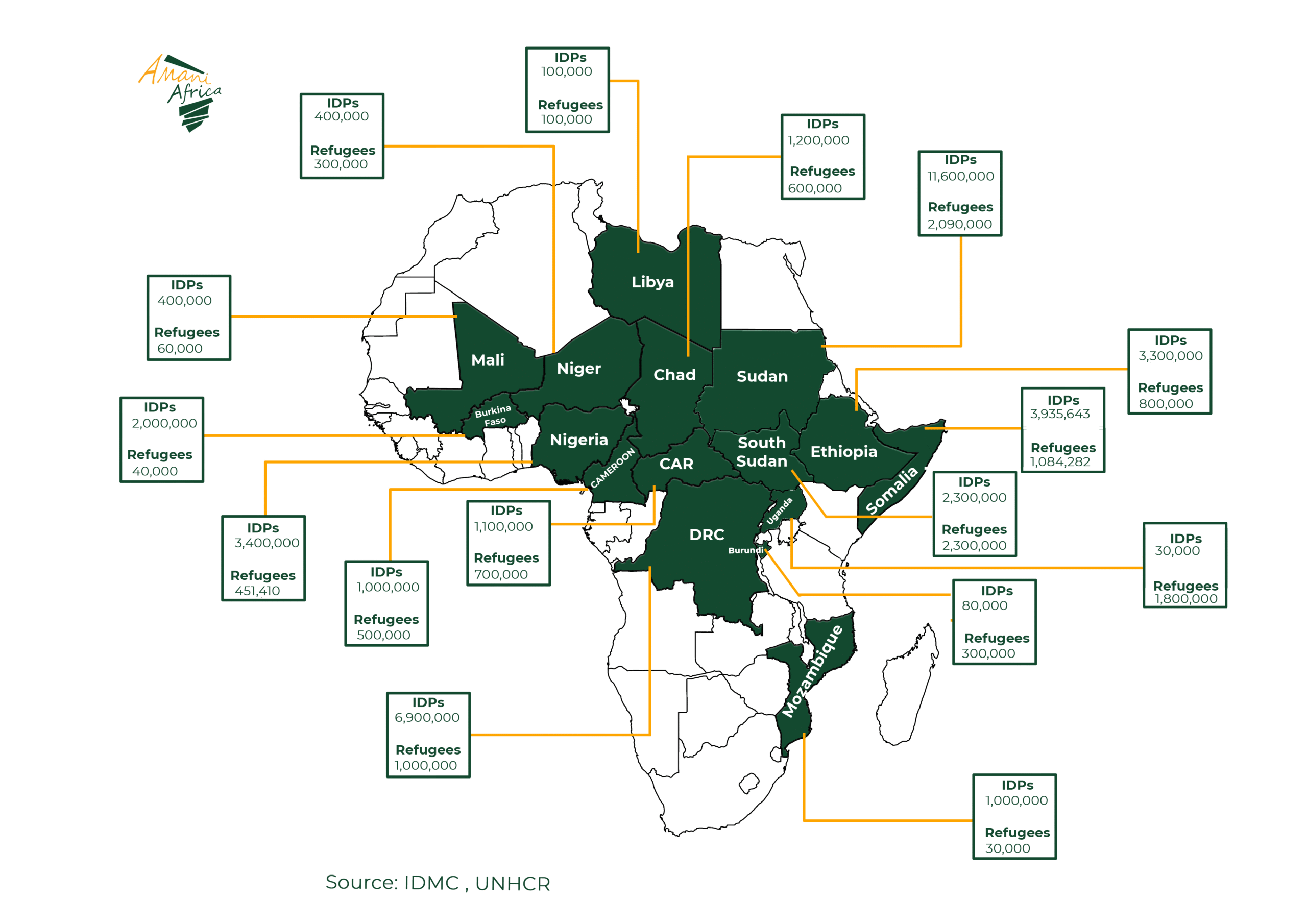

The worsening humanitarian situation in Africa is reaching unprecedented levels due to protracted conflict, climate change, economic fragility, and widening resource gaps, as well as a lack of international attention and mobilisation. Reports from humanitarian actors indicate that the lethal convergence of violent conflict, climate change-induced disasters, and acute funding gaps has resulted in millions across the continent living in conditions of extreme vulnerability and suffering.

Conflict remains a major driver of humanitarian need, with countries such as Sudan, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), and South Sudan facing escalating levels of displacement, food insecurity, and systemic breakdowns in health and basic services, mainly due to conflicts. The latest figures from humanitarian agencies show that in Sudan alone, over 30 million people, more than 63% of the population, are in dire need of humanitarian assistance. The conflict between the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), which erupted in April 2023, has led to the forcible displacement of over 12 million people internally and across borders, representing the largest displacement crisis in the world. Despite the enormity of need, the international humanitarian response has been woefully underfunded. As of April 2025, only 10% of the $4.2 billion appeal to address what has been recognised as the most severe humanitarian emergency in the world had been met, clearly demonstrating the growing disconnect between humanitarian need and global solidarity.

In addition to the scale of the humanitarian need and the growing gap in the resources required for meeting such need, aggravating the dire humanitarian situation is the shrinking humanitarian space, on account of the disregard by conflict parties of humanitarian principles and IHL rules. Thus, in Sudan, the weaponisation of humanitarian aid, especially food, by the warring parties has compounded the suffering of people caught up in the crossfire of violence, with reports of aid blockades and starvation being used as weapons of war, in complete disregard and direct breach of international humanitarian law (IHL) rules. As a result, parts of Sudan, such as Darfur, have been designated as territories classified as having famine conditions.

The DRC presents another grim illustration, particularly of protracted humanitarian distress resulting mainly from conflicts for over two decades. The country now hosts the highest number of internally displaced people ever recorded within its borders, over 7.3 million. Conflict continues to disrupt food systems, healthcare, and shelter, with approximately 27.7 million people expected to face Crisis (IPC Phase 3) or worse food insecurity between January and June 2025. The impacts of climate shocks add to the plight of people in the country; seasonal floods in early 2025 damaged infrastructure in Kinshasa and Equateur, affecting over 60,000 people.

South Sudan’s protracted crisis also demands urgent attention. In 2025, 9.3 million people within the country require humanitarian aid, with an additional 4.3 million South Sudanese living in displacement due to conflict, environmental shocks, and economic collapse. These intersecting drivers of vulnerability highlight the imperative for ensuring the implementation of the peace process and completing the transitional period in order to create space for a more focused policy action involving both preparedness and response to climatic distress.

In addition to these, the Norwegian Refugee Council’s (NRC) 2025 report indicates that 8 of the world’s 10 most neglected humanitarian crises are located in Africa, including those in Cameroon, Ethiopia, Mozambique, Burkina Faso, Mali, Uganda, and Somalia.

