Consideration of the half-year report of the Chairperson of the AU Commission on elections in Africa

Consideration of the half-year report of the Chairperson of the AU Commission on elections in Africa

Date | 25 January 2026

Tomorrow (26 January), the African Union (AU) Peace and Security Council (PSC) will convene its 1327th Session to consider the mid-year report of the Chairperson of the AU Commission on elections in Africa, covering the period between July and December 2025.

Following the opening statement of the Chairperson of the PSC for the month, Jean-Léon Ngandu Ilunga, Permanent Representative of the Democratic Republic of Congo to the AU, Bankole Adeoye, the Commissioner for Political Affairs, Peace and Security (PAPS), is expected to present the report. Statements are also expected from the representatives of Member States that organised elections during the reporting period.

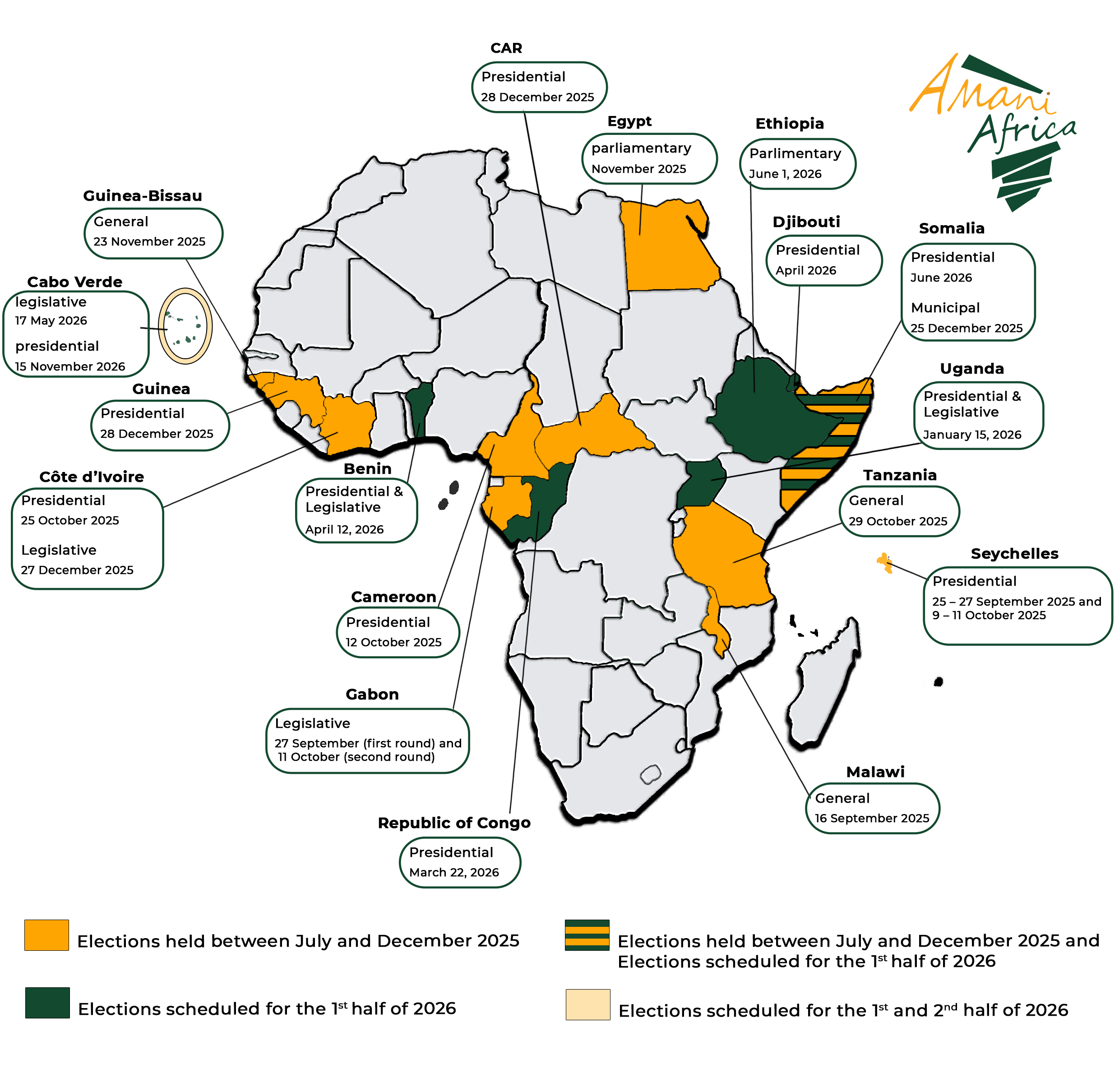

As per the PSC’s decision from its 424th session in March 2014, which mandates periodic updates on African electoral developments, the Chairperson presents a mid-year elections report. The previous update was delivered during the 1288th PSC session on 4 July, 2025 and covered electoral activities from January to June 2025. Tomorrow’s briefing will similarly provide accounts of elections conducted from July to December 2025, covering elections held in Cameroon, the Central African Republic, Côte d’Ivoire, Egypt, Gabon, Guinea-Bissau, Guinea, Malawi, the Seychelles, Somalia, and Tanzania, while also outlining the electoral calendar for the first half of 2026.

Across the second half of 2025, governance trends across Africa reflected a complex and often uneven interplay between electoral continuity, democratic backsliding, and institutional resilience. A recurring pattern was the consolidation of executive power through elections held in constrained political environments, frequently following constitutional changes that weakened term limits or enabled incumbents or transitional authorities to entrench themselves. Many of these polls were marked by low or moderate voter turnout, opposition boycotts or exclusions, and contested credibility, even where regional and continental observation missions officially endorsed peaceful conduct, highlighting a growing gap between formal electoral procedures and substantive democratic competition. At the same time, episodes of acute instability, most notably the military interruption of elections in Guinea-Bissau, underscored the continued fragility of civilian rule in some contexts, prompting robust but reactive responses from regional bodies. In contrast, a smaller number of cases demonstrated democratic resilience through competitive elections, peaceful concessions, and credible alternation of power.

In the aftermath of Cameroon’s contested 12 October 2025 presidential election, President Paul Biya was re-elected to an eighth term amid heightened political tensions. Post-election protests were reported in parts of the country, with security forces intervening to restore order, resulting in casualties. The Constitutional Council confirmed Biya’s victory with 53.7% of the vote, a result rejected by opposition candidate Issa Tchiroma Bakary, who claimed victory and accused authorities of systematic manipulation. The AU deployed an election observer mission led by Bernard Makuza, former Prime Minister and former President of the Senate of the Republic of Rwanda, composed of 40 short-term observers (STOs). Later, a joint statement from the AU and the Economic Community of Central African States (ECCAS)indicated that ‘the election was conducted peacefully, with respect for democratic values and citizen participation.’ They also noted low turnout and urged stakeholders to channel grievances through legal mechanisms.

