Update on the situation in South Sudan

Update on the situation in South Sudan

Date | 11 June 2025

Tomorrow (12 June), the African Union (AU) Peace and Security Council (PSC) will convene its 1283rd session to receive an update on the situation in South Sudan.

Following opening remarks by Innocent Shiyo, Permanent Representative of Tanzania to the AU and Chairperson of the PSC for June, Bankole Adeoye, AU Commissioner for Political Affairs, Peace and Security (PAPS), is expected to deliver a statement. Joram Mukama Biswaro, Special Representative of the Chairperson of the AU Commission for South Sudan and Head of the AU Liaison Office in Juba; Ismail Wais, IGAD Special Envoy to South Sudan and representatives from the AU Panel of the Wise and AU Ad-Hoc Committee for South Sudan (C5) are also expected to deliver briefings. The representative of South Sudan, as a country of concern, is also expected to make a statement.

The session follows the Council’s 1265th and 1270th sessions on South Sudan, held on 18 and 31 March respectively, in response to the sharp deterioration in South Sudan’s political and security landscape since renewed violence erupted on 4 March. The 4 March attack on the South Sudan People’s Defence Force (SSPDF) base in Nasir by the militia group known as the White Army that is reportedly loosely associated with First Vice President Riek Machar the leader of the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement- In Opposition (SPLM-IO), has triggered the most severe crisis facing the Revitalised Agreement on the Resolution of the Conflict in South Sudan (R-ARCSS) since its adoption in 2018. The situation has since devolved into military confrontations, high-level arrests, deployment of Ugandan troops and increased violence. These developments have gravely undermined the transitional process.

Tensions had been mounting even before the 4 March incident, largely due to the breakdown of relations in the presidency and a series of unilateral actions. These included replacing opposition officials with loyalists and reshuffling positions within his own faction, the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement (SPLM). Since February 2025, more than 20 senior SPLM/A-IO political and military officials have been arrested, while many others have gone into hiding or fled the country, further deepening the rift between Kiir and Machar. Governors in at least three states loyal to Machar have also been replaced.

The unstable political situation spiralled further down when the government arrested Machar on 26 March in Juba—a move his party denounced as marking the collapse of the 2018 peace agreement, which ended a devastating five-year civil war that claimed nearly 400,000 lives. The move was widely condemned, including by the PSC’s 1270th session press statement, which called for Machar’s ‘immediate and unconditional release’ and urged the government to uphold his safety and health.

Apart from the constitutional crisis it has triggered for the Government of National Unity under the R-ARCSS, Machar’s detention also instigated a rapid unravelling of the SPLM-IO’s cohesion. Reports indicate that key party figures, including Deputy Chairperson Oyet Nathaniel, fled or went into hiding, while internal disputes escalated into factionalism. Internal rifts within the SPLM-IO erupted publicly in April 2025 when Deputy Chairman Oyet Nathaniel, who is also the first deputy speaker of parliament, suspended four senior members of the party, including Peacebuilding Minister Stephen Par Koul, for allegedly plotting to replace Machar. In response, a convening of a faction of SPLM-IO members in Juba on 9 April announced the establishment of a temporary leadership structure that will cease upon Machar’s release and named Koul as the interim chairperson of the party. Despite the PSC’s firm position calling for Machar’s immediate and unconditional release, Juba did not heed this call. Machar and other political and military leaders from the SPLM-IO remain in detention.

Further compounding the difficult political situation is the major changes in the leadership of the ruling SPLM that President Kiir chairs. In a move that is widely seen to be an orchestration of a succession plan, President Kiir took steps to elevate his former financial advisor, Benjamin Bol Mel, to very senior positions. First, he appointed Bol Mel to the position of vice president of the country. Most recently, on 21 May, after dismissing James Wani Igga, a long-serving liberation struggle stalwart, Kiir appointed Bol Mel to be the first vice chairman of the ruling SPLM, a position that is viewed to be a launching pad to the presidency.

The security situation has also deteriorated markedly. Across Upper Nile and other hotspots, clashes between the SSPDF and SPLM-IO forces have intensified, resulting in widespread civilian displacement and the destruction of critical infrastructure, including the 3 May aerial bombing of a Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) hospital. The AUC Chairperson, Mahmoud Ali Youssouf, condemned the attack, which he described as ‘a flagrant breach of International Humanitarian Law’ and urged for an investigation. The UN Commission on Human Rights in South Sudan also warned the attacks ‘could amount to a war crime.’ The gravity of the situation in South Sudan is further underscored by recent UNHCR data indicating that over 165,000 have fled since the resurgence of violence in March, with over 100,000 people seeking refuge in neighbouring countries.

While Uganda’s military deployment in South Sudan is under a bilateral agreement for training and technical support and positions Uganda in shaping the political and security trajectory in South Sudan including as one of the guarantors of the R-ARCSS, there are concerns that Uganda’s presence tips the balance firmly in favor of President Kiir and away from SPLM-IO and may trigger militarised external interference on the side of SPLM-IO. The SPLM-IO also accuses Ugandan forces of participating in military operations, hence in a manner contrary to the R-ARCSS.

Given that the implementation of the R-ARCSS was already derailed, the current situation is feared to deal a mortal blow to the transitional process. In his briefing to the extraordinary summit of the Inter-Governmental Authority on Development (IGAD) on South Sudan held on 12 March, the Executive Secretary of IGAD warned that ‘should tensions escalate, the risk of a return to widespread hostilities looms large, with repercussions that would echo resoundingly across the region.’ In his 16 April briefing to the UN Security Council, Nicholas Haysom, Special Representative of the Secretary-General and Head of UNMISS described the conditions as ‘darkly reminiscent of the 2013 and 2016 conflicts, which took over 400,000 lives’ and warned of a trajectory that could shift from community-based violence to ‘a more complex picture involving signatory parties and foreign actors.’ He also flagged the intensifying use of hate speech and misinformation, which continue to fuel ethnic tension and violence.

In response to the growing crisis, regional and international actors have ramped up diplomatic efforts despite minimal breakthroughs. On 29 March, the AUC Chairperson, Mahmoud Ali Youssouf and UNSG António Guterres discussed the evolving situation in South Sudan. They reaffirmed their support for the R-ARCSS as the best path to lasting peace in South Sudan and agreed to coordinate efforts between the AU, IGAD, and the UN.

The PSC’s 1265th and 1270th sessions had called for the AU Commission Chairperson to deploy a high-level delegation to engage the parties in South Sudan. Led by former Burundian President Domitien Ndayizeye, the AU Commission Chairperson, Mahmoud Ali Youssouf, deployed the AU Panel of the Wise to Juba on 2 April. The delegation held meetings with various stakeholders, including President Kiir, but was reportedly denied access to Riek Machar. It is expected that tomorrow’s session will consider the Panel’s report of the visit.

The Panel’s visit was followed by a joint AU–IGAD high-level visit from 5–6 May, during which the AU Commission Chairperson and the IGAD Deputy Executive Secretary met with South Sudanese leaders to reaffirm support for the R-ARCSS and preserve its hard-won gains and reiterate support for the timely, credible, and transparent implementation of the transitional roadmap. Yet again, the Chairperson did not get access to Machar.

More recently, on 8 May, the Quartet – AUMISS, IGAD, UNMISS and RJMEC- issued a joint statement urging an immediate cessation of hostilities, the release of detainees, and the revitalisation of the R-ARCSS. The statement welcomed the recent joint visit by the AUC and IGAD to South Sudan and highlighted that the 2018 peace deal remains the only viable framework for resolving the crisis. The Quartet, also called the reinvigoration of the ‘visibly stalled peace implementation by addressing all grievances through an inclusive political dialogue’, with the release of the First Vice President and other SPLM/A-IO officials as the starting point.

