THE SEQUENCE, PROCEDURE, DYNAMICS AND SCENARIOS FOR THE 2025 AU COMMISSION LEADERSHIP ELECTIONS

THE SEQUENCE, PROCEDURE, DYNAMICS AND SCENARIOS FOR THE 2025 AU COMMISSION LEADERSHIP ELECTIONS

Date | 7 February 2025

INTRODUCTION

The elections of the African Union (AU) Commission leadership are expected to dominate the 38th Ordinary Session of the African Union (AU) Assembly (AU Summit) scheduled to take place from 12 to 16 February 2025. The elections of the AU Commission leadership are significant on their own, considering the influence that they wield in the decision-making processes of the AU. Additionally, and perhaps more significantly, these elections occupy special significance on account of the timing and geopolitical context in which they are being held.

Monthly Digest on The African Union Peace And Security Council - December 2024

Monthly Digest on The African Union Peace And Security Council - December 2024

Date | December 2024

In December 2024, the Republic of Djibouti chaired the African Union (AU) Peace and Security Council (PSC). During the month, the Council planned to conduct four substantive sessions covering five agenda items, and an informal consultation on countries in political transition, with only one session dedicated to country-specific situation. The remaining four items focused on thematic matters. Except one session held at ministerial level, all the sessions of the month were held at the ambassadorial level.

Exclusive interview: Mr. Brian Kagoro, Managing Director, Programs, OSF

Exclusive interview: Mr. Brian Kagoro, Managing Director, Programs, OSF

Feb 5, 2025

The new AU Somalia mission (AUSSOM) is ATMIS by another name but with more problems

The new AU Somalia mission (AUSSOM) is ATMIS by another name but with more problems

Date | 5 February 2025

A month after the ‘new’ African Union (AU) Mission to Somalia, the AU Support and Stabilisation Mission in Somalia (AUSSOM) became de jure operational effective 1 January 2025, following the 27 December 2024 adoption of UN Security Council Resolution 2767, a number of issues critical to the mission remain unresolved.

Despite being declared de jure operational, for all practical purposes AUSSOM is actually AU Transition Mission in Somalia (ATMIS) by other name. What took place on 1 January is nothing more than change of name. AUSSOM inherited all the problems of ATMIS. Importantly, it also faces more dire challenges.

ATMIS came into being and lived through major financial woes. As the PSC’s report to the February 2024 AU summit noted, the financial shortfall facing ATMIS, including as a result of the extension of the drawdown of troops, was estimated to be ‘over $100 million by the time the ATMIS forces exit on 31 December 2024.’ AUSSOM comes into a de jure operation with a major financial shortfall. The financing of the mission remains unsettled, and it is far from clear if it would find a satisfactory resolution unless the UN Security Council decides to use AUSSOM as a test case for implementing Resolution 2719.

As with ATMIS, the exit strategy for the post-ATMIS mission is predicated on

- the achievement by Somalia Security Forces (SSF) of a level of capability good enough for taking over security responsibility from the AU mission,

- the erosion of Al Shabaab’s capacity to a point where it no longer poses serious threats, and

- most notably, the consolidation of national political cohesion and settlement and the expansion of state authority through enhanced legitimate local governance structures that deliver public services.

All of these considerations depend on the capacity of first and foremost the Federal Government of Somalia (FGS) and generally the wider Somalia political and social forces to shoulder effectively their part of the responsibility much better than they have done in recent years.

In terms of force generation and building effective capabilities of the SSF, progress remains slow. It is this lack of progress that led the FGS to requesting severally the postponement of the exit of designated size of ATMIS troops at various phases of the mission’s drawdown.