However, despite the scale of the humanitarian crises represented by the staggering figures, the international response has fallen drastically short, and Africa’s humanitarian financing landscape remains starkly inadequate. According to the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), over half of the global $25 billion appeal for humanitarian assistance went unmet in 2024. Within Africa, funding gaps were particularly severe. Burkina Faso, for instance, received only 27% of its appeal.

In light of this chronic underfunding, tomorrow’s session is expected to focus on financing humanitarian responses. It would follow up on the decision of the Council’s 1239th session where Council members acknowledged chronic financing shortfalls and requested the AU Commission to undertake a comprehensive study, identifying financial shortfalls and developing practical proposals for sustainable humanitarian resource mobilisation. One of the issues for members of the PSC is to identify and institutionalise alternative and innovative financing mechanisms, including, as previously proposed, through a more robust engagement with the African private sector. This can draw on some of the promising experiences registered in this regard in 2024 with the Peace Fund’s outreach to private sector actors like Safaricom and Afreximbank, which mobilised resources for funding humanitarian infrastructure in regions emerging from conflict. However, for such sources of finance to contribute meaningfully, there is a need for the AU to develop a strategy for partnership with and mobilisation of resources from the private sector and other sources such as philanthropies. It is also necessary that the AU institutes financial rules and processes tailored to funds resourced from the private sector, including for embedding agility in the receipt and use of funds in response to pressing needs. The AU may also need to consider how to leverage the Africa Risk Capacity (ARC).

Strengthening public-private partnerships could complement state-level contributions and offer greater sustainability in meeting humanitarian obligations. The OCHA–UNDP Connecting Business Initiative (CBi), which strategically engages the private sector before, during, and after emergencies, provides a useful model in this regard, having mobilised over $132 million since its establishment in 2016 and reached more than 55 million people through crisis response.

The PSC may also wish to revisit its decision from its 1176th session held on 29 September 2023, for the AUC to lead an all-Africa mega pledge covering areas such as food security, displacement, climate-induced disasters, and post-conflict reconstruction, and revive momentum for increased continental resource mobilisation. Yet, for any such pledging to be effective, there is a need to put in place a mechanism to track pledged commitments and ensure implementation. Such pledge monitoring mechanisms could enhance transparency and accountability of humanitarian pledges, including those made at previous high-level events for Sudan and the Horn of Africa. The Humanitarian Coordination Forum (HCF), led by the HHS Directorate in collaboration with OCHA, may play a role in this regard by monitoring donor commitments and following implementation.

The other challenge that has particularly become acute during the past few years is the lack of international attention to situations on the continent. Crisis situations, such as Sudan, did not receive even a fraction of the attention given to crises in Europe and the Middle East. A further factor is the shift of resources away from aid and towards defense spending. It is feared that the restructuring of the UN, expected to be implemented for cutting funds under the UN80 initiative, will further compound the situation, as it leads to major layoffs on the part of UN agencies critical to humanitarian action.

The weak and dwindling international attention to the protracted and overlapping crisis is further compounded by a chronic deficit in political mobilisation and coordinated diplomacy on the continent. As humanitarian needs reach record levels and global solidarity frays, the urgency for Africa to mobilise its political and institutional resources has never been greater. In this context, the AU’s role in humanitarian diplomacy remains central. Drawing on its legitimacy and political convening power, the Union is well-positioned to facilitate humanitarian access, and promote compliance with international humanitarian law (IHL) and mobilise attention and support for humanitarian emergencies.

Another issue expected to surface during tomorrow’s session is the follow-up on the progress of the operationalisation of the African Humanitarian Agency (AfHA), which is set to be operational this year. Established by the decision of the 2022 Malabo Extraordinary Humanitarian Summit and consistently reaffirmed, AfHA is expected to go operational, headquartered in Uganda.

The expected outcome of tomorrow’s session is a communiqué. The PSC may call for the fast-tracked operationalisation and financing of the African Humanitarian Agency (AfHA), as well as increased contributions to the Special Emergency Assistance Fund (SEAF) and the Africa Risk Capacity (ARC). The PSC may call on member states to uphold their responsibilities by ensuring respect for IHL rules and ensuring unhindered humanitarian access. It may also underscore the responsibility of conflict parties not only to adhere to IHL and facilitate humanitarian access but also to cooperate with initiatives for peace, including by following through on commitments made in peace agreements. The Council may call for enhancing coordination between the AU’s Continental Early Warning System (CEWS), Africa Multi-Hazard Early Warning and Early Action System (AMHEWAS), launched in 2022, the Space for Early Warning in Africa (SEWA) project, launched in June 2025, national platforms, and predictive tools such as the World Food Programme’s HungerMap LIVE. Embedding these systems within AU and Regional Economic Community (REC) protocols, supported by standard operating procedures and data-sharing frameworks, can enable rapid detection of emerging crises, timely resource mobilisation, and community-centered responses. Reiterating its call for finding alternative and innovative sources of financing humanitarian action in Africa, the PSC may request the AU Commission to develop a strategy for partnership with the private sector and philanthropies and institutionalising the sourcing of funds for addressing the humanitarian funding shortfall in Africa.

Provisional Programme of Work of the Peace and Security Council for July 2025

Provisional Programme of Work of the Peace and Security Council for July 2025

Date | July 2025

The Republic of Uganda is set to chair the African Union (AU) Peace and Security Council (PSC) in July 2025. Last April, Uganda also served as the stand-in Chair.

The Provisional Programme of Work (PPoW) for the month envisages five substantive sessions. Three of these will be thematic, while the remaining two will focus on country situations. The sessions will be convened at all three levels of the Council: three at the Ambassadorial level, one at the Ministerial level, and another one tentatively scheduled to be held at the Heads of State and Government level. One of the thematic sessions—the humanitarian situation in Africa—is expected to be held as an open session. The remaining sessions will be conducted in a closed format.

In addition to the substantive sessions, meetings of the Military Staff Committee and the Committee of Experts are scheduled. The PSC is also expected to travel to Midrand, South Africa, for the annual consultative meeting with the Pan-African Parliament (PAP).

The first session of the month, scheduled for 1 July, will focus on the humanitarian situation in Africa. The session will be held in an open format, allowing for the involvement of all AU member states, UN entities, and civil society organisations engaged in humanitarian action. The last time the PSC dedicated a session to this theme was in October of last year, during its 1239th meeting, when the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) briefed the Council on the humanitarian situation in Africa. Although no outcome document was publicly released from that session, the PSC made several key decisions, including undertaking a comprehensive study, identifying financial shortfalls, and proposing concrete and practical measures to address the funding gaps for meeting Africa’s humanitarian needs. Building on these earlier commitments, discussions are expected to delve into the consequences of shrinking humanitarian aid, its impact on humanitarian agencies and frontline workers, and the escalating crises in refugee and IDP camps. The session is also expected to explore mechanisms for securing sustainable and predictable financing to support humanitarian responses across the continent and follow up on the operationalisation of the African Humanitarian Agency.