From 3 – 4 June, IGAD convened a consultative meeting bringing together regional and international envoys, including representatives from the AU, UNMISS, and the C5, to address South Sudan’s peace process. The discussions aimed to identify viable solutions to de-escalate tensions and reinforce support for the Revitalised Agreement on the Resolution of the Conflict in South Sudan (R-ARCSS), emphasising the need for coordinated efforts to sustain stability and advance the country’s transitional roadmap. (A consolidated overview of key developments, policy positions and diplomatic engagements can be accessed via Amani Africa’s regularly updated Tracker of events and diplomatic efforts on the crisis in South Sudan)

Apart from following up on its proposed policy measures from previous sessions, tomorrow’s session is expected to help the PSC take stock of both the political and security developments on the one hand and the diplomatic efforts underway, including the steps taken by the AU. Building on the mission of the Panel of the Wise and the joint AU-IGAD visit, the statement of the Quartet may help structure PSC’s deliberations on additional steps to be taken to arrest the deteriorating situation and put the transitional process in South Sudan back on track. Undeniably, for any initiative of the PSC, the role of the region and most notably Uganda, with its presence on the ground and its role as Guarantor, is expected to be paramount.

The expected outcome of the session is a communique. The PSC may reiterate that the R-ARCSS remains the most viable and relevant Agreement for sustainable peace and stability in South Sudan. The PSC may call for immediate and unconditional cessation of hostilities and restoration of strict adherence to the permanent ceasefire, with IGAD’s Ceasefire and Transitional Security Arrangements Monitoring and Verification Mechanism (CTSAMVM) reinforced to ensure compliance. Echoing the Quartet, the PSC may also call for the full and scaled-up return to and implementation of the R-ARCSS and the transitional process with the full and effective participation of the signatories of the R-ARCSS. To this end, the Council may reiterate its demand for the release of detained politicians, including First Vice President Riek Machar. The PSC may also call for the streamlining and coordination of diplomatic efforts. The PSC may request the AU Commission Chairperson to task a head of state of an AU member state to work with the guarantors of the R-ARCSS and the Committee of 5 to facilitate dialogue between the leaders of the main signatories of the 2018 agreement to restore mutual confidence and culminate in a joint public declaration affirming their commitment to peace.

The funding of the AU from member states is a ‘farce’, Mo Ibrahim

The funding of the AU from member states is a ‘farce’, Mo Ibrahim

Date | 10 June 2025

Solomon Ayele Dersso, PhD

Founding Director, Amani Africa

The issue of the poor state of self-financing of the African Union (AU) once again came into the spotlight. During the annual Mo Ibrahim Governance Weekend (IGW) event held from 1-3 June in Marrakech, the Kingdom of Morrocco, in a conversation with Mo Ibrahim, founder of the Mo Ibrahim Foundation, the former AU Commission Chairperson, Moussa Faki Mahamat in the plenary of the annual event told Ibrahim that the AU depended on external donors for about 70 per cent of its funding.

Ibrahim expressed his dismay about AU’s excessive dependence, stating that ‘70% of the 650 million annual budget of the AU is funded by foreigners is a farce.’ Faki agreed and added that ‘it is actually frustrating.’ Instructively, in an exclusive interview for Amani Africa’s podcast, The Pan Africanist, the new AU Commission Chairperson, Mohamoud Ali Youssouf, identified the issue of financing as a major priority area for his chairship of the AU Commission.

The deserved public criticism of the failure of African leaders to fund the AU comes as the AU’s landmark decision towards enhancing self-financing marks its ten-year anniversary this June. As part of her consequential tenure that set in motion the pioneer initiatives of AU’s Agenda 2063, including the AfCFTA, one of the issues that Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma championed was to address the perennial challenge of heavy dependency on external sources in the financing of the AU. It culminated in two key policy decisions.

AU member states’ Johannesburg and Kigali ambitions

The first was the June 2015 summit held in Johannesburg, South Africa, where the AU Assembly adopted a decision, Assembly/AU/Dec.578 (XXV) on the Scale of Assessment and Alternative Sources of Financing of the AU. One of the major commitments that AU member states made under Assembly decision 578 was to fund 100 per cent of the operational budget, 75 per cent of the program budget and 25 per cent of the AU’s peace operations budget.

The second was the July 2016 Kigali summit that settled the question of the sourcing of the funds for realising the decision adopted in Johannesburg. Accordingly, the Kigali AU summit adopted Assembly/AU/Dec.605(XXVII) decision which committed to ‘institute and implement a 0.2 per cent levy on all eligible imported goods into the Continent to finance AU Operational, Program and Peace Support Operations Budget starting from the year 2017.’

AU’s non-implementation malady

Signifying the fast-expanding gulf between the ambitions of AU summit outcomes and the realities of acting on such outcomes, the Johannesburg and Kigali decisions have faced the same fate as other decisions of the AU – non-implementation. This malady of non-implementation that became prominent during Faki’s tenure promoted him to lament during his address of the opening of the February 2024 AU summit that ‘the frantic tendency to make decisions without real political will to implement them, has grown to such an extent that it has become devastating to our individual and collective credibility.’

As a result, little progress has been made in the ambition of the financial reforms introduced since Johannesburg to ensure financial autonomy and reduced dependency and secure timely, adequate, reliable and predictable payments by member states of their assessed contributions.

The story that the 2025 AU budget tells

The 2025 budget of the AU, adopted during the 45th ordinary session of the Executive Council held in Accra, Ghana in July 2024, was US$608,248,415. Of these, the regular budget was at US$555,319,415. The operational budget to which AU member states contributed 98 per cent, short of 2 per cent from the Johannesburg target, was only 167,045,485. By contrast, AU member states, along with African institutions and internal sources, covered only 22.5 % of the US$ 388,273,929 programme budget of the AU. While this represents a notable increase from the less than 6 per cent contribution of member states to the programme budget in 2015, it is a far cry from the Johannesburg target, which member states committed to realise by 2025. Considering the significance of the programme budget for advancing the major AU objectives, the failure to meet the Johannesburg target is emblematic of the growing gulf between the policy ambitions of the AU and its actual performance.

When it comes to member states’ contribution to peace operations, the lack of progress becomes even more glaring. The July 2024 Executive Council decision (EX.CL/Dec.1265(XLV) carrying the 2025 budget indicated that ‘peace support operations with a budget of US$52,929,131’ was ‘funded by International Partners.’

What emerges from the 2025 AU budget is that the AU has met the Johannesburg target only in relation to its operational budget. The portion of member states’ contribution to the overall AU budget renders the distance between the Johannesburg target and where the AU stands today stark. The overall budget of the AU for 2025, as captured in the July 2024 Executive Council decision, puts the balance of contributions between AU member states and partners at 32.9 per cent and 58.1 per cent, respectively.