Politically, the state of relations between FGS and Federal Member States continues to face serious strains. Since January 2023, Puntland declared that it would act independently of Mogadishu. Jubaland also severed ties with Mogadishu following mounting tensions with the federal government. The situation subsequently led to an armed confrontation between the federal government forces and the Jubaland regional forces in Ras Kamboni, the southernmost tip of Somalia in lower Juba bordering Kenya. In other words, the lack of political consensus and cohesion remains the major missing link for meeting the benchmarks set for AUSSOM, as was the case for ATMIS. The initial joint AU-UN strategic assessment report on post-ATMIS security arrangements – (prepared and submitted in May 2024 but could not be considered by the PSC due to objection by the Somalia Government due to the politically unpalatable candidness of the technical assessment about the security situation) – thus pointed out that ‘[unless there is political consensus, on the implementation of major decisions agreed at the national level, capacity generation and integration will not be achieved in the short, medium and long term after 2024.’ (own emphasis)

The phased implementation of AUSSOM was initially envisaged to have a pre-mission/transitional phase, involving the completion of ATMIS phases and the parallel preparation of the reorganisation of the areas of operations and troop deployments of AUSSOM. As such, this transitional phase was meant to run for the duration of the last two phases of ATMIS, namely Phase III and Phase IV, concluding on 31 December 2024.

However, as with ATMIS, the implementation of the pre-mission phase of AUSSOM did not proceed as planned. The lack of progress in some of the activities concerning the pre-mission phase meant that AUSSOM was declared operational on 1 January merely by a force of legal determination, with the pre-mission phase becoming phase I of the ‘new’ mission as depicted above.

As if all of these issues are not enough, AUSSOM faces new challenges, additional to those ATMIS encountered. First, if the lack of consensus between Somalia and Burundi persists and Burundi over troop allocation persists and Burundi leaves, AUSSOM will lose the operational knowledge and experience that Burundi built (with heavy price) owing to its participation in the AU mission in Somalia since 2007. This departure of experience may mean increased vulnerability of the mission.

Second, AUSSOM got entangled in a geopolitical tussle that arose from the tension that erupted between Somalia and Ethiopia over the Memorandum of Understanding the latter signed with Somaliland for securing access to the sea. The ensuing disagreement over the continuation of Ethiopia as a troop contributing country meant that AUSSOM was declared operational without settling the question of troop contributors. It was also in this context that Egypt emerged into the scene proposed to be the new troop contributor to AUSSOM, raising fears of this injecting the tension over the Nile into the AUSSOM ecosystem.

Third, uncertainty over the size and location of pending troop contribution means that there is also lack of clarity on operational set up and mission design and command and control of AUSSOM. As a result and as Paul Williams explained, the kind of mission capabilities that AUSSOM requires and the kind of logistics support to be availed for the mission from the UN also remains uncertain.

Fourth, on the composition and contribution of troops for AMISOM/ATMIS, the AU, as the mandating authority responsible for the mission, was in the lead in the negotiations over troop contribution and mission design. This has helped to minimise the exposure of the mission to Somalia’s internal and external political contestations. For AUSSOM, AU took a backseat. In its place, the host country, Somalia, took the lead in negotiating ‘bilaterally’ contribution of troops to AUSSOM. The result is that the process of operationalisation of AUSSOM has become much more politicised than AMISOM/ATMIS, thereby creating the risk of reduction of the effectiveness of AUSSOM. During its 1238th session, the PSC directed ‘Chairperson of the African Union Commission to liaise with the Federal Government of Somalia, as the host country, on the composition of the Mission.’ It was only on 23 January that the AU Commission convened the meeting of states that expressed interest to contribute troops to AUSSOM, namely Burundi, Djibouti, Egypt, Ethiopia, Kenya and Uganda.

It remains unclear whether the outcome of this meeting would change what transpired thus far in terms of the allocation by Somalia of troops for troop contributors, including, most notably, the participation of Burundi.

The combination of the old and relatively new challenges means that AUSSOM emerges not only into a more difficult beginning but also faces a more uncertain prospect than ATMIS. It is in the interest of international peace and security and Somalia that the AU is allowed to assume its full responsibility and lead on the negotiations for resolving the outstanding issues concerning AUSSOM. Leaving such a critical process to the dictates of the host country, which is entangled in competing interests from various actors, jeopardises the mission’s effectiveness while risking reversal of hard-won gains.