On 3 July, the PSC will hold its second ministerial-level session to receive updates on the situation in Somalia and the operations of the AU Support and Stabilisation Mission in Somalia (AUSSOM). The meeting follows a significant setback at the UN Security Council on 12 May, when the Council failed to authorise the activation of Resolution 2719 as a funding framework for AUSSOM. The AU had considered the resolution the most viable option for securing sustainable, predictable, and adequate funding for the mission. The session is also expected to follow up on the outcome of the Kampala summit of Troop Contributing Countries (TCCs). The session is also expected to feature an update on recent progress regarding the operationalisation of the mission, particularly the conclusion of bilateral Memorandum of Understanding (MOUs) between the AU Peace Support Operations Division and key Troop- and Police-Contributing Countries (T/PCCs). Negotiations, held from June 10 to 19, 2025, culminated in an agreement on the content of the draft MOUs, which outline the roles, responsibilities, and operational modalities for the contribution of troops and police personnel to the mission, according to the AU’s press release. The MOUs are expected to be signed by the AU and each of the participating T/PCCs after the final draft receives clearance from the Office of the Legal Counsel of the AU. In this context, the session is also expected to examine the evolving role of both the AU and T/PCCs within the broader landscape of mission financing and explore strategies to address the current funding challenges.

The PSC will convene its third substantive session on 4 July to consider the bi-annual Report of the AU Commission on Elections in Africa, covering the period from January to June 2025. The Chairperson’s mid-year report on elections is in line with the PSC’s decision at its 424th session in March 2014 to receive regular briefings on national elections on the continent. The most recent such briefing took place during the Council’s 1255th session on 24 January 2025, which reviewed elections held between July and December 2024. The upcoming session will provide an overview of elections conducted during the first half of 2025, along with a snapshot of those scheduled for the second half of the year.

On 22 July, the PSC will convene to discuss the theme ‘Rehabilitation and Reintegration of Children Formerly Associated with Armed Conflicts.’ The focus on this theme is within the framework of the assumption by Rebecca Amuge Otengo, Uganda’s Permanent Representative to the AU and Chair of the PSC for July, of the role of Co-Chair of the Africa Platform on Children Affected by Armed Conflicts (AP-CAAC) in May. The issue of Children Affected by Armed Conflict (CAAC) has been a standing agenda item of the PSC since 2014 and regularly features in its deliberations. Most recently, in February 2025, during its 1262nd session, the PSC addressed ‘The Fight against the Use of Child Soldiers in Africa.’ In that session, the Council called on the AP-CAAC and other stakeholders to maintain engagement with affected regions and communities to ensure the successful rehabilitation and reintegration of children formerly associated with armed groups. In this regard, the session is expected to include reflections from representatives of some member states on their experiences in the rehabilitation and reintegration of children in post-conflict situations. Their testimony will serve as a powerful reminder of both the vulnerabilities and potential of children affected by armed conflict. The session will also provide a platform to explore concrete steps for operationalising existing commitments, as well as to follow up on the implementation of previous decisions and initiatives. This includes the reiteration of the long-standing request for the Chairperson of the African Union Commission to appoint a Special Envoy for Children Affected by Armed Conflict (CAAC) in Africa.

The final substantive session of the month, scheduled for 24 July at the level of Heads of State and Government (HoSG), will focus on the situation in Libya. This marks the first time since the PSC’s 294th session in September 2011 that Libya will be discussed at the level of Heads of State and Government. The recent uptick in both the frequency and level of the Council’s engagement with the Libya file marks a shift, with this being the second meeting in just two months. The session follows the 23 May convening prompted by clashes between rival militias in Tripoli on 12 May, providing an opportunity to receive updates since its last meeting. Another significant development expected to be discussed is the reconvening on 20 June of the Berlin Process International Follow-up Committee on Libya (IFC-L), after a four-year hiatus, with the AU among the participants. The UN Support Mission in Libya has also been working on a ‘time-bound and politically pragmatic roadmap’ to end the transitional process, which the PSC is likely to receive an update on. Libya remains divided between the internationally recognised Government of National Unity in Tripoli and the rival Government of National Stability in Benghazi, amid a fragile 2020 ceasefire agreement and fluid security conditions, as evidenced by the 12 May clash. Initial progress towards a political solution to the Libyan crisis has stalled, and holding a national election remains elusive after its indefinite postponement in December 2021. Despite efforts, including the signing of the Libyan Reconciliation Charter in Addis Ababa on February 14, progress toward national reconciliation remains challenging.

Aside from the substantive sessions, PSC’s Military Staff Committee (MSC) is scheduled to convene virtually on 2 July to discuss the implementation of PSC Communiqué 1275 of 23 April 2025 on the Imperative of a Combined Maritime Task Force in Addressing Piracy in the Gulf of Guinea (for details on the outcomes of PSC’s 1275th session, see our analysis here and here). On 21 July, the Committee of Experts (CoE) is also expected to meet to prepare for the PSC’s summit-level session on Libya. The CoE is likely to work on the draft communiqué to be considered during the summit. From 25 to 26 July, the CoE will further convene for a ‘Capacity building on the reactivation of the PCRD subcommittee,’ as well as for ‘Consideration of the PAPS Input Paper on the Reform of the AU Liaison Offices.’ Other activities include the 4th Policy Session of the AU Inter-Regional Knowledge Exchange (I-RECKE) on 12 July; the PSC–PAP Annual Consultative Meeting on 17-18 July in Midrand, South Africa; and the 13th High-Level Dialogue on Democracy, Governance, Human Rights, and Peace and Security, to be held from 29 to 30 July in Accra, Ghana.

Of particular significance, a possible ministerial meeting of the PSC Ad Hoc Presidential Committee on Sudan is envisaged to take place on the margins of the 7th Mid-Year Coordination Meeting in Malabo, Equatorial Guinea, scheduled for 10–13 July. If held, it would be the first meeting of the Committee since PSC’s decision to form the Ad Hoc Committee in June 2024.

Will the FFD4 in Seville break from the past or perpetuate a cycle of neocolonial extraction?

Will the FFD4 in Seville break from the past or perpetuate a cycle of neocolonial extraction?