Explaining the ‘farce’ that is the state of AU’s self-financing

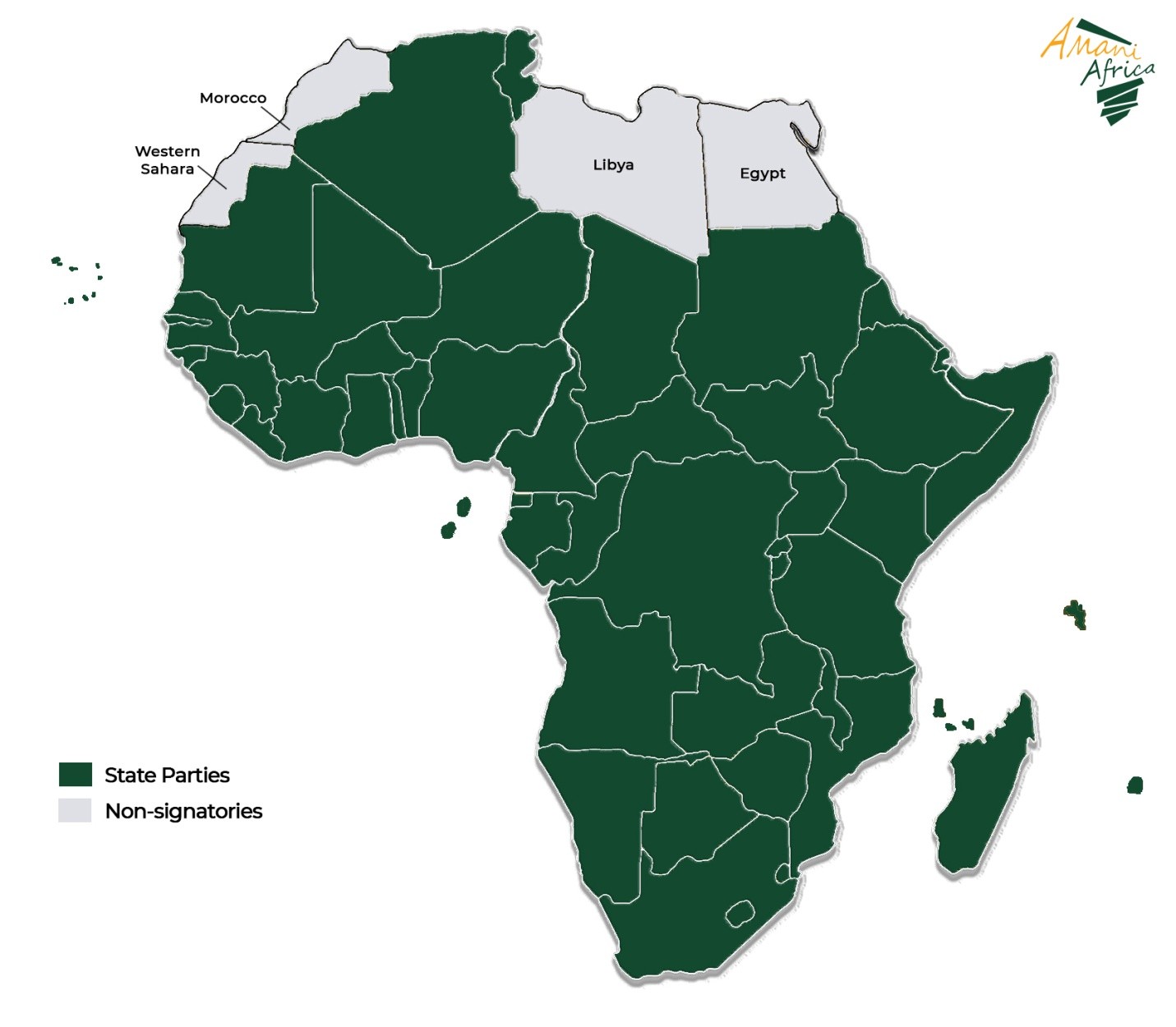

A major factor behind this dismal state of the self-financing of the AU is the non-implementation of the Kigali AU summit decision. In 2018, the AU reported that only 16 of the AU member states were implementing the Kigali decision of collecting the 0.2 levy. Between that time and 2025, that number increased by only one.

Another major factor that impeded the growth of member states’ contribution to programme operations budgets was the 2019 decision of the AU capping member states’ contribution at $250 million. The result of this capping is that much of the member states’ contribution ends up funding the operational budget and leaving only small portion of as the remaining balance for the programme budget.

Additionally, despite the ambition of the AU’s financial reform to move away from reliance on a few member states, the AU did not succeed in achieving this ambition. As such, the continuing reliance on a few countries constrains the scope for expanding the contribution of member states for achieving ownership. The AU Commission Chairperson, Youssouf, told The Pan Africanist that the formula for mobilising the contributions of member states has created heavy reliance on a few countries. As he put it, ‘we need to think about a better sharing of the burden (of AU financing) …we have to look into the formula again.’

Further compounding the dismal state of the financing of the AU is the negative growth of member states’ contributions since the time of COVID-19. As the AU Commission Deputy Chairperson, Selma Haddadi, reminded members of the PRC in her address to the opening of the 50th ordinary session of the Permanent Representatives Committee (PRC) of the AU on 9 June 2025, ‘the African Union’s approved budget has experienced a negative growth rate of 6 per cent, despite the establishment of new organs and the expansion of its mandates.’ She went on to note that ‘[a]lthough Member States’ contributions have been capped at US$250 million since 2019, actual assessed contributions have consistently fallen short of this ceiling.’ In fact, the statutory contribution of member states was capped at $200 million for 2025.

There is also the issue of delay or non-payment of assessed contributions on time and in full. Following the adoption of the three-tier sanctions regime in 2018 on payment of assessed contributions and the follow-up of the sanctions regime, the payment of member states has improved significantly. However, the fact that a significant number of member states, including major contributors, effect payment as late as the middle of the year represents a challenge. For the 2024 budget, the AU Ministerial Committee on Scale of Assessment reported that 13 member states did not pay into the 2024 regular budget, and a further five member states made only partial payment as of 31st December 2024.

The price AU is paying for the poor state of its funding

The dismal state of progress in meeting the Johannesburg targets entails dire consequences for the functioning of the continental body. As the Deputy Chairperson pointed out, apart from perpetuating heavy reliance on external funding and thereby differing the ambition of ownership, the funding challenge significantly constrained the AUC’s capacity to effectively implement the decisions of the Policy Organs and strategic priorities.’ Additionally, this funding constraint, Haddadi pointed out, ‘has significantly hindered the effective implementation of security and safety standards.’

AU Commission Deputy Chairperson invited member states to provide ‘guidance on the immediate way forward’ and engage in ‘reflection on this critical issue of the financial sustainability of our Union and its impact on our operations.’ In his exclusive interview with The Pan-Africanist Chairperson Youssouf, apart from proposing the revisiting of the burden sharing, he emphasised the need for other sources of financing such as the private sector and innovative finance sources.

Enter the new AU Commission leadership

Signifying the attention the new AU leadership attaches to this issue, during the opening session of the 50th Ordinary Session of the PRC, the financing woes afflicting the AU took prime place in the speech of the Deputy Chairperson (DCP) of the AU Commission. One third of the speech was dedicated to this issue.

The new AU Commission leadership is on target in prioritising the issue of the funding of the AU. ‘In (my) vision,’ the Chairperson told The Pan Africanist, ‘the mobilisation of resources is central.’ Echoeing Mo Ibrahim’s comments, Youssouf noted that ‘You can not envisage… the possibility …of ownership of the programmes while waiting the support of partners’.

It will be quite a success if this focused prioritisation of addressing the challenge of AU funding by the new AU Commission leadership leads to enabling member states to deliver on the long-delayed commitment of funding at least 75 per cent of the programme budget of the AU. While one hopes that Youssouf and Haddadi succeed in this quest, it remains to be seen how they will catalyse the required collective will of member states for overcoming the ‘farce’ that is the funding of the AU.

The content of this article does not represent the views of Amani Africa and reflect only the personal views of the authors who contribute to ‘Ideas Indaba’

Update on the activities of the Multinational Joint Task Force (MNJTF) and consideration of the Regional Strategy for Stabilisation, Recovery, and Resilience (RS-SRR)

Update on the activities of the Multinational Joint Task Force (MNJTF) and consideration of the Regional Strategy for Stabilisation, Recovery, and Resilience (RS-SRR)

Date | 9 June 2025

Tomorrow (10 June) the African Union (AU) Peace and Security Council (PSC) will convene its 1282nd session to receive an update on the activities of the Multinational Joint Task Force (MNJTF) and review the implementation of the Regional Strategy for Stabilisation, Recovery, and Resilience (RS-SRR) in the Lake Chad Basin.

Following opening remarks by Innocent Shiyo, Permanent Representative of Tanzania to the AU and Chairperson of the PSC for June, Bankole Adeoye, AU Commissioner for Political Affairs, Peace and Security (PAPS), is expected to deliver remarks. Statements are also expected from Hycinth Banseka, Technical Director of the Lake Chad Basin Commission (LCBC) on behalf of the Executive Secretary of the LCBC and Godwin Michael MUTKUT, Multinational Joint Task Force (MNJTF) Commander.

Tomorrow’s session follows the PSC’s 1254th meeting on 13 January 2025, convened to consider the AUC Chairpersons report on the activities of the MNJTF against Boko Haram where the Council renewed the MNJTF’s mandate for an additional 12 months and requested the AU Commission and the LCBC Secretariat to regularly report to the Council on the activities of the Force. The session emphasised enhanced diplomatic engagement, particularly with Niger, to strengthen regional counter-terrorism efforts. It also brought attention to the need for strengthening coordination and effective participation of MNJTF contributing countries and in this respect, it tasked the Lake Chad Basin Commission to continue engaging Niger to ensure its full return and cooperation with the Force and to promote a comprehensive, multi-sectoral and inclusive approach and civil-military cooperation for creating conditions for return of displaced persons. Tomorrow’s session is expected to build on these priorities, with a particular focus on operational developments, prevailing security dynamics, and the status of the implementation of the RS-SRR, notably the review and updating of the strategy.