In the Central African Republic’s 28 December 2025 presidential election, the incumbent President Faustin-Archange Touadéra secured a third term, garnering approximately 76.15 % of the vote according to provisional results from the National Elections Authority, which will be officially validated by the Constitutional Court. Touadéra’s victory follows a controversial 2023 constitutional referendum that abolished presidential term limits and extended term lengths, enabling him to run again and entrench his decade-long rule. The major opposition coalition boycotted the vote, decrying an unequal political environment and unfair conditions, and some challengers have alleged electoral malpractice and fraud. Voter turnout was at around 52%, reflecting mixed public engagement amid ongoing instability, even as the election technically proceeded peacefully and without widespread unrest reported.

The 2025 electoral cycle in Côte d’Ivoire opened with the presidential election on 25 October, followed by legislative polls on 27 December. According to the electoral commission, President Alassane Ouattara won decisively with 89.8% of the vote, while businessman Jean-Louis Billon trailed at 3.09%. Voter turnout stood at 50.1%, underscoring limited public participation. At the invitation of Ivorian authorities, the AU and the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) deployed a joint Election Observation Mission (EOM) of more than 250 observers across the country, reflecting strong regional engagement. Their preliminary report highlighted candidate exclusions, weak opposition presence, accessibility challenges, and logistical shortcomings. For the December legislative elections, the AU dispatched a separate mission of 31 observers to assess preparations, voting operations, and the post-election environment.

In Egypt, following the August senate elections, parliamentary elections were conducted in multiple phases starting in November, producing a legislature overwhelmingly aligned with President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi. His political bloc secured the super-majority required to advance constitutional amendments, consolidating executive dominance. Overall turnout and participation levels fluctuated.

The 23 November 2025 general elections in Guinea-Bissau, intended to produce a legitimate presidential and legislative outcome in a country long beset by political fragility, were abruptly upended when military forces seized power on 26 November, a day before provisional results were to be announced. Both incumbent President Umaro Sissoco Embaló and opposition candidate Fernando Dias da Costa had claimed victory prior to the official tally, but the military takeover involved storming the National Electoral Commission’s offices, the seizure and destruction of ballots, tally sheets and servers, and suspension of the entire electoral process, making completion of the vote effectively impossible. Major-General Horta Inta-A Na Man was installed as transitional president and appointed a new cabinet, drawing accusations from opposition figures and observers that the coup was either staged or exploited to forestall the constitutional transfer of power and preserve entrenched elite interests. In response, ECOWAS convened an extraordinary summit on 27 November, condemned the coup, suspended Guinea-Bissau, rejected any arrangements undermining the electoral process, and demanded the immediate declaration of the 23 November election results, while mandating a high-level mediation mission led by Sierra Leone’s President Julius Maada Bio. The PSC followed on 28 November by also suspending Guinea-Bissau, strongly condemning the coup, and calling for the completion of the electoral process and inauguration of the winner during its 1315th session. The Council also tasked the AU Commission Chairperson to create an inclusive AU Monitoring Mechanism, in collaboration with ECOWAS and stakeholders, to monitor the situation, especially the implementation of ECOWAS and PSC decisions.

In the 28 December 2025 presidential election in Guinea, held under a new constitution that followed the 2021 military coup, junta leader Mamady Doumbouya secured a landslide victory with 86.72 % of the vote and was later sworn in as president, marking the end of the formal transitional period since he seized power. AU observers were deployed to monitor the campaign and voting phases, with a mission arriving in mid-December and issuing preliminary statements that attested that the election took place in a peaceful, orderly, and credible environment. However, the electoral trajectory, notably a constitutional referendum earlier in 2025 that amended the legal framework to allow members of the ruling military authorities to stand as candidates, has deepened concerns about compliance with the African Charter on Democracy, Elections and Governance (ACDEG) Article 25(4), which seeks to restrict participation of those who have seized power through unconstitutional means.

In Malawi’s 16 September 2025 general elections, former President Peter Mutharika won a clear victory over incumbent President Lazarus Chakwera, securing 56.8 % of the vote to Chakwera’s 33%, with turnout around 76% of registered voters, prompting a peaceful concession by Chakwera and a commitment to a smooth transfer of power. The elections were observed by a joint African Union–COMESA Election Observation Mission and a SADC Electoral Observation Mission, both deployed at the invitation of Malawi’s government to assess compliance with national, regional, and international democratic standards, and to engage with key electoral stakeholders, including the Malawi Electoral Commission (MEC), political parties, civil society and media. Preliminary observation reports highlighted a generally peaceful and orderly process, with long queues and broad voter participation, though technical issues such as late polling station openings and structural challenges (e.g., biometric machine failures and the need for improved dispute resolution timelines) were noted, pointing to areas for future reform. This election reinforced Malawi’s democratic resilience and provided lessons for Africa on peaceful leadership alternation and the significance of robust electoral frameworks.

In the 2025 Seychelles general and presidential elections, the multi-stage process began with presidential and National Assembly polls on 25–27 September 2025, observed by a Joint AU and COMESA Election Observation Mission following an invitation from the Government and Electoral Commission; the mission engaged with key stakeholders across political, media, civic and institutional spheres to assess compliance with continental democratic standards enshrined in ACDEG and related instruments. According to the Joint Preliminary Report of the Joint mission, the candidate secured an outright majority in the first round, triggering a run-off held from 9 -11 October 2025 between opposition leader Patrick Herminie of the United Seychelles party and incumbent President Wavel Ramkalawan of Linyon Demokratik Seselwa. Herminie won the run-off with 52.7% of the vote to Ramkalawan’s 47.3%, returning his party to executive leadership and reversing the 2020 result that had first brought Ramkalawan to office. Observers and regional bodies, including SADC, noted the generally peaceful, orderly and professionally managed electoral environment.

In Gabon, the 27 September (first round) and 11 October (second round) parliamentary elections consolidated President Brice Oligui Nguema’s political dominance following his April presidential win, with his newly formed Democratic Union of Builders (UDB) securing a decisive majority in the National Assembly, winning around 101–102 out of 145 seats and relegating the long-dominant Gabonese Democratic Party (PDG) to a distant second, alongside a handful of smaller parties and independents. According to International IDEA’s Global State of Democracy Tracker, while the elections were largely peaceful and marked a significant shift in Gabon’s post-coup political landscape, they were also marred by irregularities, including missing ballots and annulments in several constituencies.

In Tanzania, the general elections held on 29 October 2025 produced an overwhelmingly one-sided result with President Samia Suluhu Hassan declared the winner on over 98% of the vote, but they were marred by deep controversy, violent unrest, and allegations of severe democratic deficits. The African Union Election Observation Mission’s preliminary report indicated that the elections “did not comply with AU principles, normative frameworks, and other international obligations and standards for democratic elections”, noting a restricted political environment, opposition boycotts and exclusions, internet shutdowns, outbreaks of deadly protests, and significant procedural irregularities that compromised electoral integrity and peaceful acceptance of results. On the other hand, the Chairperson of the African Union Commission, H.E. Mahmoud Ali Youssouf, issued a public statement congratulating President Suluhu on her victory while expressing regret at the loss of life in post-election protests and emphasising respect for human rights and the rule of law.