Date | 29 June 2025

Dalaya Ashenafi Esayiyas[1]

|

As global elites gather in Spain for the Fourth International Conference on Financing for Development (FFD4) starting from tomorrow 30 June, their exists no indication that this forum will not once again peddle the same old myths: that more loans, ‘sustainable’ debt frameworks, and technocratic tinkering can ‘fix’ Africa’s financial crisis, characterised by cyclical heavy indebtedness. But after decades of empty promises, the trend is clear: the current system is not broken, it is working exactly as designed. From Zambia’s vulture fund lawsuits to Ghana’s IMF-mandated hunger riots, the models of Africa’s access to ‘development finance’ remain a neocolonial project of extraction, enforced through spreadsheets and austerity. If FFD4 refuses to confront this reality, it will be just another stage for the financial empire’s theatre of hypocrisy. |

The Illusion of Reform, Restructuring and ‘Development Finance’

On 20 June 2025, a distinguished commission of global experts convened by the Pontifical Academy of Social Sciences and Columbia University’s Initiative for Policy Dialogue issued a damning indictment of the global financial system. Their report’s bold recommendations, designed to unshackle developing nations from debt traps and fast-track equitable development, would be ideal for a system that had lost its way and sought reform through dialogue. Another similarly groundbreaking report of the World Inequality Database, released on 9 June 2025, proposed structural reforms of the international monetary and exchange system, focusing, among others, on a centralised system of credits/debts with a common borrowing rate.

But the global financial system operates exactly as intended: as a rigged game that extracts wealth from the Global South while offering false solutions. The two reports’ urgent call for systemic change only underscores how profoundly the current architecture serves creditors, based exclusively on a profit logic, over people, inducing recurrent ‘crises’ and turning ‘crisis management’ into permanent control.

In 2023, Zambia spent more on debt payments to creditors, including British bankers, than on healthcare for its 20 million citizens. Take, as another example, the pressure exerted on Zambia and Ghana to default on loans from the African Export-Import Bank (Afreximbank) and the Trade and Development Bank (TDB) by insisting that these banks should not enjoy preferred creditor status of multilateral financial institutions and undermining the banks’ credit ratings and increase their borrowing costs with dire consequences for African states.

These are not anomalies; they show the neocolonial financial order working exactly as designed. For all the talk of ‘development finance’ and ‘debt relief,’ the brutal truth remains: Africa is caught in a debt trap engineered by the same powers that once colonised it through armies and now do so through spreadsheets.

African nations borrow not for development but to service old debts, stabilise currencies looted by capital flight, and pay for imports made necessary by trade imbalances enforced by the inequitable global financial and trading system. In 2023, Ghana took $3B IMF bailout to stabilise its economy. The reality was that the bailout came with painful cuts. VAT hikes on electricity, fuel subsidy cuts (sparking 54% inflation), and deepening trade Imbalance. The outcome has been citizens paying exponentially more for basic goods while gold revenues (controlled by Newmont Mining) bypass state coffers.

As the global financial system operates like a rigged casino benefiting the powerful, the odds are stacked against the Global South. Despite decades of promises, debt ‘relief’ initiatives, and technocratic tinkering, Africa is never relieved. It remains trapped in a neocolonial cycle of extraction, austerity, and dependency. The latest proposals, debt sustainability analyses (DSAs), Special Drawing Rights (SDR) recycling, and local currency lending, are presented as solutions, but they are little more than band-aids on a bullet wound.

This is not a crisis of bad policy; it is the logical outcome of a financial empire designed to enable those who designed it to develop, while keeping parts of the world like Africa at the bottom of the development pyramid. From the IMF’s structural adjustment programs (SAPs) of the 1980s to today’s ‘debt transparency’ frameworks, the game remains the same: extract wealth, enforce obedience, and maintain control while offering ‘solutions’ for making the symptom of the illness tolerable.

The IMF’s Austerity Trap

Debt Sustainability Assessments (DSAs) often tend to be little connected to the economic realities. Like an outdated map, they often fail to account for the actual terrain of a country’s fiscal challenges and growth potential. The IMF claims DSAs will prevent ‘unsustainable’ borrowing, but who defines what is ‘sustainable’? The same institution that forced Ghana to slash fuel subsidies in 2023, sparking riots?

The IMF’s austerity conditionality constitutes structural violence through fiscal policy, undermining the pledges made under the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). By mandating wage cuts, healthcare privatisation, and labour deregulation in debtor nations, these programs institutionalise poverty, divert the little resources of poor countries away from meeting the survival needs of citizens to servicing debt.

This is directly associated with the outdated power dispensation that structured the design and operation of the IMF and the World Bank. First, we have voting shares at the World Bank that still reflect 1945 power dynamics, whereby nearly 95% of African states hold less than 5% while the countries that designed the system, like the US, hold more than three times more. Second, local currency lending is a distraction when the system is hardwired for dollar dependency, and Africa loses more to illicit financial flows, capital flight ($88.6B/year, UNECA) than it receives in aid. Third, private creditors who hold a significant amount of the south’s debt and vulture funds operate to entrench extractivism. After defaulting on its debt, Zambia was sued by British Virgin Islands-based vulture funds demanding 300% returns. The IMF’s ‘restructuring’ deal protected bondholders while Zambians faced fuel queues and medicine shortages.

Despite its years of demand for reform, the reality is that Africa, left with no other choice, continues to engage. Highlighting its unwillingness to relinquish its dominance willingly, the financial empire persists to deflect responsibility and block necessary changes. If Seville is to mark a break from the continuation of the status quo, it must allow the replacement of the system, as the WID report and many others argued, by ‘a more inclusive and mutually beneficial trade and monetary system.’

The Missing Alternatives

There are development advancing alternatives ranging from the cancellation of Illegitimate debts to pegged exchange rates closer to purchasing power parities and/or a common currency and a centralised system of credits/debts with a common borrowing rate.

Most African debt is odious, often borrowed on extortionist terms, including via IMF conditionalities. African countries can demand an independent audit (like Ecuador did in 2007) and repudiate predatory loans.

Also missing is ‘a credible, comprehensive mechanism for sovereign debt relief,’ which is also called for by the Vatican-Columbia University sponsored Commission.

Additionally, there will be no meaningful benefit to be gained from making concessions on the African Group’s position for the FfD4 calling for the establishment of a time-bound global sovereign debt authority, echoing the Report of the Namibia-Amani Africa High-Level Panel of Experts on Africa and the Reform of the Multilateral System.

Africa also needs to be serious about continental financial and monetary integration to ensure financial sovereignty. It is time to think about regional currencies and implement the pan-African payment and settlement platform. Capital controls need to be implemented to fight illicit financial flows.

Unless Seville marks a complete break from the past and ushers in firm commitment on the overhaling of the global financial architecture, there is little prospect that the tinkering on the margins and committing to future reform of the international financial institutions would be enough to ending the cycle of heavy indebtedness and extortionist terms of access to development finance and to meet the development needs, including the realisation of the SDGs.

