The Peace and Security Council in 2023: The Year in Review

Amani Africa

Date | 16 February 2024

WHAT THIS REVIEW IS ABOUT AND WHY

How did the African Union (AU) Peace and Security Council (PSC), Africa’s premier peace and security decision-making body, fare in delivering on its mandate in the face of the prevailing peace and security challenges on the continent during the just concluded year? What are the salient features of PSC’s role in the maintenance of peace and security in Africa in 2023? These and related questions are the focus of our annual review of the PSC which presents analysis on the work of the PSC in 2023. As in the previous years, this year’s review draws on the data and research work we carried out on the PSC in 2023.

2024 ELECTIONS OF THE MEMBERS OF THE AFRICAN UNION PEACE AND SECURITY COUNCIL: OVERVIEW OF THE PROCESS AND CANDIDATES

2024 ELECTIONS OF THE MEMBERS OF THE AFRICAN UNION PEACE AND SECURITY COUNCIL: OVERVIEW OF THE PROCESS AND CANDIDATES

Date | 12 February 2024

The 44th ordinary session of the Executive Council will hold the elections of the ten members of the Peace and Security Council. Our policy brief has all that you need to know about the 2024 PSC elections and how and why they matter.

Health security and the promotion of peace and security in Africa

Health security and the promotion of peace and security in Africa

Date | 7 February 2024

Tomorrow (8 February), the African Union (AU) Peace and Security Council (PSC) will convene its 1200th session to deliberate on the theme of ‘health security and the promotion of peace and security in the continent’.

The session is expected to commence with opening remarks by Mohammed Arrouchi, the Permanent Representative of Kingdom of Morocco and Chairperson of PSC for the month of February. The AU Commissioner for Political Affairs, Peace and Security (PAPS), Bankole Adeoye, and the Commissioner for Health, Humanitarian Affairs and Social Development, Minata SAMATE CESSOUMA, as well as the Director-General of the Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (Africa CDC), Dr. Jean Kaseya, are expected to deliver statements. The African Commission on Nuclear Energy (AFCONE), the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) and Pateur Institute of Morocco are also expected to participate in this session.

This session comes amid a cholera outbreak gripping the Southern Africa region, which highlights the persisting challenges of disease epidemics facing the continent. According to Africa CDC, from January 2023 to January 24, 2004, a staggering total of 252,934 cases and 4,187 deaths have been reported from 19 AU Member States. Alarmingly, over 72.5% of these cases are reported from the Southern Africa Development Community (SADC) region. In response to the crisis, SADC convened an extraordinary summit on 2 February, during which the regional bloc outlined range of measures to curb the outbreak. While the session provides an opportunity to explore ways of supporting SADC’s efforts to address the outbreak, it also underscores the growing recognition of the need for a holistic approach that properly caters to human security.

The PSC has previously deliberated on various aspects concerning the nexus of health, peace and security, within the framework of its mandate under Articles 6 and 7 of the PSC Protocol, which outline humanitarian action and disaster management as integral powers and functions of the PSC. Article 15(1) of its Protocol also stipulate that the PSC shall take active part in coordinating and conducting humanitarian action in the event of conflicts or natural disasters, while Article 13(f) specifically mandates the African Standby Force (ASF) to engage in humanitarian assistance to alleviate the suffering of civilian population in conflict areas and supporting efforts to address major natural disasters. Among its significant decisions in fulfilling this mandate was the authorization of an AU-led military and civilian humanitarian mission during its 450th session in August 2014 in response to the West Africa Ebola Virus Disease outbreak.

At its 742nd session held in January 2018, PSC recognized that disease epidemics are increasingly pausing serious social, economic, political and security threat to many parts of the continent, while emphasizing the imperative of mainstreaming Africa’s public health security within the overall framework of the AU Peace and Security Architecture. It also underscored the need for Member States to embrace and further enhance their collective security approaches and cooperation in preventing, controlling and combating disease epidemics. In the wake of the COVID-19 outbreak, PSC also convened several sessions to explore and address its impact on the peace and security in the continent. Notably, PSC’s 918th session, held in April 2020, acknowledged that ‘COVID-19 constitutes an existential serious threat to international peace and security’, further recognizing the ‘very serious and unprecedented threats to human security and national economies’ posed by the pandemic.