The period also marked a pivotal shift in Somalia’s electoral framework with the introduction of direct municipal elections. Somalia’s municipal elections held on 25 December 2025 in Mogadishu’s Banadir region introduced direct, one-person-one-vote polling for the first time in nearly six decades, a major departure from the indirect, clan-based model used since 1991 and direct voting last seen in 1969. The polls, involving some 1,604 candidates competing for 390 council seats and more than 500,000 registered voters, were widely framed by authorities and local observers as a critical first step toward restoring universal suffrage and laying the groundwork for nationwide direct elections scheduled for 2026, and showcased significant logistical and security efforts amid ongoing instability and insurgent threats. While the exercise proceeded under heightened security and with heavy public interest, it was also shadowed by political tensions, including opposition boycotts and concerns about inclusivity and turnout.

Furthermore, the report will highlight elections scheduled between January and June 2026. The majority of elections planned for 2026 will take place in the first half of the year, with Benin, Cape Verde, Djibouti, Ethiopia, Somalia, and Uganda holding polls during this period.

Uganda opened Africa’s 2026 election cycle with a presidential poll on 15 January. The presidential election saw long-time incumbent President Yoweri Museveni extend his rule into a seventh term, securing approximately 71.6 % of the vote against opposition leader Robert Kyagulanyi (Bobi Wine), who received about 24.7 %, in a contest marked by significant controversy and political tension. Official results indicated a 52.5 % voter turnout, the lowest since the return to multiparty politics. The joint preliminary statement of The African Union – Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa and the Inter-Governmental Authority on Development Election Observation Mission indicated that Uganda’s elections proved more peaceful than the 2021 election, earning praise for voter patience, professional staff, and transparent counting, though concerns persisted over military involvement, internet shutdowns, opposition arrests, media bias, high fees excluding marginalized groups, Electoral Commission independence issues, and Election Day delays.

The Republic of Congo is scheduled to hold its presidential election on 22 March 2026, with incumbent President Denis Sassou Nguesso officially nominated by the ruling Congolese Labour Party (PCT) to run for another term alongside candidates from opposition parties.

The 2026 presidential election in Djibouti is scheduled to take place by April 2026, with incumbent President Ismaïl Omar Guelleh, who has governed the country since 1999, formally nominated by the ruling Rassemblement Populaire pour le Progrès (RPP) to seek a sixth term following a constitutional amendment in late 2025 that removed the presidential age limit, allowing the 77-year-old leader to run again.

The 7th general election in Ethiopia is scheduled to be held on 1 June 2026, with the National Election Board of Ethiopia (NEBE) confirming the official election timetable, including candidate registration and campaigning periods ahead of polling day. A wide range of political parties are expected to contest seats in the House of Peoples’ Representatives, including the ruling Prosperity Party and several opposition and regional parties participating with their candidates across constituencies.

The national election process in Somalia is expected to take place in June 2026 under a newly adopted electoral framework aimed at moving toward universal suffrage and direct elections after decades of indirect, clan-based vote systems. Preparatory local polls and voter registration efforts were conducted in late 2025 as part of this transition, although there remains significant political disagreement over the roadmap and mechanisms for the upcoming national vote. Several political figures, including incumbent President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud and other declared or prospective contenders such as Abdi Farah Shirdon, are positioning themselves for the upcoming presidential race amid a fractured political landscape.

In Benin, President Patrice Talon steps down in line with constitutional term limits, breaking with the regional trend of incumbents extending their rule. The 2026 presidential election in Benin is set for 12 April 2026, with former finance minister Romuald Wadagni, endorsed by outgoing President Talon, emerging as a leading candidate after the ruling coalition cleared the required sponsorship thresholds. On 11 January 2026, parliamentary and local elections were held, in which the ruling Progressive Union for Renewal and the Republican Bloc together won all 109 seats in the National Assembly under a new 20 % threshold that left the main opposition without representation. These votes followed a failed coup attempt on 7 December 2025, when a small group of soldiers briefly announced the overthrow of the government but were quickly contained by loyal forces with regional support.

The Republic of Cabo Verde will hold its legislative elections on 17 May 2026 and its presidential election on 15 November 2026, with a possible second round for the presidency on 29 November if no candidate wins an outright majority. President José Maria Neves announced the dates after consultations with political parties and the National Elections Commission, and key parties preparing to contest include the ruling Movement for Democracy (MpD) and opposition parties such as the African Party for the Independence of Cape Verde (PAICV) and the Independent and Democratic Cape-Verdean Union (UCID).

The expected outcome is a communiqué. The PSC may take note of the Chairperson’s elections report, covering electoral developments from July to December 2025 and the electoral calendar for the first half of 2026. The PSC may commend Member States where elections were conducted peacefully and led to credible outcomes, while encouraging those facing post-electoral tensions or transitions to resolve disputes through constitutional and legal mechanisms. The Council may reiterate its condemnation of unconstitutional changes of government, and call for the restoration and completion of disrupted electoral processes in line with AU norms. It may further underscore the importance of aligning national electoral frameworks with the African Charter on Democracy, Elections and Governance, particularly concerning term limits, inclusivity, and the participation of transitional authorities. The PSC may encourage Member States to invite AU election observation missions in a timely manner, undertake necessary electoral and institutional reforms, ensure the neutrality of security forces, and uphold restraint and responsibility among all stakeholders to promote peaceful, credible, and inclusive elections across the continent.

Sudan’s Crisis is Africa’s Crisis - And Its Responsibility

Sudan’s Crisis is Africa’s Crisis - And Its Responsibility

Date | 22 January 2026

INTRODUCTION

Sudan is now the epicenter of one of the world’s deadliest conflicts and most desperate humanitarian crises. The numbers speak for themselves: since 2023, more than 150,000 people are estimated to have died as a result of violence and other related causes, 7.3 million have been newly internally displaced—on top of 2.3 million already displaced, bringing the total 9.6 million, 4.3 million have fled as refugees to neighboring countries, and more than 30 million people—two-thirds of the population—require humanitarian assistance (here). The atrocities committed defy words, and the battle for El-Fasher—its fall to the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) and the unbearable reports that followed—has revived the darkest echoes of an earlier tragedy: the scorched-earth campaign waged in Darfur following the 2003 armed rebellion in that region. The fear now is stark: what happened there could happen again, elsewhere.

Briefing on the situation in South Sudan

Briefing on the situation in South Sudan

Date | 22 January 2026

Tomorrow (23 January), the African Union (AU) Peace and Security Council (PSC) will convene a session to receive an update on the situation in South Sudan.

Following opening remarks from Jean Leon Ngandu Ilunga, the Permanent Representative of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) to the AU and chairperson of the PSC for the month of November, Bankole Adeoye, the AU Commissioner for Political Affairs, Peace and Security, is expected to make a statement. South Sudan, as a country concerned, is also expected to make a statement. Others expected to make statement include the Inter-Governmental Authority on Development (IGAD), as the concerned regional economic community/Mechanism (REC/M), South Africa (as Chairperson of the AU Ad Hoc High-Level Committee on South Sudan (C5), Chairperson of the Reconstituted Joint Monitoring and Evaluation Commission (R-JMEC); and the representative of the United Nations Secretary-General and Head of the United Nations Mission in South Sudan (UNMISS).