[1] Dalaya Ashenafi is an Ethiopian political economist and strategist whose work critically engages with structural inequality, state power, and emancipatory development alternatives. She can be reached at [email protected]

The content of this article does not represent the views of Amani Africa and reflect only the personal views of the authors who contribute to ‘Ideas Indaba’

AFRICA AT A TURNING POINT: NAVIGATING PERIL AND SEIZING OPPORTUNITY IN A CHANGING GLOBAL ORDER

AFRICA AT A TURNING POINT: NAVIGATING PERIL AND SEIZING OPPORTUNITY IN A CHANGING GLOBAL ORDER

Date | 26 June 2025

Said Djinnit*, Ibrahim Assane Mayaki** and El-Ghassim Wane***

In July 1990, nearly thirty-five years ago, Salim Ahmed Salim, then Secretary-General of the Organization of African Unity (OAU), presented a landmark report to the 52nd Ordinary Session of the OAU Council of Ministers entitled ‘The Fundamental Changes Taking Place in the World and Their Consequences for Africa—Proposals for an African Position.’

The idea for this seminal document was born in the early days of Salim’s tenure at the organisation’s helm. Drawing on his extensive diplomatic experience, Salim was struck by the weakening commitment of member states to the OAU’s founding ideals. With the liberation struggle largely over and apartheid beginning to collapse, the OAU—long defined by its role in ending foreign domination and minority rule—now found itself in search of a new raison d’être.

And yet, the challenges had not disappeared—they had simply evolved. While some conflicts were coming to an end, others persisted or erupted. Economic development and continental integration remained more aspirational than real. The human rights situation was no less troubling. Democracy, though gaining ground in parts of the continent, was still fragile, its future uncertain.

Africa urgently needed to reposition itself as the world underwent seismic shifts—the Cold War’s end, democratisation in Eastern Europe, and accelerating regional integration in Europe and the Americas. These changes demanded adaptation and offered opportunities Africa could not afford to miss, or risk being sidelined in the emerging global order.

Salim did more than offer a candid diagnosis of the continent’s predicament—he also advanced concrete proposals, which were endorsed by the OAU Summit in the July 1990 Declaration on the Political and Socio-Economic Situation in Africa and the Fundamental Changes Taking Place in the World. The Declaration became a catalyst for a broad spectrum of decisions and initiatives across the organisation’s areas of work. Many of the African Union’s (AU) subsequent achievements can be traced directly to the foundations laid by these landmark documents.

If action was urgent in 1990 post-Cold War optimism, it is even more so today—driven not by hope, but by uncertainty

There is a striking parallel between that period and the one we are living through today: the magnitude of the upheavals. The multilateral system conceived in the aftermath of the Second World War is arguably undergoing the most profound crisis in its history. National self-interest is resurgent, reflected in the rise of anti-migrant sentiment and a sharp decline in development assistance. International law—never fully insulated from the realities of power politics—continues to suffer serious violations.

This new global context is fraught with dangers for Africa. As the most vulnerable continent on the international stage, Africa is bearing the full brunt of the reduction in official development assistance. Geopolitical and other tensions are fueling renewed quests for influence and a growing internationalisation of the crises that afflict the continent. The erosion of the multilateral system risks further marginalising African countries, exposing them to bilateral power dynamics in which their structural vulnerabilities leave them at a severe disadvantage.

Nonetheless, this crisis may also present an opportunity. As damaging as the decline in international aid may be in the short and medium term, it could serve as a salutary shock – a stark reminder of the urgent need for the continent to reduce its dependency. The ongoing reconfiguration of the global order can—and must—be harnessed as an opportunity, and only by capitalising on its unity will Africa be able to contribute meaningfully to shaping the architecture of the emerging world order.

If the imperative to act was already pressing in 1990—an era of post-Cold War optimism and renewed multilateralism—it is even more urgent today, not driven by hope but by the necessity of navigating a period of profound instability and uncertainty.

The good news is that Africa now possesses assets it lacked in the early 1990s. Then, the priority was to build the political, normative, and institutional foundations for collective action. That work is largely done. Today, across all strategic domains—peace and security, (here, here, here, here and here), governance and democracy (here, here, here and here), human rights (here, here, here, here, here, here and here) and development (here, here and here)—Africa has robust frameworks. Agenda 2063 unifies them within a shared long-term vision, reinforced by dedicated institutions.

Africa’s urgency today lies not in new commitments, but in delivering on those already made

Yet this impressive normative and institutional arsenal still struggles to deliver the expected results. Africa’s economic transformation remains a distant prospect. Exports are still dominated by raw materials, and intra-African trade hovers around 15%. Nearly 67% of the world’s extreme poor live in sub-Saharan Africa. Infrastructure gaps persist, visa restrictions hinder mobility, democratic processes are under strain, and armed conflicts and displacement affect every region.

This gap between Africa’s normative and political ambitions and the realities on the ground is, above all, the result of limited implementation capacity. Africa doesn’t lack tools. What is needed now is a paradigm shift: placing the execution of existing commitments at the core of the continental agenda.

In this light, Salim Ahmed Salim’s 1990 intuition remains deeply relevant. The new AU Commission stands at a pivotal moment, with a unique opportunity to lead through a bold, forward-looking initiative: producing a foundational report—echoing the spirit of the 1990 landmark, but with greater ambition and broader mobilisation to match today’s scale and urgency.

Such a report should provide an unflinching assessment of the continent’s current state and put forward responses centred on one core priority: the effective implementation of commitments already made. It should also reaffirm a fundamental truth: Without unity, Africa will remain easy prey in a world that has never spared the weak—and does so even less today.

Once completed, the new report should be discussed at an extraordinary AU summit in Addis Ababa, bringing together all member states at the highest level. Of course, no report alone can resolve the continent’s many challenges. In the end, it is just a document. But if well crafted—if it captures imaginations, is grounded in truth, and followed by real commitments—it can serve as a powerful driver of change.

In this effort toward renewal, the AU must occupy a central place. As the continent’s legitimate institutional framework for unity, the AU is best positioned to articulate Africa’s collective voice and ambitions. In this regard, a troubling trend must be reversed: summits held with external partners often attract more heads of state and government than the AU’s own meetings.

In May 1963, during the debate in Addis Ababa between those favouring a gradual approach to African unity and those advocating immediate political integration, Kwame Nkrumah may have erred by being ahead of his time. Yet history has since validated the essence of his vision: the limitations of the approach adopted at the founding of the OAU are now evident, and the consequences of deferred integration and unity continue to adversely shape the continent’s trajectory. It is now incumbent upon Africa’s current leaders to do justice to that early intuition, however belatedly.

*Ambassador Said Djinnit served as Chief of Staff to Salim Ahmed Salim (1989–1999), later becoming OAU Assistant Secretary-General for Political Affairs and AU Commissioner for Peace and Security. He was also UN Special Representative in West Africa and later Special Envoy for the Great Lakes (2008–2019).

**Dr. Ibrahim Assane Mayaki of Niger was CEO of AUDA-NEPAD (2009–2022), and previously served as Prime Minister and Minister of Foreign Affairs (1997–2000).