Over the years, AU has initiated different institutions and strategies to address the health related challenges of the continent. Aspiration 1 of Agenda 2063, Africa’s blueprint and master plan for transforming Africa into the global powerhouse of the future, envisions a prosperous Africa based on inclusive growth and sustainable development. One of the key goals for Africa to realize this aspiration is to ensure that its citizens are healthy and well-nourished and adequate levels of investment are made to expand access to quality health care services for all people. AU also developed the African Health Strategy 2007-2015 and 2016-2030. In January 2017, the Africa Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Africa CDC) was launched to support public health initiatives of Member States and strengthen the capacity of their public health institutions to detect, prevent, control and respond quickly and effectively to disease threats. In a significant move in February 2022, the Assembly (Assembly/AU/Dec. 835(XXXV)) elevated Africa CDC to an autonomous public health institution. It also upgraded the ‘AU COVID-19 Response Fund’ into the ‘Africa Epidemics Fund’ to mobilize resources for preparedness and response to disease threats on the continent. Furthermore, the Africa Medicine Agency (AMA) has been established as a specialized agency of the AU through a treaty adopted in February 2019 to enhance the capacity of State Parties and regional mechanisms to regulate and improve access to quality, safe and efficacious medicines, medical products and technologies in Africa.

While the initiative to enhance its health security architecture is commendable, the continent still faces recurring disease outbreaks, including emerging and re-emerging infectious diseases. The COVID-19 pandemic starkly exposed the ‘weaknesses and inequities’ inherent in the global health ecosystem, where Africa found itself largely neglected as wealthier nations monopolized doses for their own citizens and refused the request for TRIPS waiver to allow the generic production of COVID-19 vaccine. This underscores the critical imperative for Africa to prioritize investments in its health system and enhance its preparedness for future outbreaks. Indeed, it was against this context that the AU launched a framework for action known as ‘A New Public Health Order for Africa’ in September 2022 with the view to addressing the structural deficiencies ranging from national to global health system. The new public health order calls for: strengthened public health institutions, strengthened public health workforce, expanded manufacturing of health products, increased domestic investment in health, and action-oriented and respectful partnerships.

One key aspect of tomorrow’s deliberation is expected to be the intersection between health, peace and security. Echoing the sentiments of the Director-General of the World Health Organization (WHO), it is often stated that ‘there is no health without peace and no peace without health’, encapsulating the ideals of the WHO Constitution which recognizes that the health of all peoples is fundamental to the attainment of peace and security and is dependent on the fullest co-operation of individuals and states. The new WHO Global Health and Peace Initiative (GHPI), aimed at strengthening the WHO and health sector’s roles in fostering peace, highlights the intricate and bidirectional interplay between conflict, health and peace. The most apparent nexus between health and peace arises when conflicts precipitate direct, violent fatalities among civilians and combatants, leading to physical and psychological disabilities. Conflicts disrupt health systems, impede medical supply chains, break social structures, and cause health care workers to leave, and fuel epidemics and starvation.

On the other hand, as the GHPI notes, for citizens, the provision of healthcare and other essential services serves as the most tangible manifestation of national authority and a key determinant of state legitimacy. Disparities in the delivery of these services can erode such legitimacy and escalate the risk of violence, particularly when certain groups perceive unequal access as deliberate exclusion or neglect by the government. In some context, the lack of access to basic services, including health, has been identified as a driver for recruitment into violent extremist groups. Healthcare systems that address economic, geographic, epidemiological and cultural barriers to access, while striving for Universal Health Coverage (UHC), enhance better state-citizen relationships. This aspect of the intersection also underpins the concept of health security, an essential component of human security, as good health is not only vital for human survival but also plays crucial role in sustaining livelihoods and upholding human dignity.