Provisional Programme of Work of the Peace and Security Council for February 2025

Provisional Programme of Work of the Peace and Security Council for February 2025

Date | February 2025

Equatorial Guinea will assume the role of chairing the African Union (AU) Peace and Security Council (PSC) for the month of February. The Provisional Programme of Work for the month prepared under Equatorial Guinea’s leadership envisages three substantive sessions. This is much less than the usual number of sessions the PSC convenes in the course of the month. The sessions are scheduled to take place at all three levels.

The first session of the PSC on 4 February will be convened at the ministerial level for a session on maritime security in the Gulf of Guinea. Since 2013, the PSC has held various sessions addressing maritime insecurity in the Gulf of Guinea. The Council last addressed this issue during its 1209th session held on 18 April 2024. During the session, the PSC emphasised the profound impact of maritime insecurity on the Continental Blue Economy and the implementation of the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA). The PSC had also requested an assessment of the implementation of existing maritime security instruments, for which it may seek to get a status update during this session. Given the proliferation of maritime security initiatives, it is of interest for the PSC to request a comprehensive mapping exercise to harmonise efforts, maximise resources and ensure stronger engagement with all relevant regional bodies in enhanced intelligence sharing, joint implementation of robust counter-terrorism measures. The session may also follow up on the activation of the Committee of the Heads of African Navies and Coastguards (CHANS), which the Council had previously emphasised. The PSC may also seek to follow up on the developments of the first ASF maritime exercise, which is still pending.

On 14 February, the PSC will convene a Summit-level meeting to Consider the Situation in Sudan. The last time Sudan was formally on the PSC’s agenda was on 9 October 2024, during its 1235th session, which examined the report of the PSC’s field mission to Port Sudan and Cairo. That visit allowed the Council to engage with Sudanese stakeholders, including the Sovereign Council of the Transitional Government. In discussions with Sovereign Council head and SAF Commander Abdel Fattah Al Burhan, the PSC heard SAF’s perspective on the war, the RSF’s responsibility in the conflict, and Burhan’s expectations for peace. A key contentious issue raised when the PSC held the session to consider the report was the lifting of Sudan’s suspension. More recently, on 31 October, the PSC addressed Sudan again under Any Other Business (AOB) during its 1242nd session, which primarily focused on Women, Peace, and Security. That discussion was triggered by escalating violence in Al-Jazirah State and Al-Damazein following the defection of an RSF commander to the SAF. Since then, the conflict has continued, with the SAF retaking Wad Medani in early January 2025 and advancing into Khartoum while fighting rages on in North Darfur around El Fasher. Civilians remain at grave risk, facing deliberate attacks, torture, summary executions, and widespread sexual violence. The humanitarian crisis has worsened, with nearly half of Sudan’s population—24.6 million people—facing acute food insecurity and famine conditions continuing to expand and deepen. The RSF has been accused of mass atrocities, including genocide. AU Special Envoy on the Prevention of Genocide, Adama Dieng, has also expressed deep concerns over escalating violence, including mass killings, summary executions, abductions, and sexual violence, warning that the full scale of atrocities remains obscured due to a telecommunications blackout. Meanwhile, diplomatic efforts have been scattered, with Türkiye being a recent addition to the already crowded arena of mediation offering to mediate.

On 18 February, the Council will consider and adopt the Provisional Programme of Work for the month of March.

The last session for the month is an ambassadorial-level session on the fight against the use of child soldiers, scheduled to take place virtually on 20 February. The Council’s last session on the matter was during its 1202nd meeting held on 27 February 2024. At the time, it expressed deep concern over the increasingly asymmetrical nature of armed conflicts in Africa that heightened the vulnerability of children to grave rights violations, particularly their recruitment and use by armed forces, non-state armed groups, and terrorist organisations. In the upcoming session, it is expected that the Council will follow up on the decisions it had passed to develop a best practice document of reference to prevent and end the recruitment and use of child soldiers by armed groups and operationalise Child Protection Architecture. Additionally, the session presents an opportunity for taking stock of trends and developments around challenges to the protection of children in the various conflict settings on the continent and the factors and actors responsible for the plight of children affected by conflicts; this session also presents the PSC the opportunity to review the status of implementation of the various decisions it adopted on the protection of children during armed conflicts.