***El-Ghassim Wane held senior AU roles, including Director of Peace and Security and Chief of Staff. He also served as UN Assistant Secretary-General for Peacekeeping and Special Representative in Mali and head of MINUSMA.

Why the AU’s 2025 Theme of the Year Matters for the Reform of the Multilateral System

Why the AU’s 2025 Theme of the Year Matters for the Reform of the Multilateral System

Date | 26 June 2025

INTRODUCTION

The 2025 African Union (AU) theme of the year is ‘Justice for Africans and peoples of African descent through reparations.’ This special research report introduces the background to the theme of the year and examines how the focus on remedying the way the international system is shaped by these historical injustices can help narrow the gap between the commitments of international human rights and the Sustainable Development Goals on the one hand and how the international financial and trading system operate in practice vis-à-vis Africa and parts of the world affected by slavery and colonialism.

L’Afrique à la croisée des chemins: naviguer entre périls et opportunités dans un ordre mondial en pleine mutation

L’Afrique à la croisée des chemins: naviguer entre périls et opportunités dans un ordre mondial en pleine mutation

Date | 26 Juin 2025

Said Djinnit*, Ibrahim Assane Mayaki** et El-Ghassim Wane***

Il y a un peu moins de trente-cinq ans, en juillet 1990 plus précisément, Salim Ahmed Salim, alors Secrétaire général de l’Organisation de l’unité africaine (OUA), présentait à la 52e session ordinaire du Conseil des ministres de l’OUA un rapport devenu historique: « Les changements fondamentaux qui se produisent dans le monde et leurs conséquences pour l’Afrique – Propositions pour une position africaine ».

L’idée de ce document remontait pratiquement à l’arrivée de Salim à la tête de l’organisation. Fort d’une riche expérience diplomatique, il était frappé par le relâchement de l’engagement des États membres envers les idéaux fondateurs de l’OUA. Avec le quasi-parachèvement de la libération du continent du joug colonial et le début de l’effondrement du régime de l’apartheid, l’organisation – dont l’action avait jusqu’alors essentiellement porté sur la lutte contre la domination étrangère et la discrimination raciale – semblait être en quête d’une nouvelle vocation.

Et pourtant, les défis ne manquaient pas – ils avaient simplement changé de nature. Si certains conflits touchaient à leur fin, d’autres persistaient ou éclataient. Le développement économique et l’intégration continentale relevaient davantage du registre des vœux pieux que de celui de la réalité vécue. La situation des droits de l’homme était tout aussi préoccupante. L’idéal démocratique connaissait certes une nouvelle jouvence, mais la trajectoire demeurait incertaine et fragile.

La nécessité pour l’Afrique de se repositionner était d’autant plus impérative que le monde traversait des bouleversements majeurs: fin de la Guerre froide, vent de démocratisation en Europe de l’Est et accélération des dynamiques d’intégration en Europe et aux Amériques. Ces mutations imposaient une adaptation en même temps qu’elles offraient de nouvelles opportunités que le continent se devait de saisir, sous peine d’être relégué en marge du nouvel ordre mondial alors en gestation.

Salim ne se contenta pas de dresser un état des lieux, sans concession: il formula également des propositions concrètes qui furent entérinées par la Déclaration sur la situation politique et socioéconomique en Afrique et les changements fondamentaux qui se produisent actuellement dans le monde, adoptée par le sommet tenu en juillet 1990. Cette Déclaration devait inspirer une série de décisions et d’initiatives couvrant l’ensemble des domaines d’intervention de l’organisation. Bon nombre des progrès accomplis par la suite par l’Union africaine (UA) se sont inscrits dans le prolongement direct de ces documents fondateurs.

Si la nécessité d’agir était déjà pressante en 1990, dans le climat d’optimisme de l’après-Guerre froide, elle l’est encore davantage aujourd’hui — non plus portée par l’espoir, mais imposée par l’incertitude.

Il existe un parallèle saisissant entre cette période et celle que nous traversons aujourd’hui: celui-ci réside dans l’ampleur des bouleversements en cours. Le système multilatéral tel qu’il a été conçu au lendemain de la Seconde Guerre mondiale traverse sans doute la crise la plus profonde de son histoire. Les égoïsmes nationaux connaissent un regain manifeste, illustré par la montée des sentiments anti-migrants et la réduction marquée de l’aide au développement. Quant au droit international – jamais totalement affranchi de la réalité des rapports de forces, il continue de faire l’objet de violations graves.

Cette nouvelle conjoncture mondiale est lourde de périls pour l’Afrique. Continent le plus vulnérable sur la scène internationale, l’Afrique subit de plein fouet la réduction de l’aide publique au développement. Les tensions géopolitiques et autres se traduisent par l’intensification des luttes d’influence sur le continent et l’internationalisation croissante des crises qui l’affligent. L’affaiblissement du système multilatéral risque de marginaliser encore davantage les pays africains, en les livrant à des rapports de force bilatéraux où leurs fragilités structurelles les désavantagent fortement.

Pourtant, cette crise peut aussi être une opportunité. Pour dévastatrice qu’elle soit sur les court et moyen termes, la contraction de l’aide internationale pourrait être un choc salutaire, en ce qu’elle constitue un rappel brutal de l’urgence que revêt la réduction de la dépendance du continent envers ses partenaires internationaux. La recomposition en cours du système international constitue un levier que l’Afrique pourrait – et devrait – mettre à profit pour peser sur l’architecture mondiale en gestation, et ce en faisant le pari résolu de l’unité.

Si l’impératif d’agir était déjà fort en 1990 – époque marquée par l’optimisme post-Guerre froide et l’éveil d’un nouvel esprit de coopération, il est aujourd’hui encore plus pressant, car dicté non plus par l’espoir, mais par la nécessité de faire face à une période d’instabilité et d’incertitudes profondes.

La bonne nouvelle est que l’Afrique dispose aujourd’hui d’atouts qu’elle n’avait pas au début des années 1990. À l’époque, il fallait bâtir les instruments politiques, normatifs et institutionnels dont le continent avait besoin pour agir collectivement. Ce travail a depuis été largement accompli. Il n’existe aujourd’hui aucun domaine stratégique pour l’Afrique – paix et sécurité (ici, ici, ici, ici et ici), gouvernance et démocratie (ici, ici, ici et ici), droits humains (ici, ici, ici, ici, ici, ici et ici) et développement (ici, ici et ici) qui ne soit couvert par un cadre continental pertinent. L’Agenda 2063 donne une cohérence d’ensemble à tous ces instruments, les inscrivant dans une vision stratégique partagée et adossée à des institutions dédiées spécifiquement à leur suivi et mise en œuvre.

L’urgence pour l’Afrique aujourd’hui ne réside pas dans l’adoption de nouveaux instruments, mais dans la mise en œuvre de ceux déjà en place.