In light of the above, there are several policy considerations that merit reflection in tomorrow’s deliberation. Beyond mere recognition of constitutional recognition, governments should demonstrate their commitment to the right to health through tangible actions, including through prioritizing and allocating adequate resources for healthcare. In April 2001, Member States of the AU committed to allocate at least 15% of their annual budgets to health, known as the ‘Abuja Declaration’. However, over two decades later, only a few countries (South Africa and Cape Verde, according to one source) have achieved that target. It is also imperative that health policies and their implementation be grounded in the principles of equity and universal access to high-quality care. Such an approach not only fosters inclusivity but also contributes to achieving sustainable peace. In fragile and conflict settings, targeted health interventions have a high potential to significantly enhance prospects for peace. These interventions are particularly effective when tailored to address the root causes, drivers, and triggers of conflict. Moreover, initiatives aimed at preventing the collapse of health systems and subsequent reconstruction play pivotal role in mitigating simmering grievances and preventing further tension fueled by inadequate access to healthcare.

The expected outcome of the session is a communiqué. PSC may take the opportunity to welcome the convening and outcome of the 2 February extraordinary summit of SADC on the cholera outbreak in the region. In this regard, PSC may call upon the Africa CDC and international partners to sustain their technical and financial support for the cholera response efforts in the region. Recognizing the nexus between health and peace, and health security as a fundamental pillar of human security, PSC may echo the statement by Director-General of the World Health Organization (WHO) that ‘there is no health without peace and no peace without health’. While highlighting the imperative of health security in fostering sustainable peace and development in the continent, PSC may urge Member States to demonstrate political commitment by increasing investments in the health sector and establishing equitable health system to attain universal health coverage. In this connection, PSC may seize the opportunity to reiterate the importance of Member States reaffirming their commitment to the Abuja Declaration, which calls for allocating 15% of their annual budget on health. In relation to Africa’s New Public Health Order, it may call upon various stakeholders, including Member States, international partners, the private sector, Civil Societies to support the full implementation of the initiative and enhance health emergency preparedness and response. It may also underscore the significance of investing in vaccine production, as well as the imperative to protect health infrastructure and personnel. Finally, PSC may urge the Commission to work on the full operationalization of the different initiatives that are aimed at strengthening AU’s health security architecture, notably Africa CDC, the Africa Medicine Agency (AMA), and Africa Epidemics Fund.

Monthly Digest on The African Union Peace And Security Council - December 2023

Monthly Digest on The African Union Peace And Security Council - December 2023

Date | December 2023

In December, under the chairship of the Gambia, the African Union (AU) Peace and Security Council (PSC) had a scheduled program of work consisting of two sessions, the annual retreat with the African Peer Review Mechanism (APRM), the annual high-level seminar and an informal consultation. Additionally, the PSC held a consultation to discuss the draft UN Resolution on Financing of Peace Support Operations.

Discussion on Transitional Justice and Post-Conflict Peacebuilding

Discussion on Transitional Justice and Post-Conflict Peacebuilding

Date | 5 February 2024

Tomorrow (6 February) the African Union (AU) Peace and Security Council (PSC) will convene its 1199th Session. This session will consider transitional justice and post-conflict peacebuilding.

The session is expected to begin with opening remarks by Mohammed Arrouchi, the Permanent Representative of Kingdom of Morocco and Chairperson of PSC for the month of February. This will be followed by a presentation of the AU Transitional Justice Policy by Bankole Adeoye, the AU Commissioner for Political Affairs, Peace and Security (PAPS). Statement is also expected to be delivered by the African Commission on Human and People’s Rights. Representatives of the National Human Rights Council of Morocco and the EU Delegation to the AU are also respectively expected to make statements.

Since the adoption of the AU Transitional Justice Policy (AUTJP) in 2019, the PSC has only convened once to discuss the AUTJP on 23 August 2022. The 1102nd session, focused on the deliberation of the AUTJP, aimed at allowing AU Member States to exchange their experiences, best practices, challenges, and prospects in the implementation of the policy. Additionally, it aimed to explore ways of better addressing the underlying causes of conflict and insecurities and foster synergies that can have a multiplied impact. It is also recalled that the 1102nd session decided to regularize briefing on the theme as an annual meeting of the Council.