The PSC, during its emergency session on the situation in Eastern DRC on 28 January had also proposed to convene a PSC session on the situation in Eastern DRC at the Head of State and Government level on the margins of the AU Summit taking place 15 – 16 February 2025. However, this proposed session is not indicated in the Provisional Programme of Work.

On 15-16 February during the summit, the Chairperson of the PSC and the Commissioner for PAPS will present the Report on the activities of the PSC for 2024 and the state of peace and security in Africa.

The Withdrawal of AES from ECOWAS: An opportunity for re-evaluating existing instruments for regional integration?

The Withdrawal of AES from ECOWAS: An opportunity for re-evaluating existing instruments for regional integration?

Date | 31 January 2025

Colonel Festus B. Aboagye (Retired)

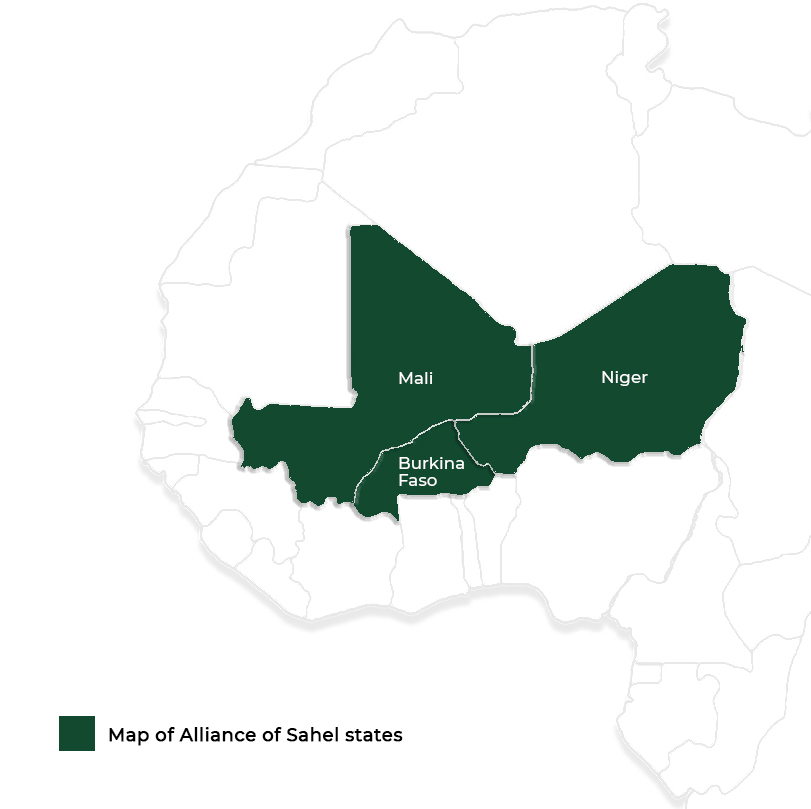

The fragmentation of the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) is no longer a theoretical concern but a stark reality. On January 29, 2025, despite a six-month extension offer from ECOWAS, the Alliance of Sahel States (AES)—Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger—formally withdrew from the Community, marking the most significant crisis in West Africa’s regional integration since the founding of ECOWAS in 1975. This second major rupture, after Mauritania’s exit in 2000, deals a significant blow to African regional integration and cooperation architecture.

Mauritania left primarily to pursue cultural and economic alignment with the Maghreb. However, weaker levels of economic, political and social connections with the wider ECOWAS members also played a role. The AES departure reflects a complex web of security concerns, geopolitical realignments and institutional failures. Despite the quarter-century gap, both exits share a common thread: dissatisfaction with ECOWAS’ capacity to address member-specific needs. However, the AES withdrawal poses more significant regional implications given these countries’ strategic position and collective emphasis on security cooperation to address the existential security threats facing them over economic integration.