The Lake Chad Basin, encompassing Cameroon, Chad, Niger, and Nigeria, remains a region of complex security, humanitarian, and developmental challenges, largely driven by the activities of Boko Haram and its factions, including the Islamic State West Africa Province (ISWAP) and Jama’atu Ahlis Sunna Lidda’awati wal-Jihad (JAS). The MNJTF, comprising troops from the Lake Chad Basin Commission (LCBC) member states and Benin, remains a critical regional coalition serving as the security instrument in countering the threats posed by these groups. The Force has reportedly facilitated the return of over 3,800 internally displaced persons (IDPs) and 2,306 refugees in 2024 alone.

However, despite significant military successes by the MNJTF, the terror groups continue to pose a threat through asymmetric tactics such as the use of improvised explosive devices (IEDs), suicide attacks, abductions and attacks on civilian and military targets. In one such recent major attack, on 25 March, Boko Haram is reported to have killed at least 20 Cameroonian soldiers in an attack on a military base in the Nigerian border town of Wulgo.

One of the issues expected to feature during tomorrow’s session concerns the operational challenges facing MNJTF. Despite ongoing support from the AU and partners, the MNJTF continues to face capability gaps that undermine the effectiveness of its counterterrorism operations, such as a lack of appropriate counter-IED equipment. IEDs, particularly those placed along main supply routes, accounted for approximately 60% of MNJTF casualties in 2024. The unavailability of sophisticated IED detectors has delayed troop movements and places both civilian convoys and military convoys at risk. The absence of a dedicated attack aircraft has also left the force reliant on TCCs national air forces, delaying approvals and undermining the force’s ability to mount coordinated air-ground operations. Considering that terrorist forces have begun using surveillance drones to monitor MNJTF movements, the Force’s lack of anti-drone technology or jamming systems reduces its operational advantage and leaves it vulnerable to enemy intelligence.

As highlighted in respect to the PSC’s 1254th session, another major challenge for the MNJTF is the continued presence of terrorist groups on the islands of Lake Chad. As reported back then, the 4th Lake Chad Basin Governors’ Forum identified as a major challenge the need ‘to clear remnants of Boko Haram fighters from their bases on the Tumbuns (islands on the fringes of the Lake Chad) from which they continue to launch attacks on the surrounding areas and beyond. The Tumbuns serve as their logistics hub, secure havens, and staging grounds. Their occupation of these islands also facilitates their generation of funds through illegal fishing and farming activities.’ In this respect, the 5th Lake Chad Basin Governors’ Forum held late in January 2025 called for ensuring that ‘member states effectively occupy the Lake Chad islands as a means of strengthening transboundary security, with a focus on securing and controlling waterways.’

Another issue is the follow up on PSC’s decision on ensuring the participation of Niger in the MNJTF. Although the initial interruption of Niger’s participation in MNJTF following the coup of June 2023 was restored owing to engagement from Nigeria, in March 2025 Niger announced its withdrawal from MNJTF. Apart from political dynamics, it appears that withdrawal of support for Niger might have played a role. The Communique of the Lake Chad Basin 5th Governors Forum for the Regional Cooperation on Stabilisation, Peacebuilding and Sustainable Development, thus ‘noted with concern the suspension of donor support for Niger’s National Window of the Regional Stabilisaiton Facility (RSF), which could negatively impact progress across the region.’

It is feared that Niger’s withdrawal will weaken the MNJTF and create a security vacuum that the terrorist groups operating in Lake Chad could take advantage of. The void from Niger’s withdrawal coupled with the influx of militants and weapons from the Sahel and ISIS networks in North Africa, poses threat to the gains made under the MNJTF. It is also worth recalling that the death of 40 Chadian soldiers in a terrorist attack on a military base in Chad’s border region with Nigeria last December prompted Chad’s President Mahamat Idriss Déby to threaten possible withdrawal from the MNJTF as well. During tomorrow’s session, it would be of interest for PSC members to get clarity on the implications of Niger’s withdrawal for the MNJTF and how any adverse impact of the withdrawal can be mitigated.

The other issue that the PSC is expected to discuss during tomorrow’s session is the regional stabilisation strategy. The RS-SRR, endorsed by the PSC during the 816th session held on 5 December 2018 and entered its second phase in 2024, complements the MNJTF’s military efforts by addressing the structural drivers of conflict through addressing broader governance, humanitarian, and development challenges. The strategy, implemented across eight targeted territories in the four LCBC states, has facilitated community reconstruction, market reactivation, and the reintegration of former combatants. Following the revision of the RS-SRR for 2025 – 2030 at the 5th steering committee meeting on 20 September 2024, with updated Territorial Action Plans (TAPs) and a Community-based Reconciliation and Reintegration Policy to enhance its effectiveness, the 70th Ordinary Session of the LCBC Council of Ministers held in Niamey, Republic of Niger on 27 February 2025 adopted the revised strategy. The revised strategy seeks to shift focus from stabilisation efforts to sustained stability and puts greater emphasis on socio-economic development on the basis of the security, humanitarian and development nexus approach. The LCBC Council of Ministers also directed the Executive Secretariat to revise the Territorial Action Plans (TAPs) and develop a Regional Transitional Justice Policy.

The communiqué of the 5th Lake Chad Basin Governors’ Forum, among others, encouraged the PSC to endorse the adjusted RS-SRR. Tomorrow’s session will thus provide an opportunity for the PSC to assess progress on the implementation of the strategy and consider the updated RS-SRR for endorsement. The PSC is also likely to reiterate its 1207th session call for the states to develop National Action Plans in line with UN Security Council Resolutions (UNSCR) 2250 and 2419, and to operationalise these two UNSC Resolutions through the revised TAPs, in order to ensure that the implementation of the revised RS SRR effectively addresses the structural root causes of the conflict.

Sustained reintegration of returnees and fighters that deserted the terror groups requires stronger investment in infrastructure, education and livelihoods. In the report to the PSC in January 2025, the AU Commission Chairperson noted that ‘[w]hile the number of resettled populations have continued to rise, most of these communities received little or no form of humanitarian assistance, and there is a need for urgent actions to enhance the livelihoods of these resettled communities.’ Environmental degradation, exacerbated by climate change, compounds these challenges and increases community vulnerability.

The expected outcome of the session is a communique. The Council is expected to endorse the revised RS–SRR and call on member states to align their national plans with the revised strategy. The PSC may underscore the need for enhancing close coordination and commitment of MNJTF member states and for continuing to engage in Niger on collaboration in addressing the collective threat posed by terrorist groups in the region. The PSC may also call for fortifying the capabilities of the MNJTF, including by equipping the mission with anti-drone technology or jamming systems to address the threat posed by the deployment of drones from terrorist groups. The Council may also wish to follow up on its 1207th decision to undertake a solidarity field mission to the Lake Chad Basin. The PSC may call on AU and LCBC to mobilise additional support to the MNJTF, particularly in terms of enhancing its anti-IED and amphibious and naval capabilities. The PSC may underscore the need for climate change sensitive programming and provision of rehabilitation support for affected regions and communities. The PSC may emphasise the importance of enhancing collaboration between the MNJTF and Regional Economic Communities, particularly ECOWAS, to facilitate more coherent cross-border responses and address the transnational nature of the threats posed by Boko Haram and the ISWAP. The PSC may also task the AU Commission and the LCBC to undertake an assessment of the impact of the withdrawal of Niger from the MNJTF and develop strategy for mitigating adverse impacts.

PSC shaping a new maritime security architecture in the Gulf of Guinea

PSC shaping a new maritime security architecture in the Gulf of Guinea

Date | 5 June 2025

Tefesehet Hailu

Researcher, Amani Africa

On 23 April, the PSC held its 1275th session to discuss the imperatives of the Combined Maritime Task Force in addressing piracy in the Gulf of Guinea. The outcome of the meeting was adopted as a communiqué.