The political, security, and humanitarian situation in the country appears to have deteriorated further since the Council last discussed South Sudan on 28 October 2025. Political tension is mounting. Fighting and insecurity are spreading.

It is to be recalled that in its communiqué adopted at the last session of its 1308th meeting held on 28 October, the AU Peace and Security Council (AUPSC) underscored the need to avoid any actions that could jeopardise the full implementation of R-ARCSS, which it described as the only viable pathway towards a consensual and sustainable solution to the country’s challenges.

However, R-ARCSS is now on the verge of collapse. The Revitalised Joint Monitoring and Evaluation Commission (RJMEC), the body monitoring the R-ARCSS, observed in its report released in October that there is ‘systematic violation of the responsibility-sharing arrangements across all crucial bodies, including functionality of the executive and legislature.’ Progress on other provisions critical to South Sudan’s transition from conflict to peace, including those required for the holding of elections, remains stalled. In its report to the Reconstituted Transitional National Legislative Assembly in December 2025, RJMEC expressed ‘serious concerns that if urgent steps are not taken to expedite progress, then holding elections as scheduled in December 2026 may be extremely difficult.’

The SPLM-IO under Machar’s leadership has declared the R-ARCSS defunct following Machar’s arrest, while another faction continues to cooperate with the government. Following the detention of Riek Machar in March, the first vice president and signatory of the R-ARCSS as the leader of the SPLM-IO, the party has experienced internal divisions, with some of the members of the party coopted into and collaborating with the government.

Meanwhile, Machar and seven of his allies are standing trial before a Special Court in Juba. During its most recent session on 12 January, the court barred the public and the media from attending the proceedings, citing the need to protect prosecution witnesses. Machar and his allies have been charged with murder, treason, and crimes against humanity. Machar has rejected the charges and claimed immunity as a sitting vice president. His defence team has also challenged the court’s jurisdiction, arguing that such crimes fall within the mandate of an AU hybrid court, as stipulated under the R-ARCSS. Nevertheless, the Special Court dismissed these objections, including challenges to the constitutionality of the proceedings. It is to be recalled that the AUPSC called for the immediate and unconditional release of Machar and his wife, but the South Sudanese government rejected the appeal.

The SPLM has also experienced internal fragmentation, with veteran politician Nhial Deng Nhial suspending his membership in the party and launching a new political movement, the South Sudan Salvation Movement, which operates under the opposition United People’s Alliance led by Pagan Amum. In a surprise move in November, President Salva Kiir dismissed one of his vice presidents and the SPLM’s First Deputy Chairperson, Benjamin Bol Mel, who had been widely regarded as being prepared to be a possible successor. Although Bol Mel was promoted to the rank of general within the National Security Service’s Internal Bureau, he was subsequently stripped of his military rank and dismissed from the national security service. Kiir then reinstated James Wani Igga as vice president; Igga had been replaced by Bol Mel earlier in 2025.

President Kiir has also frequently reshuffled the cabinet through presidential decrees amid the unfolding political crisis. These reshuffles have been criticised for violating the 2018 R-ARCSS, as the President appoints and dismisses officials without consulting the other signatories, thereby undermining the power-sharing arrangements stipulated in the agreement.

In a step that is feared to cause further erosion of the collapsing R-ARCSS and in another surprise move in December, the government announced a series of amendments to the R-ARCSS following a meeting convened by President Kiir to discuss the final phase of the transition and preparations for general elections scheduled for December 2026. According to the government, the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement (SPLM), a faction of the SPLM-IO not aligned with Machar, the South Sudan Opposition Alliance (SSOA), the Former Detainees (FD), and Other Political Parties (OPP) attended the meeting.

The amendments agreed at the December meeting reportedly removed provisions linking the holding of general elections to the completion of a permanent constitution, a process that has dragged on for the past eight years. In the absence of a permanent constitution, general elections would be conducted under the Transitional Constitution adopted in 2011. The amendments also stipulate that a national population and housing census—deemed necessary for elections under the R-ARCSS—would be conducted after the elections.

The government indicated that the amendments would undergo a review process before being ratified by the national legislature. However, the SPLM-IO reportedly characterised the move as illegal, arguing that it excluded other signatories to the peace agreement and rejected the amendments in their entirety. Civil society representatives also expressed concern over the unexpected decision, calling for respect for the R-ARCSS and greater inclusion of civil society in the process.

The political crisis has contributed to a significant deterioration in South Sudan’s security situation. Reports indicate intensified fighting in various parts of the country between government and opposition forces. As political tension and fighting escalate, recent weeks have witnessed intensified hostilities in Jonglei State involving ‘repeated aerial bombardments by the South Sudan People’s Defence Forces (SSPDF), clashes with SPLM/A-IO and the reported mobilisation of armed civilian militias’, noted the UN Commission on Human Rights in its press release of 18 January 2026. This escalating fighting is compounded by local and intercommunal violence.

The spreading and intensifying violence is precipitating significant civilian casualties and destruction of critical infrastructure, including health facilities, schools, and public buildings, as well as severe limitations of humanitarian access.

These developments are aggravating an already dire humanitarian situation. According to OCHA, two-thirds of the population will require humanitarian assistance in 2026. It is reported that more than 100,000 people, predominantly women, girls, older persons and persons with disabilities, have been forcibly displaced across the state since late December 2025. The alarming humanitarian and civilian protection situation is compounded by worsening economic conditions, corruption and disease outbreaks. The ongoing conflict in neighbouring Sudan has further strained South Sudan’s already dire humanitarian situation.

As Amani Africa indicated in its briefing to the UN Security Council in November, South Sudanese civilians are the ones bearing the brunt of the deteriorating political and security situation in the country, underscoring a heightening need for reinforcing measures for the protection of civilians and humanitarian support.

At a time when the Horn of Africa is facing multiple challenges, the heightening risk of South Sudan’s relapse back to full-scale war has become a major concern, thus requiring a more robust conflict prevention effort from all quarters, not least of all the AU. In a joint statement issued on 18 December, the Troika (the United States, the United Kingdom, and Norway) expressed alarm over the widespread conflict across the country, describing it as a major setback. The Troika urged South Sudanese leaders to reverse course, halt armed attacks, immediately return to the nationwide ceasefire, and engage in sustained, leader-level dialogue. These calls were reinforced by a subsequent joint statement supported by the embassies of Canada, France, Germany, Japan, Norway, the Netherlands, Sudan, Uganda, the United Kingdom, and the United States, as well as the European Union delegation in Juba, which stressed the need for inclusive dialogue to address the country’s political and security crisis.

It is to be recalled that the AUPSC encouraged the continued engagement of the AU High-Level Ad Hoc Committee for South Sudan (C5) in supporting the constitution-making process and preparations for the December 2026 elections. A C5 delegation comprising representatives from South Africa, Algeria, Chad, Nigeria, and Rwanda visited Juba on 14 January. It held high-level meetings with South Sudanese authorities to discuss the political situation, implementation of the R-ARCSS, and preparations for general elections, among other issues. The AUPSC is expected to receive an update on the outcome of the visit.