Mais cet impressionnant arsenal normatif et institutionnel peine encore à produire les résultats attendus. La transformation économique du continent est encore à réaliser, avec des exportations toujours dominées par les matières premières. Le commerce intra-africain stagne à des niveaux anémiques – autour de 15 %. La partie subsaharienne du continent abrite près de 67% des personnes vivant dans l’extrême pauvreté dans le monde. Les besoins en infrastructures demeurent massifs, les politiques restrictives en matière de visa entravent la libre circulation des personnes, les processus démocratiques sont sous tension, conflits armés et déplacements forcés de populations affectent pratiquement toutes les régions du continent.

Ce fossé entre l’ambition normative et politique, d’une part, et la réalité du terrain, de l’autre, s’explique avant tout par un déficit de capacité de mise en œuvre. L’Afrique n’a pas besoin de nouveaux outils. Ce dont elle a besoin, c’est d’un basculement stratégique: faire de l’exécution des engagements pris la priorité absolue.

À cette aune, l’intuition de Salim Ahmed Salim en 1990 demeure plus pertinente que jamais. La nouvelle Commission de l’UA se trouve aujourd’hui à un moment charnière, qui lui donne une opportunité unique de marquer son mandat par une initiative audacieuse et structurante. Il s’agit pour elle de prendre l’initiative d’un rapport fondateur, dans la veine de celui de 1990, mais avec une ambition plus grande et une mobilisation plus forte pour être à la hauteur des urgences et enjeux de l’heure.

Un tel document devra dresser un diagnostic sans complaisance de l’état actuel du continent et proposer des réponses centrées sur la mise en œuvre effective des engagements déjà pris. Il devra aussi rappeler cette vérité fondamentale: sans unité, l’Afrique continuera à s’offrir en proie facile dans un monde qui n’a jamais eu pitié des faibles – et en a encore moins aujourd’hui.

Une fois finalisé, le rapport devrait être soumis à un sommet extraordinaire de l’UA à son siège à Addis Abeba, avec la participation au plus haut niveau de tous les États membres. Certes, un rapport seul ne résoudra pas les défis, nombreux, qui interpellent le continent. Ce n’est, au fond, qu’un document. Mais sa valeur réside dans l’élan qu’il peut susciter, s’il est bien conçu, captivant notamment les imaginaires, bien porté, et suivi d’effets.

Dans cette entreprise de renouveau, l’UA doit occuper une place centrale. En tant que cadre institutionnel légitime de l’unité continentale, elle est l’entité la mieux placée pour incarner la voix et les ambitions collectives de l’Afrique. Il faudra à cet égard inverser une tendance préoccupante, celle qui voit des sommets organisés avec des partenaires extérieurs attirer davantage de chefs d’État et de gouvernement que les propres assises de l’organisation continentale.

En mai 1963, lors du débat qui, à Addis-Abeba, opposa les tenants d’une approche graduelle de l’unité africaine à ceux qui plaidaient pour une intégration politique plus poussée dès le départ, Kwame Nkrumah eut sans doute le tort – politique – d’avoir eu raison trop tôt. L’histoire, cependant, a rétroactivement validé sa vision: les limites de l’approche qui prévalut à la création de l’OUA sont aujourd’hui manifestes, et les retards accumulés pèsent lourdement sur les perspectives du continent. Il appartient désormais aux dirigeants africains actuels de rendre justice à cette intuition visionnaire – fût-ce avec plusieurs décennies de retard.

*Said Djinnit a été Directeur de Cabinet de Salim Ahmed Salim (de 1989 à 1999), avant d’occuper par la suite les fonctions de Secrétaire général adjoint aux Affaires politiques de l’OUA et celles de Commissaire à la Paix et à la Sécurité à l’UA. De 2008 à 2019, il a été Représentant spécial du Secrétaire général des NU en Afrique de l’Ouest, puis Envoyé spécial du Secrétaire général dans la région des Grands Lacs.

**Dr. Ibrahim Assane Mayaki a été Directeur général de l’Agence de Développement de l’UA (AUDA-NEPAD) de 2009 à avril 2022. De 1997 à 2000, il a assumé les fonctions de Premier ministre de la République du Niger et de Ministre des Affaires étrangères.

***El-Ghassim Wane a été Directeur du Département paix et sécurité à la Commission de l’UA et Directeur de cabinet du Président de la Commission de l’UA. Il a aussi servi comme sous-Secrétaire général des NU chargé du maintien de la paix et Représentant spécial du Secrétaire général au Mali et chef de la MINUSMA.

Consultation with the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights

Consultation with the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights

Date | 18 June 2025

Tomorrow (19 June), the African Union (AU) Peace and Security Council (PSC) will convene its 1284th session for a consultation with the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights (ACHPR).

Following opening remarks by Innocent Shiyo, Permanent Representative of Tanzania to the AU and Chairperson of the PSC for June, Bankole Adeoye, AU Commissioner for Political Affairs, Peace and Security (PAPS), is expected to deliver a statement. The Chairperson of the ACHPR is expected to deliver a briefing to the PSC on the work of the ACHPR as it relates to peace and security.

The consultative meeting is being convened in line with Article 19 of the PSC Protocol, which calls for close cooperation between the PSC and the ACHPR in advancing peace, security, and stability across Africa. Beyond the Protocol’s provision, the PSC, at its 866th session, agreed to institutionalise this engagement by holding annual joint consultative meetings with the ACHPR. This commitment to regular engagement is grounded in the broader legal mandates that define and reinforce the complementary roles of the PSC and ACHPR in promoting peace, security, and human rights on the continent. The two organs of the AU are both entrusted, under their respective legal frameworks, with advancing peace, security, and human rights across the continent. The PSC Protocol, under Article 3(f), outlines the Council’s responsibility to uphold human rights as an essential part of preventing conflict. Similarly, Article 45 of the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights mandates the ACHPR to promote and protect the rights of individuals and communities. Additionally, Article 23 of the African Charter affirms that all people have a fundamental right to live in peace and security, both within their countries and globally. These provisions establish a shared legal and normative foundation for collaboration between the PSC and ACHPR in addressing peace and security challenges on the continent.

These consultative meetings have been held regularly since 2019; however, they were interrupted over the past three years. The most recent meeting took place in August 2021 during the Council’s 1019th session. The communiqué from that session underscored, among other key points, the vital importance of mainstreaming human rights throughout all phases of conflict prevention, management, resolution, stabilisation, and post-conflict reconstruction and development. In this context, it would be of interest to members of the PSC to explore how to operationalise this commitment, including through the engagement of specific mechanisms of the ACHPR, such as the Focal Point on Human Rights in Conflict Situation in between the consultative sessions between the two sides.

During tomorrow’s session, the ACHPR is expected to brief the PSC on its recent efforts related to country-specific conflict situations. This may also include violations being reported to the ACHPR in relation to countries that are preparing for elections.