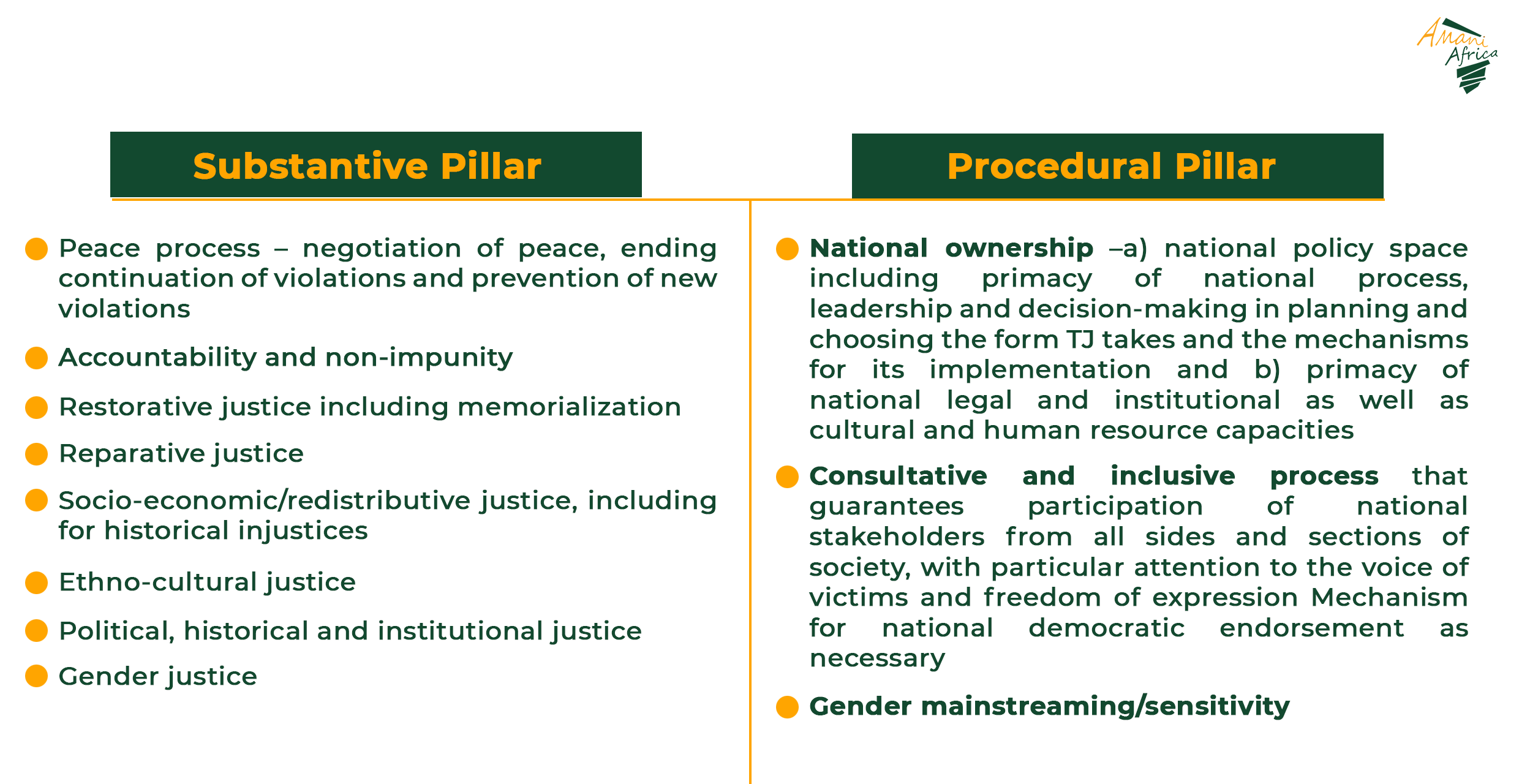

Facts on the AU Transitional Justice Policy (TJP)