The expected outcome of the session is a communiqué. The PSC is expected to express grave concern over the deteriorating political and security situation, the systematic violations of the R-ARCSS and the rising danger of the country’s relapse to full-scale civil war. It may condemn and call for an unconditional end to the indiscriminate use of violence and violence against civilians. The PSC may also reaffirm that the R-ARCSS remains the most viable framework for sustainable peace and stability in South Sudan and may urge both parties to recommit to the permanent ceasefire and transitional roadmap. It could also call for the release of all political detainees and restoration of political dialogue. As a critical step towards restoration of stability and implementation of R-ARCSS, it may call for an independent investigation of incidents of violations of the revitalised peace agreement, including the March 2025 incident in Nasir, through a mechanism that is put in place by the UN-AU-IGAD. It could also call for full reactivation of the Ceasefire and Transitional Security Arrangements Monitoring and Verification Mechanism (CTSAMVM) to ensure compliance with the ceasefire. To ensure high-level and sustained engagement for preventing South Sudan’s relapse back to full scale civil war, the PSC may reiterate its request for the AU Commission to maintain sustained engagement, including possibly appointing a High-Level Envoy to work jointly with IGAD, the C5, and the Trilateral Mechanism to facilitate direct dialogue between President Kiir and the SPLM-IO leader and signatory to the R-ARCSS Machar.

……………………………………………

For additional reference, check the briefing Amani Africa delivered to the UN Security Council from the link here https://amaniafrica-et.org/amani-africa-tells-the-unsc-to-deploy-preventive-measures-with-urgency-and-decisiveness-to-pull-south-sudan-from-the-brink/

The press statement by the UN Commission for Human Rights in South Sudan, dated 18 January 2026, can also be found at the following link:

https://x.com/uninvhrc/status/2012798544801906798.

Consideration of the situation in Guinea

Consideration of the situation in Guinea

Date | 21 January 2026

Tomorrow (22 January), the African Union (AU) Peace and Security Council (PSC) will convene a session to consider the situation in Guinea.

The session will commence with an opening statement by the Chairperson of the PSC for the month, Jean-Léon Ngandu Ilunga, Permanent Representative of the Democratic Republic of the Congo to the AU, followed by a statement from Bankole Adeoye, Commissioner for Political Affairs, Peace and Security (PAPS). Guinea’s representative may also deliver a statement following the closed session.

The session takes place against the backdrop of recent developments marking the formal conclusion of Guinea’s transition following the September 2021 military coup. These developments culminated in the presidential election held on 28 December 2025. The coup leader, General Mamadi Doumbouya, was declared the winner with 86.72 per cent of the vote following the proclamation of the final results by the Supreme Court on 4 January 2026, and was subsequently sworn in as President on 17 January.

In a communiqué released on 4 January, the Chairperson of the AU Commission, Mahamoud Ali Youssouf, extended his ‘warmest congratulations’ to the President-elect of Guinea. He commended the Guinean people for demonstrating political maturity through peaceful participation in the electoral process, and called on the AU and the international community to assess the situation in the country with a view to lifting the sanctions imposed on Guinea. He stated that such a step would reflect the progress achieved and help create favourable conditions for the implementation of the roadmap aimed at rebuilding and modernising the state for the well-being of the Guinean people.

A similar position was reflected in the Preliminary Statement of the AU Election Observation Mission, led by former President of Burundi and member of the AU Panel of the Wise, Domitien Ndayizeye. The Mission concluded that the election was conducted in a ‘peaceful, orderly and credible environment, consistent with relevant international standards and the national legal framework.’ On this basis, it recommended that the AU consider lifting the sanctions imposed on Guinea as a gesture of increased solidarity, to encourage the acceleration and successful completion of structural reforms, support national reconciliation, and create a conducive environment for forthcoming elections as drivers of social stabilisation and democratic consolidation.

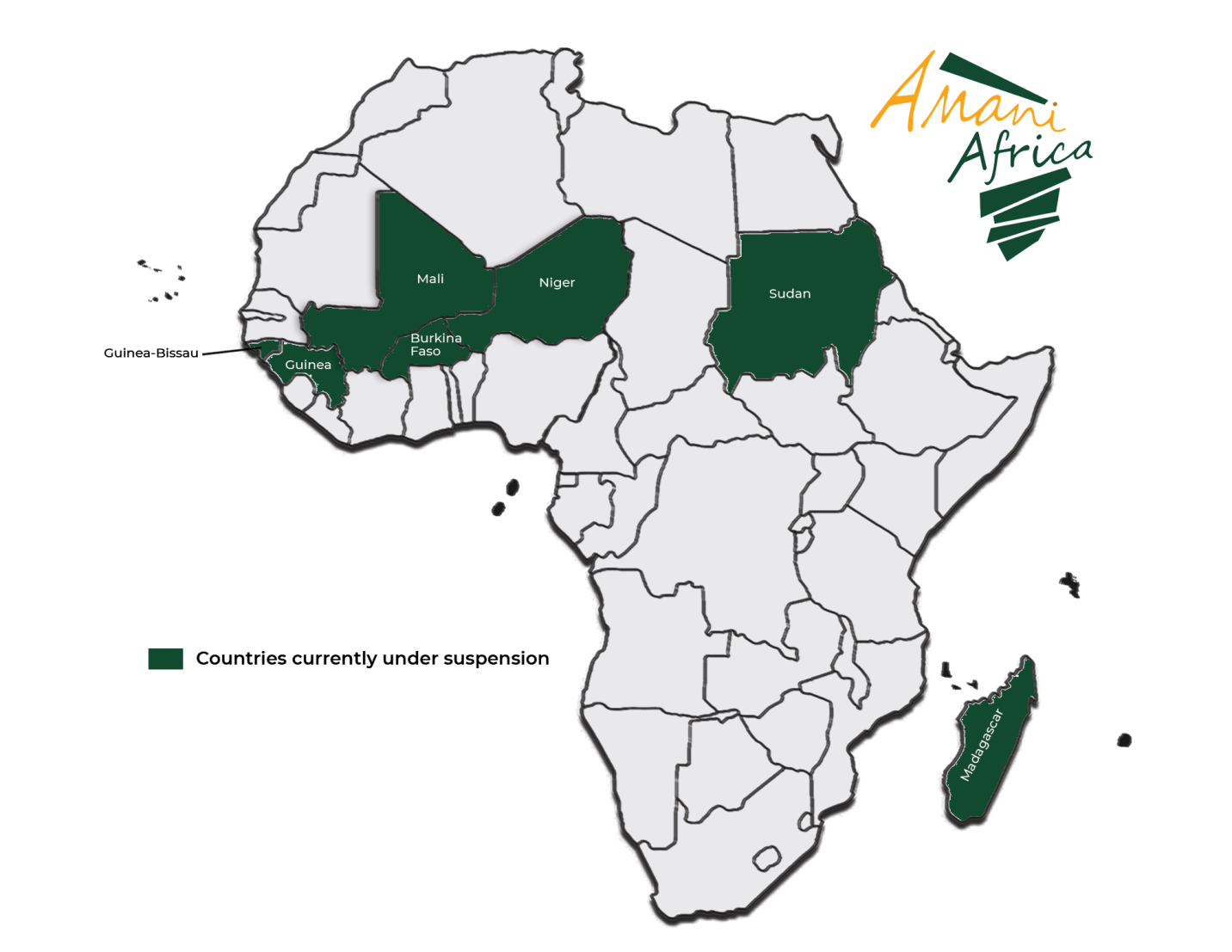

Tomorrow’s session thus unfolds in the context of these calls by the Chairperson of the Commission and the AU Election Observation Mission for the lifting of the sanctions imposed by the PSC at its 1030th session of 10 September 2021, following the unconstitutional change of government in the country. Mirroring the approach taken in the case of Gabon—where suspension was lifted after a presidential election despite its inconsistency with the AU’s anti-coup norm barring coup perpetrators from contesting elections—the PSC is expected to lift the sanctions and bring Guinea back into the AU fold.