The session included a series of presentations and statements from key regional and continental stakeholders. However, despite the importance of receiving an update from the AU Political Affairs, Peace and Security Department, the department was not represented and therefore did not provide a briefing on the implementation of previous decisions.

One of the key outcomes of the session was the PSC’s endorsement of the Combined Maritime Task Force (CMTF) for the Gulf of Guinea as a standing, ready-to-deploy force, capable of delivering rapid and coordinated maritime security responses across the region. In addition to endorsing the CMTF, the PSC also affirmed the CMTF’s vision of a united, secure, safe, and resilient region, free from transnational organised crime.

Beyond expressing its endorsement, in an effort to set up the institutional backbone of the Task Force, the PSC requested the AU Commission to facilitate the further development of the Task Force, welcomed the adoption of the Concept of Operations (CONOPS) by additional member states, and encouraged others to consider joining the initiative. The Council also emphasised the need to advance the Task Force’s operational instruments and urged Member States of the Gulf of Guinea Commission to extend their political backing for its effective operationalisation. Furthermore, the PSC emphasised the need for the Military Staff Committee to visit the CMTF headquarters in Lagos to gather direct insights and advise the PSC on advancing its operationalisation. While this political commitment provides essential legitimacy and momentum, it must be accompanied by concrete resource mobilisation and inclusive engagement, ensuring that less-resourced littoral states are not left behind in the implementation process. Additionally, translating these institutional arrangements into a tangible maritime presence and effectiveness will require adequate funding, logistical support and coordination.

The outcome also reflects a growing momentum in developing institutional and operational frameworks for advancing maritime security in the Gulf of Guinea, deserving of sustained support from the AU. Additionally, symbolic steps, like the proposed flag-off ceremony and Nigeria’s readiness to host the CMTF headquarters, highlight political will on both sides of the AU and Member States. Institutionally, the PSC retreated its call for the AU Commission to take concrete measures to ensure inclusive stakeholder engagement, including the formal inauguration of the Committee of African Heads of Navies and Coast Guards (CHANS), as outlined in the AIMS 2050 framework.

The emphasis on coordinated maritime deployments and readiness to establish permanent headquarters suggests growing interest and commitment. However, the reliance on individual states for leadership and hosting functions, in the absence of a clear burden-sharing framework, also raises concerns about long-term sustainability and inclusivity.

On capacity building, the Council recognised the importance of intelligence sharing, joint operations, and strategic partners to support the Gulf of Guinea Commission in planning and conducting the AMANI Africa III Command Post Maritime Exercise. It rightly emphasised the need for tailored support—logistical, financial, and technical—for coastal Member States, and encouraged international partnerships for sustainable capacity development.

Concerning coordination and interoperability, the Council’s call for harmonising efforts between the CMTF and the Yaoundé Architecture reflects an increasing awareness of the fragmentation across regional efforts. Again, operationalising such structures will require not just institutional mandates but clarity on the division of labour among AU organs, RECs/RMs, and regional mechanisms.

Importantly, the emphasis on addressing the root causes of maritime crime, such as poverty, weak governance, and limited economic alternatives, signals a welcome and necessary shift toward a more holistic and preventive approach to maritime security. This broader perspective acknowledges that sustainable security cannot be achieved solely through military and law enforcement responses, but must also tackle the socio-economic and structural drivers that make maritime crime attractive or viable in coastal territories. By focusing on development deficits, corruption, youth unemployment, and lack of livelihoods, the approach has the potential to generate long-term stability and resilience in coastal communities. But without concrete interventions to address these conditions, the reference to dealing with root causes will remain hollow.

The inclusion of environmental protection discussions and the call for strategic environmental assessments (SEAs) to safeguard marine ecosystems marks a significant and commendable departure from earlier sessions where such concerns were often overlooked. This shift reflects a recognition of the interlinkages between maritime security and environmental sustainability, particularly as climate change, pollution, and unsustainable exploitation of marine resources increasingly contribute to insecurity in coastal regions. However, there is a need for clarifying the practical implications of conducting SEAs and the institutional and policy framework for anchoring such an exercise and the follow-up to it. Without defined implementation mechanisms and integration into existing regional frameworks, such as the African Blue Economy Strategy and 2050 AIMs, the commitment risks becoming a token gesture.

Lastly, although the meeting primarily focused on maritime security in the Gulf of Guinea, the PSC demonstrated a broader continental outlook by urging Member States to actively support the operationalisation of the Maritime Coordination Centre. This move is aimed at enhancing the coordination and governance of maritime safety and security across all five regions of the continent, reflecting the Council’s growing recognition of the interconnected nature of Africa’s maritime security challenges. Furthermore, the PSC acknowledged the Indian Ocean Commission’s participation in Gulf of Guinea Commission meetings and called for a consultative engagement with the Commission, signalling an effort to bridge regional maritime security efforts.

In the absence of updates from the Department of PAPS on the implementation of its previous decisions, the PSC reiterated its September 2023 decision, adopted during its 1174th session. The Council renewed its request for the Commission to expedite the establishment and operationalisation of a Coordination Mechanism—or Maritime Security Unit—within the AU Commission.

The content of this article does not represent the views of Amani Africa and reflect only the personal views of the authors who contribute to ‘Ideas Indaba’

Briefing on the synergy between the Global Framework Ammunition (GFA) Management and the Regional Arms and Ammunition Control Instruments

Briefing on the synergy between the Global Framework Ammunition (GFA) Management and the Regional Arms and Ammunition Control Instruments

Date | 3 June 2025

Tomorrow (4 June), the African Union (AU) Peace and Security Council (PSC) is scheduled to convene its 1281st meeting for a briefing on the synergy between the Global Framework Ammunition (GFA) Management and the Regional Arms and Ammunition Control Instruments.

Following opening remarks by Ambassador Innocent Shiyo, Permanent Representative of Tanzania to the AU and Chairperson of the PSC for June, Bankole Adeoye, AU Commissioner for Political Affairs, Peace and Security (PAPS), is expected to deliver a statement. Eric Kayiranga, Weapon and Ammunition Senior Advisor representing the Regional Centre on Small Arms (RECSA) in the Great Lakes Region, is also expected to make a presentation, followed by statements from representatives of the RECs/RMs. A representative of the UN is also expected to make a statement during the session.

This meeting is convened to explore the synergies and implementation of regional instruments on Small Arms and Light Weapons (SALW) adopted by AU Member States, alongside the Global Framework for Through-life Conventional Ammunition Management (GFA), in alignment with the Common African Defence and Security Policy (CADSP). It is worth recalling that the CADSP is a strategic framework adopted by Member States to promote a shared understanding of security needs, common defence and security threats and the necessity for collective action to address these challenges. It serves as a vital tool for AU Member States to coordinate their defence and security initiatives, advancing continental stability in alignment with Africa’s Agenda 2063 for sustainable development and peace. Furthermore, the AU Master Roadmap of Practical Steps to Silence the Guns in Africa by 2030 emphasises the importance of addressing the illicit proliferation and circulation of arms, with a specific focus on controlling the flow of ammunition into conflict zones. The GFA, on the other hand, serves as a comprehensive political framework encompassing fifteen objectives and eighty-five measures designed to prevent the diversion, illicit trafficking, and misuse of conventional ammunition. It also seeks to mitigate the risks of unplanned explosions and promote the safe and secure management of ammunition across its entire lifecycle, from production to final disposal. The framework addresses a broad spectrum of ammunition, including both small-calibre and large conventional types. Of particular relevance to Africa, the GFA aligns with the continent’s pressing peace and security challenges, especially the widespread proliferation of SALW and their associated ammunition. This proliferation significantly contributes to the escalation of armed conflict, terrorism, and transnational organised crime across the region.