The Sahel states’ exit from ECOWAS stems from a complex interplay of factors triggered by ECOWAS’ mishandling of the July 2023 Niger coup through swift, indiscriminate sanctions and military intervention threat—actions that revealed a disconnect between institutional responses and regional realities in the milieu of stalled governance reforms since 2015. This crisis exposed deeper issues: ECOWAS’ ineffectiveness in addressing terrorism and insurgency in the Sahel, economic marginalisation concerns, particularly regarding the CFA franc, and sovereignty issues over perceived French and Western influence in ECOWAS decision-making. Russia’s growing regional influence has provided these countries with alternative partnership options, reducing their dependence on traditional Western alliances and arguably accelerating their exit plans.

The rift also exposed ECOWAS’ fundamental flaws: over-reliance on sanctions without adequate diplomatic engagement, ineffective handling of political transitions and security challenges, and poor communication with affected populations. These missteps reveal an uncomfortable truth: the organisation’s traditional tools of influence—sanctions, isolation, and military threats—have become counterproductive, in a context that demands addressing legitimate issues and given that member states have alternative diplomatic and security options. Furthermore, ECOWAS’ limited recognition of changing geopolitical dynamics in the Sahel and insufficient engagement with civic stakeholders has undermined its credibility and legitimacy.

The implications of the coming into effect of the exit of the AES on 19 January have major consequences not just for the countries and ECOWAS but for the wider African regional integration process. For AES states, the withdrawal affects cross-border trade, financial transactions, and the movement of people, posing significant challenges for its members. They face potential economic isolation and increased maritime access costs as landlocked nations. Additionally, they risk reduced foreign direct investment due to perceived instability and limited market access. The announcements that they have made on establishing their own regional confederation and a 5-000-strong force suggest that these countries need to invest in building from scratch alternative frameworks for regional cooperation, particularly in areas previously covered by ECOWAS protocols—trade facilitation and security cooperation.

The withdrawal also carries significant implications for ECOWAS coastal states. The immediate impact includes the potential disruption of established trade routes and economic zones. Port cities and transit trade could experience an economic downturn. In contrast, cross-border communities and traditional trade networks may face challenges, given that Mauritania and Morocco are enhancing Sahel-Saharan integration and facilitating AES access to the Atlantic Ocean. From a security perspective as well, these states now face increased security vulnerabilities due to weakened regional cooperation mechanisms. The situation could also exacerbate illegal migration and trafficking, creating new security challenges.

Institutionally, it has also dented ECOWAS’ institutional credibility and regional integration vision, which has guided West Africa for nearly half a century. It also represents a loss of its collective bargaining power. This may weaken its position within the AU and broadly in international negotiations. Beyond weakening its position as a model for African regional integration and affecting international partnerships, the organisation faces reduced financial contributions and diminished influence.

The ECOWAS split poses profound implications for the African Union’s (AU) broader integration agenda, challenging current realities and future assumptions. As a precedent for regional bloc fragmentation, it calls into question the AU’s fundamental principle of regional integration as a pathway to continental unity. Furthermore, it presents significant risks to the African Peace and Security Architecture (APSA), in which ECOWAS is a crucial pillar. The emergence of alternative groupings like the AES signals a shift towards fluid, issue-based regional cooperation rather than strictly geographical arrangements. This suggests security concerns take precedence over economic considerations in shaping regional alignments. This development could impact the implementation of the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) and influence other sub-regional mechanisms, critically questioning the viability of regional economic communities as building blocks for continental unity. The 37th Ordinary Session of the AU Assembly in February 2024 expressed ‘grave concern of (sic) the joint communiqué of Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger withdrawing from ECOWAS’ and called on the AES countries to reconsider their decision and engage in Dialogue with ECOWAS in the spirit of Africa’s integration agenda consistent with AU Agenda 2063. The fact that there was no follow up on this and the AU did not initiate any robust facilitation between the two sides was a missed opportunity.