In terms of specific conflict situations, a key item the PSC is expected to be briefed on concerns the Joint Fact-Finding Mission to Sudan led by the ACHPR. In response to the PSC’s request during its 1213th session in May 2024 for an investigation into the human rights situation in El Fasher and other parts of Darfur, the ACHPR launched a hybrid Fact-Finding Mission to examine violations against civilians since the outbreak of the conflict. As explained during a press conference given by the ACHPR, the mission covers a wide range of issues, including civil and political rights (such as arbitrary detention and suppression of freedoms), economic and social rights (such as denial of access to food, healthcare, and education), environmental and property rights, and grave abuses like torture, sexual violence, and attacks on civilians. To support its investigation, the Commission invited written and oral testimonies from individuals and organisations, in which the submission window officially closed on 28 March 2025. Through this process, the ACHPR collected documentation on the kind of violations that took place in the course of the war.

In light of the ongoing crisis and the Commission’s initial findings, the ACHPR has taken further steps to strengthen its engagement through the extension of the mission’s mandate. The most recent ACHPR Resolution, ACHPR/Res.635 (LXXXIII) 2025, decided to extend the mandate of the Joint Fact-Finding Mission for an additional period of six (6) months, starting on 3 May 2025. The PSC is therefore expected to receive an update on the progress of the mission, including insights from virtual investigations, the extension of its mandate, and the ongoing challenges and opportunities for field deployment.

Regarding the ongoing deterioration of the human rights situation in eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), the Commission is expected to update the PSC based on its Resolution ACHPR/Res.627 (LXXXII) 2025. This resolution highlights serious violations, including the destruction of camps for internally displaced persons, widespread sexual violence against women and girls, the recruitment and use of child soldiers, targeted assassinations, the burning of prisons, and the widespread collapse of social and economic infrastructure. It called on the DRC to end impunity by bringing perpetrators to justice and implored the AU and regional bodies to step up their efforts to bring an end to the long-protracted conflict.

The ACHPR is also anticipated to brief the PSC on the grave human rights situation in South Sudan, particularly in light of escalating violence and political instability in Upper Nile State and Nasir County. Drawing from its 11 March 2025 press statement, the ACHPR is likely to highlight concerns such as the arbitrary detention of political actors within the transitional government and the loss of civilian lives resulting from the ongoing unrest. It called for a) cease-fire and de-escalation; b) inclusive dialogue between the signatories of the Revitalised Agreement on the Resolution of the Conflict in South Sudan; c) ensuring the protection of civilians; and d) accelerated implementation of the transitional process.

Hence, building on these country-specific developments, the consultative meeting presents an opportunity for the PSC to receive rich perspectives on how to reinforce its approach to these individual conflict situations, drawing on these engagements of the ACHPR.

The ACHPR briefing may also cover thematic issues. These may include the protection of civilians in armed conflict, with a particular focus on vulnerable groups such as women, children, internally displaced persons (IDPs), and persons with disabilities. To this end, the Commission’s Resolution ACHPR/Res.513 (LXX), explicitly condemned attacks on IDP camps and urged States to uphold their civilian character and prosecute perpetrators. The Commission is also expected to spotlight the persistent and escalating use of sexual and gender-based violence as a tactic of war. This concern has been consistently addressed through its Focal Point on Conflict and the Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Women, such as Resolutions ACHPR/Res. 283 (2014) and ACHPR/Res. 365 (2017), and in its monitoring of conflict situations such as Boko Haram-affected areas and South Sudan. Another key thematic area likely to be addressed is the accountability gap for grave human rights violations and the urgent need to strengthen transitional justice mechanisms in line with the African Union Transitional Justice Policy. The ACHPR’s 2018 Study on Transitional Justice and Human and Peoples’ Rights in Africa provides a comprehensive African Charter–based framework for promoting truth, reparations, and legal redress, complementing the African Union Transitional Justice Policy. Furthermore, the Commission may raise emerging concerns related to the human rights implications of militarisation, the misuse of emergency powers, and the obstruction of humanitarian access, particularly in protracted and complex crises.

Lastly, in tomorrow’s consultations, it is expected that the two organs will revisit and follow up on key previous decisions. The communiqué adopted during the PSC’s 866th session set out concrete modalities aimed at strengthening and sustaining collaboration with the ACHPR. These include the establishment of a structured mechanism for regular information exchange—particularly through the incorporation of ACHPR’s relevant outputs into the Continental Early Warning System (CEWS); periodic briefings to the PSC between annual joint sessions, focusing on the human rights dimensions of specific conflict situations or cross-cutting thematic issues; and consistent interaction between the PSC Chairperson and the ACHPR, either through the Commission’s Chairperson or its designated Focal Point on Human Rights in Conflict Situations. These mechanisms are designed to ensure the systematic integration of human rights into the PSC’s peace and security work. However, such engagements have not been actively pursued in recent years. Tomorrow’s session, therefore, offers an opportunity to revive and operationalise these collaborative mechanisms.

The expected outcome of the session is a communiqué. The PSC may reiterate its commitment to strengthening collaboration with the ACHPR and, in doing so, emphasise the establishment of a formal coordination mechanism between the PSC Chairperson and the ACHPR Chairperson or its designated Focal Point on Human Rights in Conflict Situations to enable timely communication and decision-making on urgent human rights concerns in conflict-affected contexts. To enhance the integration of human rights in peace and security responses, the PSC may encourage the systematic mainstreaming of human rights across all phases of conflict prevention, management, resolution, and post-conflict recovery, including through the incorporation of ACHPR analyses and outputs into PSC deliberations. In this regard, the Council may underscore the importance of integrating ACHPR findings and resolutions into the Continental Early Warning System to strengthen early warning capabilities through the use of human rights indicators, particularly in high-risk countries and regions. Concerning the Joint Fact-Finding Mission on Sudan, the PSC may endorse its continuation and adequate resourcing, and encourage facilitation of field deployment where security conditions permit. Furthermore, the PSC may stress the need to address the root causes and structural drivers of armed conflict on the Continent, urging Member States and relevant stakeholders to adopt inclusive, rights-based approaches to conflict resolution—emphasising dialogue, negotiation, mediation, and context-specific transitional justice mechanisms that promote accountability, reconciliation, and sustainable peace. In this respect, the Council may encourage Member States to establish or reinforce domestic transitional justice mechanisms in alignment with continental human rights and justice frameworks. The PSC may also highlight the importance of receiving regular briefings from the ACHPR through its special mechanisms such as the country rapporteurs, the Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Women, the Focal Point on Human Rights in Conflict Situations and the Special Rapporteur on Refugees, Internally Displaced Persons and Asylum Seekers. The communique may also reiterate the outcomes of the previous consultative meetings and call for the adoption of a program of action for the operationalisation of the concrete measures identified in the communiques of the 866th, the 953rd, and the 1019th sessions.