Guinea was suspended by the PSC on 10 September 2021 from participation in all AU activities following the military coup of 5 September 2021 led by the current President, General Mamadi Doumbouya. Since then, the political transition in the country experienced delays, notwithstanding the two-year transition period agreed between Guinea and the regional bloc, ECOWAS, in October 2022. However, in 2025, Guinea took steps to complete the political transition.

A constitutional referendum was held on 21 September 2025, laying the foundation for the entry into force of a new Constitution adopted by the people and promulgated on 26 September. The Constitution amended the legal framework to allow members of the ruling military authorities to stand as candidates and extended the presidential term to seven years, renewable once. A new Electoral Code was also adopted and promulgated on 27 September 2025. On 28 December, Guinea organised the presidential election, a key milestone in the political transition and a major step toward the restoration of constitutional order in the country.

The PSC conducted a field mission to Guinea on 30 and 31 May 2025, during the chairship of Sierra Leone, to encourage the authorities to complete the transition. During the mission, it is recalled that the Guinean authorities requested that the AU consider lifting sanctions following the constitutional referendum in September, in order to facilitate re-engagement with the international community and access to vital partnerships for socioeconomic development. However, both the report of the field mission and the communiqué adopting it alluded that the conduct of the presidential election in December—rather than the constitutional referendum—would mark the formal end of the transition and trigger the lifting of sanctions.

In the communiqué adopted at its 1284th session, the PSC requested the AU Commission to engage with the Guinean transition authorities to identify areas of support and provide the necessary technical and financial assistance, particularly for the constitutional referendum and the preparation of the general elections scheduled for December. In follow-up to this request, the Commission deployed a short-term Election Observation Mission to Guinea from 20 December 2025 to 1 January 2026, composed of 62 observers and led by Mr Domitien Ndayizeye.

As PSC members prepare to consider the lifting of Guinea’s suspension, they will be confronted with the question of how to reconcile such a decision with Article 25(4) of the African Charter on Democracy, Elections and Governance (ACDEG), which explicitly prohibits perpetrators of unconstitutional changes of government from participating in elections held to restore democratic order or from holding positions of responsibility in political institutions. This, however, is not the first time the PSC has faced this dilemma. At its 442nd session in June 2014, when lifting Egypt’s suspension, the PSC explicitly stated that the decision was taken with the ‘understanding that this does not constitute a precedent’ regarding compliance with Article 25(4) of the Charter.

More recently, in the case of Gabon, the PSC at its 1277th session held on 30 April 2025 lifted the country’s suspension following the 12 April presidential election, which resulted in the election of Brice Oligui Nguema—the leader of the August 2023 military seizure of power—without reiterating the non-precedential caveat or reaffirming the relevance of Article 25(4). This signalled a notable shift in the PSC’s approach, with growing emphasis on reintegrating countries suspended following military coups into the AU fold, even at the expense of weakening the Union’s own anti-coup norms. The prevailing sentiment within the PSC appears increasingly pragmatic and flexible, marking a departure from the AU’s declared policy of zero tolerance for unconstitutional changes of government.

Lifting Guinea’s suspension without addressing its compatibility with Article 25(4) of ACDEG would have serious implications—not only for the AU’s normative stance on unconstitutional changes of government, but also for the precedent it sets for other sanctioned contexts. It would raise fundamental questions about the applicability of Article 25(4) and the message conveyed to militaries across the continent. If those who seize power through military coups can ultimately secure legitimacy through elections endorsed by the AU, it risks incentivising unconstitutional seizures of power by altering the perceived balance between the risks and rewards of military intervention in politics.

In this context, the critical questions raised in our previous analyses of the PSC’s approach in the case of Gabon remain equally relevant to Guinea. When considering the lifting of Guinea’s suspension, the issue should not be limited to whether the completion of the electoral process constitutes the restoration of constitutional order. It should also address how the PSC intends to manage the implications of this decision in relation to Article 25(4). At a minimum, the PSC could reiterate the formulation adopted at its 442nd session, emphasising the continued relevance of Article 25(4) and clarifying that the lifting of Guinea’s suspension does not constitute a precedent for future cases.

The expected outcome of the session is a communiqué. The PSC is likely to commend the conduct of the presidential election held on 28 December 2025 and may congratulate Mamadi Doumbouya on his election as President. In line with the calls by the Chairperson of the AU Commission and the AU Election Observation Mission, the PSC is also expected to lift Guinea’s suspension and invite the country to immediately resume participation in AU activities. However, it remains unclear whether the PSC will explicitly reaffirm the relevance of Article 25(4) of ACDEG and clarify the non-precedential nature of its decision—as it did in 2014—or whether it will follow the approach adopted in its 1277th session on Gabon, thereby tacitly tolerating a breach of this provision.

The gathering storm facing Africa in 2026: Entrenching conflicts, Fractured Order, and eroding agency

The gathering storm facing Africa in 2026: Entrenching conflicts, Fractured Order, and eroding agency

Date | 14 January 2026

Abdul Mohammed, Former Senior UN Official and Chief of Staff of AU High-level Panel on Sudan

Solomon Ayele Dersso, PhD, Founding Director, Amani Africa

Africa is entering 2026 not at a moment of transition, but at a moment of reckoning. Across the continent, armed conflict, state fragmentation, humanitarian collapse, economic distress, climate shocks, democratic erosion, and geopolitical entanglement are converging with a simultaneity and intensity unseen in recent decades. What distinguishes this moment is not the presence of crisis per se, but the growing risk that instability is becoming structural rather than episodic—normalized rather than exceptional.

This reckoning is unfolding against the backdrop of a deepening global disorder. The international system itself is unraveling at alarming speed. Established norms, institutions, and rules are eroding, replaced by ad hoc power politics, coercive economic statecraft, and fierce geopolitical competition. This disorder is not stabilizing. It is accelerating—and its consequences are ominous, particularly for Africa and others in the global South as events on Christmas day in Nigeria and on 6 January in Venezuela illustrate.

Parts of the Global South are struggling, unevenly and imperfectly, to reposition themselves in response to this turbulence. The question for Africa is, as SRSG and Head of UN Office to the AU Parfait Onanga-Anyanga recently put it, will it position itself to negotiate collective interests amidst this prolific and plural competition, or will African countries get picked off one by one?