Regional arms and ammunition control instruments, on the other hand, are critical frameworks, agreements and protocols established by regional organisations to regulate the production, transfer, storage and use of conventional arms, including SALW and their ammunition. These instruments are designed to address the pressing challenges of illicit proliferation, trafficking and misuse, which often fuel armed conflict, violence and regional instability. Their primary objectives include preventing unauthorised manufacturing, trafficking and diversion of arms and ammunition, enhancing security by reducing armed violence, terrorism and conflict through improved stockpile management and promoting regional collaboration, information-sharing and joint action to tackle cross-border challenges. On the continent, several key instruments exemplify these efforts. The ECOWAS Convention on SALW, their Ammunition and other Related Materials, adopted in 2006, is a legally binding agreement that replaced a 1998 moratorium. It focuses on controlling SALW, ammunition and related materials through transfer controls, stockpile management and tracing, while encouraging Member States to ratify the Arms Trade Treaty (ATT). The Nairobi Protocol for the Prevention, Control and Reduction of SALW, established in 2004, on the other hand, targets the Great Lakes Region, the Horn of Africa and bordering states. Coordinated by the RECSA, it mandates training, destruction of surplus firearms and cross-border cooperation to curb trafficking. The Central African Convention/Kinshasa Convention, adopted in 2010 by ECCAS, is legally binding and entered into force in 2017, covering SALW, ammunition and components for manufacture, repair and assembly, with a broader scope than other regional protocols.

At the continental level, there are no legally binding continent-wide instruments, but there are frameworks. The Bamako Declaration of 2000, a political Africa-wide instrument, establishes a common African position on illicit SALW proliferation, circulation and trafficking, strengthening regional and international cooperation. The AU is also guided by the AU Strategy on the Control of Illicit Proliferation, Circulation and Trafficking of SALW. The AU Commission also embarked on a process of coordination and alignment of the implementation of the GFA. A study titled ‘Synergies Between African Regional Instruments and Global Framework for Through-life Conventional Ammunition Management’ was conducted. This analysis explored the alignment between the four key African regional instruments highlighted above and the fifteen objectives of the GFA. Following a workshop held on 6 and 7 May 2025 in the AU Commission, gathering experts from RECs/RMs and RECSA, the zero-draft report of the study sets the stage for dialogue, reflection and a unified path forward.

Beyond mere assessment, the study illuminated gaps in the framework and proposed thoughtful areas for improvement, aiming to strengthen the execution of both regional instruments and the GFA itself. In terms of alignment and differences, it was noted that African regional instruments, with the exception of the Bamako Declaration, hold legal force, obligating their signatories, while the GFA operates on a voluntary basis, its guidelines backed only by political commitment, just like the Bamako Declaration. Additionally, the GFA addresses all types of conventional ammunition, from small-calibre rounds to artillery shells, whereas regional instruments limit their scope to ammunition for SALW. Consequently, the study’s comparison and analysis account for the binding legal responsibilities of State Parties to the regional instruments, but focus exclusively on SALW ammunition. At the same time, the GFA’s prioritisation of international cooperation and technical assistance, facilitated through mechanisms such as the United Nations SaferGuard Programme and the Ammunition Management Advisory Team (AMAT), presents valuable opportunities for supporting AU Member States and RECs in strengthening stockpile security.

Tomorrow’s session will therefore provide an opportunity for the PSC to engage in a focused discussion on the challenges associated with aligning and coordinating the GFA with existing regional arms control instruments, as emerged from the aforementioned study. In terms of challenges, one major concern is the limited financial and technical capacity of many Member States, which may be further strained by the introduction of new frameworks such as the GFA. Council may also consider the imperative of updating regional instruments to incorporate standards like the International Ammunition Technical Guidelines (IATGs), enhance risk reduction, improve inventory and tracing systems and strengthen gender mainstreaming and stakeholder cooperation.

Although the establishment of such legal frameworks at sub-regional levels helps respond to challenges specific to those regions and is a positive step, it has resulted in parallel legal regimes and has made responses fragmented. Even in regions that have instruments, implementation is still lacking. The fragmented response has also left regions such as the Sahel without an established instrument. As such, the PSC may follow up on the outcome of its 1085th meeting. First, it called for the integration of arms control and Weapons and Ammunition Management (WAM) programmes into the broader framework of Africa’s peace, security, and sustainable development agenda. Second, the Council requested the elaboration of a continental strategy to combat the proliferation of illicit firearms, including emerging categories of weaponry.

The Council may use this session to brainstorm on practical and sustainable measures to effectively bolster arms control and promote peace across the continent, drawing on the GFA. It is recalled that the 860th PSC session previously highlighted the persistent lack of reliable data on national stockpiles as a critical challenge. In response, the GFA’s call for transparency and systematic information-sharing—such as through the UN Register of Conventional Arms—can serve to enhance regional monitoring and auditing practices. Moreover, the PSC may revisit the conclusions of its 776th session, which drew a direct connection between illicit arms flows and broader threats such as transnational organised crime and terrorism. In this light, the GFA’s holistic and lifecycle-based approach to ammunition management offers a valuable framework for advancing regional strategies that address these underlying security drivers, while simultaneously aligning with the objectives of Sustainable Development Goal 16.4, which seeks to significantly reduce illicit arms flows.

It is also worth noting that tomorrow’s meeting is also being convened just few weeks before the convening of the preparatory meeting of States on the ‘Global Framework for Through-life Conventional Ammunition Management’ which will be held from 23 to 27 June 2025 at the UN Headquarters, as communicated by the UNODA in January 2025. A meeting expected to ‘explore possible options for the development of the process to ‘prevent diversion, illicit trafficking and misuse of ammunition; mitigate and prevent unplanned explosions at munition sites; ensure the safety and security of conventional ammunition throughout its life-cycle from the point of manufacture; and contribute to lasting peace, security and sustainable development.’

The expected outcome of the session is a communiqué. The PSC may express deep concern over the growing illicit flow of SALW in Africa. The PSC is also likely to reiterate the imperative of Member States and RECs/RMs to scale up efforts towards the full implementation of the regional SALW instruments. The PSC may underscore the operational role of RECs and the RECSA in supporting the implementation of regional arms control instruments and advancing alignment between these instruments and the GFA. The PSC may also call for the establishment of systematic stockpile audits, improved coordination among regional mechanisms and the development of specialised training programmes. The Council may, in particular, propose the establishment of regional training initiatives grounded in the regional instruments, the AU frameworks and the IATG and the International Small Arms Control Standards (ISACS), in order to build capacity for effective weapons and ammunition management. The Council may call for leveraging the GFA’s provisions on export controls and risk assessments related to diversion to mitigate external illicit arms transfers, which remain a persistent threat to peace and security across the continent. PSC could urge the AU Commission, Member States, and RECs/RMs to engage in the preparatory meeting at the UN Headquarters in New York, scheduled for 23 to 27 June 2025, by sharing valuable experiences and best practices on the safe and secure through-life management of ammunition. The Council may also encourage Member States to use the key findings and recommendations from the study conducted by the Commission in close collaboration with the four regions as a reference in making their interventions during the preparatory meeting. The PSC may encourage Member States to integrate the objectives of the GFA into national and SALW strategies, in alignment with the AU Master Roadmap for Silencing the Guns by 2030. The Council may request technical assistance from the UNODA, the AMAT, and the UNREC to support national authorities in implementing regional and continental instruments on marking, tracing, and stockpile management, based on the IATG and the ISACS. The PSC may request the AU Commission, in collaboration with RECs, to develop a comprehensive monitoring and evaluation framework to track progress in GFA implementation, emphasising evidence-based interventions and sustained institutional coordination. The PSC may also reiterate its request from its 1085th session and call on the AU Commission to follow up and report to the Council.

AU expresses deep concern as Africa faces growing challenges for mine action

AU expresses deep concern as Africa faces growing challenges for mine action

Date | 2 June 2025

The African Union (AU) Peace and Security Council’s (PSC) 1271st session, on 1 April, dedicated to the International Day for Mine Awareness and Assistance in Mine Action, highlighted growing challenges for mine action in Africa. The session served as an occasion to review the state of affairs around anti-personnel landmines, Explosive Remnants of War (ERW) and Improvised Explosive Devices (IEDs) on the continent as well as to highlight the threats posed by Explosive Weapons in Populated Areas (EWIPA). A communiqué was adopted as the outcome of the session.