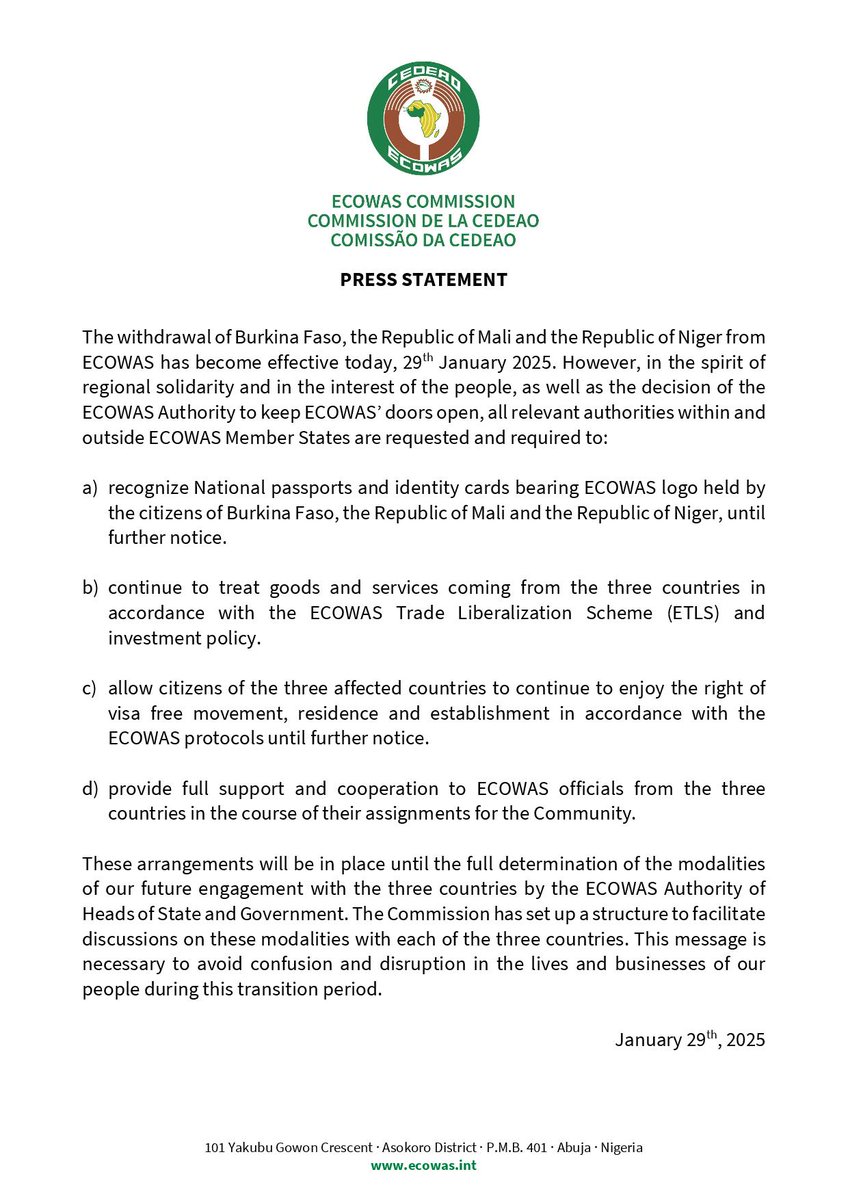

Despite the major setback the withdrawal represents, ECOWAS’s measured and pragmatic announcement on the day the exit of the AES countries came into effect on 29 January offers the basis for building bridges with the AEC countries. ECOWAS has established transitional arrangements preserving crucial privileges for citizens of these countries, including recognition of ECOWAS-branded documents, trade benefits under ETLS, visa-free movement rights, and support for ECOWAS officials from these nations. This balanced approach, which marks a departure from how ECOWAS handled the coup in Niger, aims to maintain diplomatic channels while protecting citizens’ and businesses’ interests. ECOWAS has chosen to keep its “doors open” while setting up structures for future engagement.

Yet, while ECOWAS’ transitional arrangements endeavour to minimise disruption, they do not address underlying issues or bridge the growing divide between Sahel states and coastal Guinea countries. Their withdrawal underscores the need to re-evaluate regional frameworks to better address Sahel’s unique challenges and update the instruments and mechanisms of regional cooperation at both the ECOWAS and AU levels.

The content of this article does not represent the views of Amani Africa and reflect only the personal views of the authors who contribute to ‘Ideas Indaba’