Although there were no specific sessions dedicated to transitional justice and post-conflict peacebuilding, the Council held various sessions to identify policy options for transitional justice initiatives and discussed different transnational justice mechanisms. Under the theme ‘peace, reconciliation and justice’, the PSC conducted several discussions. Notably, during the 16th Extraordinary Session of the AU Assembly in May 2022 in Malabo, Equatorial Guinea, the focus was on terrorism and unconstitutional changes of government in Africa. It was during this session that 31 January of each year was designated as the ‘Africa Day of Peace and Reconciliation’. Moreover, in its 525th session in July 2015, the PSC agreed to include the theme ‘Peace, Reconciliation, and Justice’ as a regular item on its annual program of activities. Lastly, during its 899th session on 5 December 2019, the PSC agreed to dedicate an annual session to sharing experiences and learning lessons related to national reconciliation, peace restoration, and cohesion building in Africa.

As indicated in the Concept note prepared for the session, tomorrow’s session will serve as an opportunity for the PSC to receive an update in the implementation of the AUTJP. In ensuring the effective implementation of the policy, the Roadmap for the Implementation of the AUTJP outlines various activity areas to be implemented by the AU Commission. One of the key activities is resource mobilisation in support of the implementation of the policy. In this regard, during its 1102nd session, the PSC requested the Chairperson of the AU Commission to mobilize the necessary resources for the successful implementation of the AUTJP.

In response to this request and in alignment with the roadmap, the AU and EU have launched the Initiative for Transitional Justice in Africa (ITJA) project. This three-year project, officially launched on 25 October 2023, aims to support AU member states in adopting the AUTJP and implementing transitional justice processes at the national level. The ITJA project will be executed by a consortium of three organisations, with the International Center for Transitional Justice (ICTJ) leading the initiative, despite the existence of African institutions that could play a leading role in the development of the AUTJP, most notably the Centre for the Study of Reconciliation and Violence (CSVR). The African Transitional Justice Legacy Fund (ATJLF) and the Centre for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation (CSVR) are also part of the consortium. This initiative covers various activities outlined in the implementation roadmap, including awareness creation and popularising the AUTJP, technical assistance to AU Member States and commissioning research on transnational justice in Africa. Most importantly, the initiative assists in the establishment and coordination of the African Women Platform on Transitional Justice and increases the meaningful participation of civil society organisations in the design, implementation, and monitoring of transitional justice mechanisms by strengthening its capacity. In this regard, it is expected that the AU Commission will brief the Council on how these activities are planned to be undertaken by the consortium.

“The ITJA project will be executed by a consortium of three organisations, with the International Center for Transitional Justice (ICTJ) leading the initiative, despite the existence of African institutions that could play a leading role in the development of the AUTJP, most notably the Centre for the Study of Reconciliation and Violence (CSVR). “

Furthermore, the AU Commission is also expected to emphasize its efforts in implementing the AUTJP in relation to capacity building. In this regard, the Commission is likely to discuss various capacity-building training activities offered to youth and women. These include providing training on the application of the Policy to The Gambia, Ghana, Zimbabwe and South Sudan.

In exploring the challenges, the PSC may emphasise that the successful implementation of transitional justice in Africa hinges on addressing key challenges. The success of transitional justice endeavours is intricately tied to the political commitment, leadership, mobilization of support for and confidence in the process from a critical mass of the public and the capacity of the country concerned. Political buy-in along with a level of public support for and confidence in the process remains a crucial determinant of the success of transnational justice.

Even when political buy-in exists, capacity limitations may get in the way of implementing the AUTJP. The AU’s capacity to provide assistance is intricately linked to the financial resources at its disposal. One viable solution that the Council could explore to overcome this financial challenge involves the exploration of alternative sources of funding identified in the revised AU PCRD policy considering the critical contribution of transitional justice mechanisms, including truth and reconciliation processes for post-conflict peacebuilding. Additionally, lack of public awareness and active participation in the transitional justice process may also be raised as a factor that could hinder the success of the transitional justice process. Some of the key considerations for addressing technical and public awareness challenges could be the establishment of a continental network of transitional justice practitioners and analysts as an important platform for providing timely and relevant technical support for the implementation of the AUTJP in member states and the institutionalisation of the continental forum on transitional justice into the annual indicative program of the PSC.