2025 marks the final year to meet the deadline set by the 1997 Anti-Personnel Mine Ban Convention (Ottawa Convention) and the 2014 Declaration of State Parties to the Convention and the Prohibition of Anti-Personnel Mines (Maputo Declaration) for a mine-free world, now extended to 2029 following the 5th Review Conference in Siem Reap, Cambodia last year. According to the latest 2024 Landmines Monitor Report, offering a comprehensive global overview of developments in mine ban and action since 1999, as of October 2024, 33 States Parties have yet to fulfil their mine clearance obligations under Article 5. Of these 14 are AU Member States: Angola, Chad, the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Eritrea, Ethiopia, Guinea-Bissau, Mauritania, Niger, Nigeria, Senegal, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan, and Zimbabwe.

This session came against the background of global setbacks facing the Ottawa Convention, including the use of anti-personnel landmines in some conflicts and the announcement by some European countries of a plan of withdrawal, citing the deteriorating security situation in the region, marked by military threats to States bordering Russia and Belarus. At the continental level, the re-emergence of landmines in some countries previously declared mine-free—including Nigeria, Guinea-Bissau, and Mauritania—has raised alarm. Mozambique, which was declared mine-free in 2015, also faces renewed threats due to the use of improvised mines by insurgents in the Cabo Delgado province. Ethiopia also reported massive antipersonnel landmine contamination in 2023, with over 100 km² affected, while Angola, Chad, Eritrea, and Mauritania reported contamination levels ranging from 20 to 99 km².

As one of the regions of the world affected by landmines and increasingly by the use of Explosive Weapons in Populated Areas, the issues highlighted in this session are of significance for the safety and well-being of civilians on the continent. The human toll of landmines and explosive remnants of war (ERW) remains high. In 2023, at least 5,757 casualties were recorded globally, with civilians bearing the brunt of the impact. Nigeria, Burkina Faso, Mali, and Ethiopia were among the ten countries with the highest casualty rates, pursuant to the Landmines Monitor Report.

In view of the foregoing, the PSC expressed deep concern over the persistent threat posed by anti-personnel mines, ERW and the growing danger of IEDs, which have become the weapon of choice for non-state armed groups, including terrorist organisations, across the continent.

Funding was one of the critical issues with respect to which the PSC voiced deep concern. It noted that dwindling financial support for Mine Action severely hampers demining efforts in Member States affected by landmines and ERW. This funding shortfall is compelling nations to significantly scale back their Land Mine Action Programmes and clearance operations. There are concerns that shifts in policy and funding priorities of major funding countries, notably the U.S., could have severe repercussions for demining efforts in more than 14 AU Member States reported to be contaminated by landmines. At the same time, despite the increase in international funding for mine action, which surpassed $1 billion in 2023, no African country was among the top ten recipients of international support. Ukraine alone received $308 million—39% of all international donor funds—while African countries, including Chad, Ethiopia, Mauritania, Niger, Nigeria, and Senegal, received a combined total of just $19 million over five years (2019–2023), representing less than 1% of global mine action funding.

In addition to a general appeal to the international partners to increase support for Africa’s efforts to eradicate landmines and ERW, the PSC focused on two other supplementary measures. First was the need for national ownership and the primary responsibility of states, including in mobilising resources for mine action. Second, and notably, it called for ‘the establishment of a continental mechanism for mine action.’ What is missing in this respect is how to source and mobilise the requisite funds for supporting member states and for the continental mechanism to play the role of filling in the growing gaps in mine action.

This year’s session additionally put a spotlight on the issue of the use of Explosive Weapons in Populated Areas (EWIPA), in light of the increasing urbanisation of armed conflicts and the use of explosive weapons, as recently observed in Sudan and the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). The use of such weapons in populated areas has been documented to have devastating impacts on civilians and civilian infrastructure.

Instead of mobilising political commitment for ending the use of explosive weapons in populated areas, the PSC resorted to a less ambitious policy position. It thus encouraged member states to urgently review and adapt their military policies and practices, and to adopt policy measures that limit the use of explosive weapons with wide-area effects in populated areas—unless adequate mitigation measures are in place to reduce their broad impact and the risk of civilian harm.’ It was a missed opportunity that the use of the words ‘encourage’ and ‘limit’ watered down the force of the policy course of action to be adopted by member states. Not only are member states encouraged only to ‘limit’, but also such limitation can be put aside if ‘adequate mitigation measures’ for reducing the broad impact of the use of explosive weapons are taken. Despite the significance of the formulation of the PSC’s request as a negotiated compromise, the qualifications can additionally undermine effective implementation.

Regarding the Political Declaration on Strengthening the Protection of Civilians from the Humanitarian Consequences Arising from the Use of Explosive Weapons in Populated Areas—formally endorsed by 83 states in November 2022—the PSC requested the AU Commission to continue sensitising Member States on the humanitarian impacts of such weapons and the importance of the Declaration. The PSC also urged those Member States that have not yet done so to endorse the Declaration, given that only 11 AU Member States have done so to date. In view of the upcoming Second International Conference on the Political Declaration, scheduled for November 2025 in Costa Rica, the PSC encouraged AU Member States to actively participate in preparations, including through the drafting of a Common Plan of Action outlining steps in support of the Declaration.

Despite these growing challenges, the policy response and review by the AU shows no progress. Accordingly, in terms of the PSC’s long-standing request for the review of the AU Mine Action and Explosive Remnants of War Strategic Framework (2014–2017) and the development of a Counter-Improvised Explosive Devices (C-IED) Strategy, the session underscored the urgent need for the AU Commission to share the draft of these documents with Member States for review and validation. Although Regional Economic Communities (RECs) are not explicitly mentioned in this context, their engagement in the review and validation process will be important before their submission to the Council for consideration.

The content of this article does not represent the views of Amani Africa and reflect only the personal views of the authors who contribute to ‘Ideas Indaba’

Provisional Programme of Work of the Peace and Security Council for June 2025

Provisional Programme of Work of the Peace and Security Council for June 2025

Date | June 2025

In June 2025, the United Republic of Tanzania assumes the role of chairing the African Union (AU) Peace and Security Council (PSC). The Council’s Provisional Programme of Work for the month envisages six substantive sessions. Of these, three are dedicated to thematic issues, while the remaining three will address conflict/region-specific issues. All sessions are expected to be at an ambassadorial level.

The first session of the month, scheduled for 4 June, will feature a briefing on the synergies between the Global Framework for Through-life Conventional Ammunition Management and existing regional arms and ammunition control instruments. Adopted by the United Nations General Assembly in December 2023 through Resolution 78/47, the framework complements key continental agreements, such as the Nairobi Protocol, the ECOWAS Convention, and the Kinshasa Convention. Previous PSC communiqués, notably the 788th session in August 2018, convened in preparation for Africa Amnesty Month and the 1029th session marking the 2021 commemoration, have emphasised the need to align the framework’s objectives with regional mechanisms. This alignment is essential to effectively address the continued illicit proliferation, diversion, and misuse of small arms and light weapons (SALW) and ammunition, which remain key drivers of conflict, terrorism, and violent extremism across the continent. A critical focus for the session is expected to be the need to enhance national and regional capacities for stockpile management. As previously highlighted during the 14 March 2019 briefing on SALW proliferation, this requires harmonising the framework’s focus on safety, security, and sustainability with regional initiatives in order to prevent unplanned explosions and the diversion of weapons to unauthorised actors. The session is also expected to explore how to better integrate gender mainstreaming into regional arms control strategies, in accordance with Objective 14 of the framework.

On 10 June, the second session will focus on an update regarding the activities of the Multinational Joint Task Force (MNJTF) and a review of the Regional Strategy for the Stabilisation, Recovery, and Resilience (RSS) of Boko Haram-affected areas in the Lake Chad Basin (RS-SRR) of the Lake Chad Basin. The last time the PSC discussed the MNJTF was during its 1254th session in January 2025, where it renewed the Force’s mandate for an additional 12 months. Furthermore, it urged the LCBC to step up diplomatic engagement with Niger to ensure its full reintegration into the MNJTF, while advocating for a comprehensive, inclusive, and multi-sectoral approach to stabilisation—particularly through strengthened civil-military cooperation to enable the return of displaced communities. The PSC also requested regular progress updates from the AU Commission and the LCBC Secretariat to maintain oversight and ensure accountability. Apart from following up on these issues and the review of the security and operational situation of the MNJTF, the session is expected to receive an update on the revised regional stabilisation strategy. It is to be recalled that on 20 September 2024, the 5th meeting of the Steering Committee for the implementation of this regional strategy took place virtually. The meeting approved the adjusted Regional Strategy and Community-based Reconciliation and Reintegration Policy for 2025-2030.