Africa, however, enters 2026 with no clear evidence of serious, collective, continent-wide strategic reflection on how to navigate the emerging global order. As captured in a recent Amani Africa policy brief, Africa’s engagement is characterized by fragmentation, operating on the basis of ‘a patchwork of’ individual, often competing foreign policies of African states. While individual states and sub-regions may be engaging externally, they are largely doing so through transactional, bilateral, and short-term calculations, rather than through a shared Pan-African vision or common strategic posture.

The result is deeply concerning. Fierce competition among middle powers and major powers in Africa is deliberately fragmenting the continent, integrating African states, sub-regions, and institutions—by default or by design—into rival spheres of influence, one by one. This process steadily undermines Africa’s capacity to articulate and defend common positions, erodes continental solidarity, and dismantles the very foundations of collective action. These conditions are compounded due to the absence of a collective policy for governing its relations with global actors.

As Nkrumah prophesied on the dire consequences of disunity, without collectivity, Africa will not be a shaper of the emerging global order. It will be relegated to a footnote—reacting, adapting, and absorbing the consequences of decisions made elsewhere. In such a scenario, Pan-Africanism itself becomes hollow, reduced to rhetoric rather than strategy, symbolism rather than power.

The Geography of Africa’s Polycrisis

From the Horn of Africa to the Sahel and the Great Lakes region, conflict has ceased to be contained within national borders or finite political disputes, as extensively documented in Amani Africa signature publications (here and here). Instead, it has become regionalized, protracted, and embedded within broader political and economic systems. These regions now function as interconnected theaters of instability—zones where internal fragmentation intersects with external intervention, and where war increasingly sustains itself.

Arms flows, armed groups, war economies, displaced populations, and political narratives move fluidly across borders. Violence migrates, mutates, and reproduces itself. Local wars acquire continental and global consequences, disrupting trade corridors, fueling forced migration, and drawing in ever more external actors.

From Contested Wars to Permanent War Systems

In its signature publication accompanying the African Union summit, a report by Amani Africa poignantly pointed out that Africa has entered a new era of insecurity and instability. The nature of war in Africa has fundamentally changed. Contemporary conflicts are no longer primarily about seizing state power or achieving decisive military victory. They increasingly resemble wars of permanence—open-ended struggles sustained by political fragmentation, economic incentives, and geopolitical rivalry.

Armed actors have proliferated and diversified. States confront militias, paramilitaries, mercenary formations, and hybrid security forces, often while relying on similar actors themselves. Authority is diffused, accountability diluted, and violence outsourced.

Conflict has become economically rational. Smuggling, trafficking, illicit taxation, aid diversion, and control of trade routes sustain armed groups and political elites alike. Entire war economies have taken root, making peace politically difficult and economically threatening for those who profit from disorder.

External entanglement has intensified. Middle powers and global rivals increasingly treat African conflict zones as arenas of strategic competition. Access to resources, ports, markets, and military facilities frequently outweigh commitments to peace.

Civilians are no longer incidental victims, as exemplified by events in Sudan which are documented in Amani Africa’s report on prioritizing the protection of civilians. Displacement, starvation, and terror are increasingly deployed as strategies of control. Norms have eroded. Ceasefires rarely hold. Agreements no longer bind. Mediation is widely mistrusted.

Elections Without Peace: Democracy as a Risk Multiplier

As Africa approaches 2026, a dense calendar of elections looms across fragile and polarized contexts. Elections conducted without political settlement, security guarantees, institutional trust, and political inclusion do not endure. They redistribute conflict rather than resolve it.

Consistent with the African Charter on Democracy, Elections and Governance, the African Union must urgently revisit its election observation, validation, and certification practices. Recent controversial elections and rulings have eroded public trust in electoral politics, particularly in the context of upcoming elections in 2026.

The Collapse of Multilateral Authority

At precisely the moment Africa needs collective action, its multilateral institutions are at their weakest. Political capture, failure to articulate clear vision and mobilize consensus of member states, inconsistency, underfunding, and external bypassing have eroded credibility and enforcement capacity.

Peace initiatives are increasingly brokered outside African multilateral frameworks. They tend to be driven by transactional mindsets that prioritize short-term deals over norms and durable political settlements. This trend poses a mortal danger to Africa’s peace and security architecture, as the loss of leadership of the African Union (AU)on many files clearly attests.

Toward a Reform Agenda: Reclaiming Politics, Collectivity, and Pan-African Agency

This trajectory is not inevitable. But reversing it requires decisive collective action.

Africa must urgently undertake a serious, collective strategic reflection on its position in the emerging global order. The AU institutional reform offers an opportunity but only if it is done in a manner that breaks from the failed business as usual approach of the past years. The AU, together with regional economic communities, must craft and articulate a common Pan-African strategy to resist fragmentation and reclaim agency.

The primacy of politics must guide multilateral action. Conflict prevention and resolution need to be revitalized, anchored on robust diplomacy for peace. Peacemaking, mediation, and peacebuilding—not transactional dealmaking—must remain the core mandate of Africa’s multilateral institutions. Ceasefires are necessary but insufficient; they are steps toward political settlement, not substitutes for it.

Conflicts that are regional in nature require integrated regional strategies. Enforcement must matter. Decisions without consequences erode credibility.

War economies must be dismantled. Conflict financing networks, trafficking routes, and external sponsorship must be disrupted through coordinated regional and international action.

Peace initiatives must be principled and based on courageous leadership and impartial but solidly supported diplomatic strategy.

Civilians must be re-centered. Peace processes that exclude social forces, youth, women, and displaced populations lack legitimacy and durability.

Finally, elections must be subordinated to peace, not the reverse. No more elections without security guarantees, political inclusion, and consensus on the rules of the game.

2026: A Line in the Sand

Africa is approaching a decisive threshold. If current trends persist, 2026 may be remembered as the moment when permanent war became structurally entrenched and Africa’s collective voice fatally weakened.

The future remains salvageable—but only if serious reform based on recommitment to and robust defense of AU norms replaces ritual, collective strategy replaces fragmentation, and peace and Pan-Africanism are reclaimed as deliberate political choices rather than rhetorical aspirations bereft of resolve.

The content of this article does not represent the views of Amani Africa and reflect only the personal views of the authors who contribute to ‘Ideas Indaba’

The gathering storm facing Africa in 2026: Entrenching conflicts, Fractured Order, and eroding agency

The gathering storm facing Africa in 2026: Entrenching conflicts, Fractured Order, and eroding agency

Date | 14 January 2026

Abdul Mohammed, Former Senior UN Official and Chief of Staff of AU High-level Panel on Sudan

Solomon Ayele Dersso, PhD, Founding Director, Amani Africa

Africa is entering 2026 not at a moment of transition, but at a moment of reckoning. Across the continent, armed conflict, state fragmentation, humanitarian collapse, economic distress, climate shocks, democratic erosion, and geopolitical entanglement are converging with a simultaneity and intensity unseen in recent decades. What distinguishes this moment is not the presence of crisis per se, but the growing risk that instability is becoming structural rather than episodic—normalized rather than exceptional.