“Some of the key considerations for addressing technical and public awareness challenges could be the establishment of a continental network of transitional justice practitioners and analysts as an important platform for providing timely and relevant technical support for the implementation of the AUTJP in member states and the institutionalisation of the continental forum on transitional justice into the annual indicative program of the PSC. “

In relation to countries that are undergoing political transition, the absence of a comprehensive legal framework or supportive legislation can impede the successful implementation of transitional justice. Moreover, in regions facing ongoing or latent conflict, security concerns can pose a significant challenge to the implementation of transitional justice.

Another aspect of the session is expected to be the sharing of experiences and challenges in the implementation of the AUTJP, particularly in relation to the development and implementation of transnational justice programs. There are various AU member states that are resorting to the use of transitional justice as a means of resolving grievances that resulted from conflicts. A recent example of this aspect is Ethiopia. The peace deal that was signed in November 2022 between the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia (FDRE) and the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) envisaged that ‘the government of Ethiopia shall implement a comprehensive national transitional justice policy aimed at accountability, ascertaining the truth, redress for victims, reconciliation and healing consistent with the constitution of the FDRE and the African Union Transitional Justice Policy Framework’. In March 2023, the AU announced that it will pledge to provide support to the planned transnational process in Ethiopia. Therefore, it is anticipated that the PSC will receive an update on the contribution of the AU towards the development of the transitional justice policy in Ethiopia and the extent to which the AUTJP has been used to inform and shape Ethiopia’s policy.

The AU is also assisting South Sudan’s transitional justice and post-conflict peace-building efforts. The revitalized Agreement for Resolution of Conflict in South Sudan (R-ARCSS) signed in 2018 provides for transitional justice, reconciliation and healing (Chapter 5). Under the R-ARCSS, the parties committed to the establishment of three transitional justice mechanisms: Hybrid Court, the Commission for Truth Reconciliation and Healing (CTRH) and the Compensation and Reparations Authority (CRA). The AU collaborated with the Government of South Sudan in convening a transitional justice conference in May 2023 in support of the process towards the adoption of the relevant legal instruments for the operationalization of the transitional justice mechanisms under Chapter V of the agreement. Despite the failure to meet the deadline for the operationalization of these mechanisms, there are recent developments highlighted in the report of the Reconstituted Joint Monitoring and Evaluation Commission (RJMEC). The report stated that CTRH and CRA Bills was adopted by the Council of Misters and they are expected to be enacted by the parliament. Yet, there is no progress regarding the hybrid court.

The expected outcome is a communique. The PSC may encourage the developments made regarding resource mobilization and advocate for sustained efforts in resource mobilization to support the effective implementation of the African Union Transitional Justice Policy (AUTJP). Additionally, the PSC may applaud and reinforce support for the AU-EU Initiative for Transitional Justice in Africa (ITJA) project and encourage enhanced use of the technical expertise present in African institutions that played a leading role in the development of this globally most up-to-date policy on transitional justice and post-conflict peacebuilding. It may underscore the need to strengthen efforts to raise awareness and popularize the AUTJP across Member States. The PSC may in this respect call for the establishment of a continental network of transitional justice practitioners and analysts as an important platform for providing timely and relevant technical support for the implementation of the AUTJP in member states. The Council may also request the establishment of a regular monitoring and evaluation mechanism for AUTJP implementation progress. In recognising the important role of civil society organisations, particularly women and youth-led organisations, the Council may emphasise the need for increased collaboration with civil society organisations, empowering them to actively participate in the design, implementation, and monitoring of transitional justice mechanisms. Furthermore, the PSC may reiterate the need for regular updates on the experiences and challenges faced by AU Member States in implementing the AUTJP and facilitating knowledge-sharing sessions to derive best practices and lessons learned from countries undergoing transitional justice processes. To this end, the PSC may decide to institutionalise the continental forum on transitional justice that the AU Commission organises annually as part of its calendar of events in its annual indicative program.