The PSC is expected to convene its third substantive session on 12 June, dedicated to an update on the Situation in South Sudan, marking the third time it has convened on the matter since the outbreak of violence triggered by the 4 March attack on the South Sudan People’s Defence Force base in Nasir. The political and security environment in South Sudan is notably deteriorating, further compounded by the arrest and continued detention of First Vice President Dr. Riek Machar Teny on 26 March 2025 in Juba. This upcoming session is expected to build on key decisions and challenges highlighted in PSC’s Press Statement that was adopted by the 1270th meeting held on 31 March 2025 and the communiqué of the 1265th meeting, held on 18 March 2025. In its Press Statement adopted at the 1270th session, the PSC urged the AU Commission Chairperson to urgently deploy a high-level delegation to South Sudan, led by the Panel of the Wise, and called on the C5 to enhance its engagement with all actors in support of AU and IGAD efforts toward lasting peace and stability. In response, the Chairperson, Mahmoud Youssouf Ali, promptly deployed a high-level delegation from the Panel of the Wise to Juba to help ease tensions and encourage dialogue. In addition to the deployment of the Panel of the Wise, the Chairperson of the AU Commission conducted an official visit to Juba, in coordination with the IGAD, from 5 to 6 May 2025 to engage South Sudanese leadership on the evolving political and security landscape. During the visit, the Chairperson held high-level talks with President Salva Kiir Mayardit and senior officials, focusing on protecting the gains of the Revitalised Agreement on the Resolution of the Conflict in South Sudan, advancing inclusive national dialogue, ensuring the credible and timely implementation of the transitional roadmap, and strengthening governance institutions. The upcoming session is expected to revisit these priorities in line with ongoing efforts by regional and continental actors, including the AU High-Level Ad Hoc Committee on South Sudan (C5). It is also expected that the PSC will consider the report of the Panel of the Wise.

On 17 June, the PSC will hold its fourth session, which will focus on a briefing on the status of the implementation of the Common African Defence and Security Policy (CADSP) and other relevant AU instruments related to continental defence and security. This session is being held in line with the 1159th PSC communique that requested the AU Commission Chairperson to regularly brief the PSC on the status of the implementation of the policy and other relevant AU instruments on defence and security on the Continent. Although the CADSP has been in existence for two decades, it only received focused attention from the PSC for the first time during its 1159th session held on 22 June 2023. That session included a briefing not only on the CADSP’s implementation but also on the operationalisation of the African Standby Force (ASF). During the discussion, the CADSP was underscored as the ‘bedrock of Africa’s collective defence and security,’ and the PSC stressed the urgent need to reinvigorate and operationalise all pillars of the continental peace and security architecture, including the ASF. The CADSP, which complements the AU Peace and Security Protocol, sets out objectives, principles and frameworks aimed at advancing a collective security approach for the continent. Gaps in the implementation of key CADSP pillars, including conflict prevention, peacebuilding, and the integration of regional defence mechanisms, as well as foreign military activities on the continent, remain unattained. Therefore, this upcoming session presents an opportunity to assess progress, identify gaps, and reaffirm commitments in the implementation of CADSP.

The PSC will have consultations with the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights (ACHPR) on 19 June. The consultative meeting is being held in accordance with Article 19 of the PSC Protocol, which envisions close collaboration between the PSC and the ACHPR in the promotion of peace, security, and stability across the continent. In addition to the provision of the Protocol, during the 866th session, the PSC, as a means to enhance and institutionalise its collaboration with the ACHPR, decided to hold annual joint consultative meetings between the two organs. The last such consultation took place in August 2021. During that 1019th session, the communique on the consultation, among others, underscored ‘the importance of mainstreaming human rights throughout conflict prevention, management, stabilisation, resolution to post-conflict reconstruction and development.’ Despite the absence of formal consultations in recent years, the PSC has continued to adopt decisions relevant to the ACHPR’s mandate. Notably, during its 1213th session in May 2024, the PSC requested the ACHPR for an investigation into the human rights situation in El Fasher and other areas of Darfur, and requested a report with recommendations to ensure accountability for perpetrators. As such, an update on the status and progress of this investigation is expected to feature in the upcoming discussions. The discussion will likely address pressing concerns such as impunity, gender-based violence, and widespread human rights violations in conflict-affected regions, including the DRC, South Sudan, Sudan, and the Sahel. The PSC is also anticipated to engage with ACHPR reports on abuses linked to terrorism and unconstitutional changes of government, and may urge Member States to implement key instruments such as ACHPR Resolution 448 (2020), which outlines the human rights dimensions of conflict situations. Further emphasis may be placed on enhancing early warning systems through closer collaboration with ACHPR’s monitoring and reporting frameworks.

The last session for the month, which is scheduled for 25 June, will focus on providing an update on ‘the implementation of the PSC and EAC/SADC decisions on the situation in Eastern Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC).’ Since the beginning of the year, the conflict in the DRC has intensified as a result of the renewed violence involving the Mouvement du 23 Mars (M23) rebel group, its seizure of Goma, and mounting diplomatic tensions between the DRC and Rwanda. In response to the deteriorating situation, the PSC, EAC and SADC have undertaken diplomatic efforts resulting in several key decisions. Among these is the Communique issued at the Joint EAC and SADC Summit of Heads of State and Government held on 8 February 2025 in Dar es Salaam, which called for an immediate ceasefire, the withdrawal of foreign forces, and the merger of the Luanda and Nairobi Processes. It also proposed the inclusion of additional facilitators to enhance the peace process and urged the resumption of direct dialogue with all armed groups, including M23, under the unified framework. The PSC, for its part, convened the 1256th emergency ministerial session on 28 January 2025 and its 1261st session on 14 February 2025. During the 1261st session, the Council endorsed the outcomes of the Joint EAC-SADC Summit of 8 February 2024, the Extraordinary SADC Summit of 31 January 2025, and the 24th Extraordinary EAC Summit of 29 January 2025—each of which addressed the worsening crisis in eastern DRC. To further strengthen coordination, the PSC also decided to establish a Joint AU/EAC/SADC Coordination Mechanism to provide technical support, foster collaboration with other Regional Economic Communities and mechanisms and ensure the harmonisation of implementation of peace initiatives. Subsequently, during the 2nd Joint EAC-SADC Summit of Heads of State and Government held on 24 March 2025, the joint summit appointed the facilitators of the merged Luanda-Nairobi peace process, which is composed of five former Presidents. On the other side, the AU designated the President of Togo, Faure Gnassingbé, as the AU Mediator, taking over from the President of Angola. Apart from the convening in Lome, Togo, of the Mediator and the EAC-SADC Facilitators on 17 May, the US launched talks between Rwanda and DRC as well. It is anticipated that the session will take stock of the conflict situation and the state of peace efforts both within the AU, EAC-SADC frameworks and the alignment of other initiatives with the regional efforts. Furthermore, given the situation that has been further exacerbated by a deepening humanitarian crisis marked by mass displacement and increasing incidents of sexual and gender-based violence, which underscores the critical need for unimpeded humanitarian access, it is expected that the session will discuss mechanisms for a coordinated response.

The PSC Committee of Sanctions is also scheduled to meet on 24 June to provide updates on the activities of the Committee.

Monthly Digest on The African Union Peace And Security Council - April 2025

Monthly Digest on The African Union Peace And Security Council - April 2025

Date | April 2025

In April, under the stand-in chairship of the Republic of Uganda, the African Union (AU) Peace and Security Council (PSC) had a Provisional Programme of Work (PPoW) which anticipated six substantive sessions and the PSC’s 4th Annual Joint Retreat with the African Peer Review Mechanism (APRM).