This reckoning is unfolding against the backdrop of a deepening global disorder. The international system itself is unraveling at alarming speed. Established norms, institutions, and rules are eroding, replaced by ad hoc power politics, coercive economic statecraft, and fierce geopolitical competition. This disorder is not stabilizing. It is accelerating—and its consequences are ominous, particularly for Africa and others in the global South as events on Christmas day in Nigeria and on 6 January in Venezuela illustrate.

Parts of the Global South are struggling, unevenly and imperfectly, to reposition themselves in response to this turbulence. The question for Africa is, as SRSG and Head of UN Office to the AU Parfait Onanga-Anyanga recently put it, will it position itself to negotiate collective interests amidst this prolific and plural competition, or will African countries get picked off one by one?

Africa, however, enters 2026 with no clear evidence of serious, collective, continent-wide strategic reflection on how to navigate the emerging global order. As captured in a recent Amani Africa policy brief, Africa’s engagement is characterized by fragmentation, operating on the basis of ‘a patchwork of’ individual, often competing foreign policies of African states. While individual states and sub-regions may be engaging externally, they are largely doing so through transactional, bilateral, and short-term calculations, rather than through a shared Pan-African vision or common strategic posture.

The result is deeply concerning. Fierce competition among middle powers and major powers in Africa is deliberately fragmenting the continent, integrating African states, sub-regions, and institutions—by default or by design—into rival spheres of influence, one by one. This process steadily undermines Africa’s capacity to articulate and defend common positions, erodes continental solidarity, and dismantles the very foundations of collective action. These conditions are compounded due to the absence of a collective policy for governing its relations with global actors.

As Nkrumah prophesied on the dire consequences of disunity, without collectivity, Africa will not be a shaper of the emerging global order. It will be relegated to a footnote—reacting, adapting, and absorbing the consequences of decisions made elsewhere. In such a scenario, Pan-Africanism itself becomes hollow, reduced to rhetoric rather than strategy, symbolism rather than power.

The Geography of Africa’s Polycrisis

From the Horn of Africa to the Sahel and the Great Lakes region, conflict has ceased to be contained within national borders or finite political disputes, as extensively documented in Amani Africa signature publications (here and here). Instead, it has become regionalized, protracted, and embedded within broader political and economic systems. These regions now function as interconnected theaters of instability—zones where internal fragmentation intersects with external intervention, and where war increasingly sustains itself.

Arms flows, armed groups, war economies, displaced populations, and political narratives move fluidly across borders. Violence migrates, mutates, and reproduces itself. Local wars acquire continental and global consequences, disrupting trade corridors, fueling forced migration, and drawing in ever more external actors.

From Contested Wars to Permanent War Systems

In its signature publication accompanying the African Union summit, a report by Amani Africa poignantly pointed out that Africa has entered a new era of insecurity and instability. The nature of war in Africa has fundamentally changed. Contemporary conflicts are no longer primarily about seizing state power or achieving decisive military victory. They increasingly resemble wars of permanence—open-ended struggles sustained by political fragmentation, economic incentives, and geopolitical rivalry.

Armed actors have proliferated and diversified. States confront militias, paramilitaries, mercenary formations, and hybrid security forces, often while relying on similar actors themselves. Authority is diffused, accountability diluted, and violence outsourced.

Conflict has become economically rational. Smuggling, trafficking, illicit taxation, aid diversion, and control of trade routes sustain armed groups and political elites alike. Entire war economies have taken root, making peace politically difficult and economically threatening for those who profit from disorder.

External entanglement has intensified. Middle powers and global rivals increasingly treat African conflict zones as arenas of strategic competition. Access to resources, ports, markets, and military facilities frequently outweigh commitments to peace.

Civilians are no longer incidental victims, as exemplified by events in Sudan which are documented in Amani Africa’s report on prioritizing the protection of civilians. Displacement, starvation, and terror are increasingly deployed as strategies of control. Norms have eroded. Ceasefires rarely hold. Agreements no longer bind. Mediation is widely mistrusted.

Elections Without Peace: Democracy as a Risk Multiplier

As Africa approaches 2026, a dense calendar of elections looms across fragile and polarized contexts. Elections conducted without political settlement, security guarantees, institutional trust, and political inclusion do not endure. They redistribute conflict rather than resolve it.

Consistent with the African Charter on Democracy, Elections and Governance, the African Union must urgently revisit its election observation, validation, and certification practices. Recent controversial elections and rulings have eroded public trust in electoral politics, particularly in the context of upcoming elections in 2026.

The Collapse of Multilateral Authority

At precisely the moment Africa needs collective action, its multilateral institutions are at their weakest. Political capture, failure to articulate clear vision and mobilize consensus of member states, inconsistency, underfunding, and external bypassing have eroded credibility and enforcement capacity.

Peace initiatives are increasingly brokered outside African multilateral frameworks. They tend to be driven by transactional mindsets that prioritize short-term deals over norms and durable political settlements. This trend poses a mortal danger to Africa’s peace and security architecture, as the loss of leadership of the African Union (AU)on many files clearly attests.

Toward a Reform Agenda: Reclaiming Politics, Collectivity, and Pan-African Agency

This trajectory is not inevitable. But reversing it requires decisive collective action.

Africa must urgently undertake a serious, collective strategic reflection on its position in the emerging global order. The AU institutional reform offers an opportunity but only if it is done in a manner that breaks from the failed business as usual approach of the past years. The AU, together with regional economic communities, must craft and articulate a common Pan-African strategy to resist fragmentation and reclaim agency.

The primacy of politics must guide multilateral action. Conflict prevention and resolution need to be revitalized, anchored on robust diplomacy for peace. Peacemaking, mediation, and peacebuilding—not transactional dealmaking—must remain the core mandate of Africa’s multilateral institutions. Ceasefires are necessary but insufficient; they are steps toward political settlement, not substitutes for it.

Conflicts that are regional in nature require integrated regional strategies. Enforcement must matter. Decisions without consequences erode credibility.

War economies must be dismantled. Conflict financing networks, trafficking routes, and external sponsorship must be disrupted through coordinated regional and international action.

Peace initiatives must be principled and based on courageous leadership and impartial but solidly supported diplomatic strategy.

Civilians must be re-centered. Peace processes that exclude social forces, youth, women, and displaced populations lack legitimacy and durability.

Finally, elections must be subordinated to peace, not the reverse. No more elections without security guarantees, political inclusion, and consensus on the rules of the game.

2026: A Line in the Sand

Africa is approaching a decisive threshold. If current trends persist, 2026 may be remembered as the moment when permanent war became structurally entrenched and Africa’s collective voice fatally weakened.

The future remains salvageable—but only if serious reform based on recommitment to and robust defense of AU norms replaces ritual, collective strategy replaces fragmentation, and peace and Pan-Africanism are reclaimed as deliberate political choices rather than rhetorical aspirations bereft of resolve.

The content of this article does not represent the views of Amani Africa and reflect only the personal views of the authors who contribute to ‘Ideas Indaba’