Annual Activity Report of Amani Africa 2024

Annual Activity Report of Amani Africa 2024

HIGHLIGHTS OF THE YEAR

In 2024, Amani Africa has continued to consolidate its policy work and impact, strengthening its role in knowledge production, policy analysis, the timely dissemination of critical information on AU affairs, including on the Peace and Security Council, convening of policy forum and training, provision of technical support and strategic communications and outreach.

During the year, we broadened both the range of issues covered and the diversity of our outputs, enhancing their reach, relevance and influence. Additionally, we introduced new initiatives such as Amani Africa’s new podcast, The Pan-Africanist, and production of factsheets on key AU policy events, with a particular focus on developments from the AU Summit.

75th Anniversary of the Geneva Conventions: Preserving Our Common Humanity in a Time of Major Crises of Compliance

75th Anniversary of the Geneva Conventions: Preserving Our Common Humanity in a Time of Major Crises of Compliance

Date | 7 April 2025

INTRODUCTION

2024 marked the 75th anniversary of the Geneva Conventions(GCs) of 1949. On 16 September 2024, the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) Delegation to the African Union (AU) and the Swiss Mission in Addis Ababa, convened a high-level event to commemorate the anniversary. This policy brief, produced within the framework of our partnership with the ICRC Delegation to the AU, presents an analysis of the major themes and insights that emerged from the commemoration event.

The first section of the policy brief provides a synthesis of the main insights into the achievements of the Geneva Conventions and why they remain vital today. Considering the various significant global developments, the second section identifies the existing and emerging challenges facing the Conventions and IHL in general. The third section draws the lessons and insights from experiences shared during the event. In part four, the policy brief explores the key role of various stakeholders in reaffirming the continued importance of IHL. Finally, it concludes with key messages and recommendations.

Implications of the AU Commission leadership elections for the AU’s standing and role

Implications of the AU Commission leadership elections for the AU’s standing and role

Date | 4 April 2025

Tefesehet Hailu

Researcher, Amani Africa

The elections of the African Union (AU) Commission leadership held during the 38th Ordinary Session of the AU Assembly that took place from 12 to 16 February 2025 could mark a turning point for the continental organisation. While they reveal strains in the state of intra-African cohesion and procedural gaps and complexities, what makes the elections of the AU Commission leadership remarkable is the timing of the elections. The elections were held, and the new AU Commission leadership was constituted at a time when major challenges and changes are unfolding both in Africa and globally, bringing Africa and the continental body to a crossroads.

Economic pressures, including soaring debt levels, a worsening cost-of-living crisis, and punishingly expensive cost of access to development finance, are eroding some of the gains made in recent decades as millions of people are pushed into extreme poverty. Meanwhile, conflicts are reaching unprecedented levels in both scale and geographic spread, further destabilising the continent as outlined in two major Amani Africa research reports (here and here), making the AU appear helpless and irrelevant. Efforts toward regional integration are also facing setbacks, exemplified by rising inter-state tensions and the recent withdrawal of the three Sahel countries from ECOWAS, exemplifying a fragmentation of regional blocs threatening the AU’s foundation. While demand for a democratic and accountable system of governance continues to rise and several countries show electoral democratic resilience in the face of challenges, democratic governance and constitutional rule remain under strain, with disputed elections and a resurgence of military coups threatening stability. At the same time, the global order is shifting, marked by the rise of multipolarity, rising geopolitical tensions, rapid technological advancements, and a dismembering and failing multilateral system.

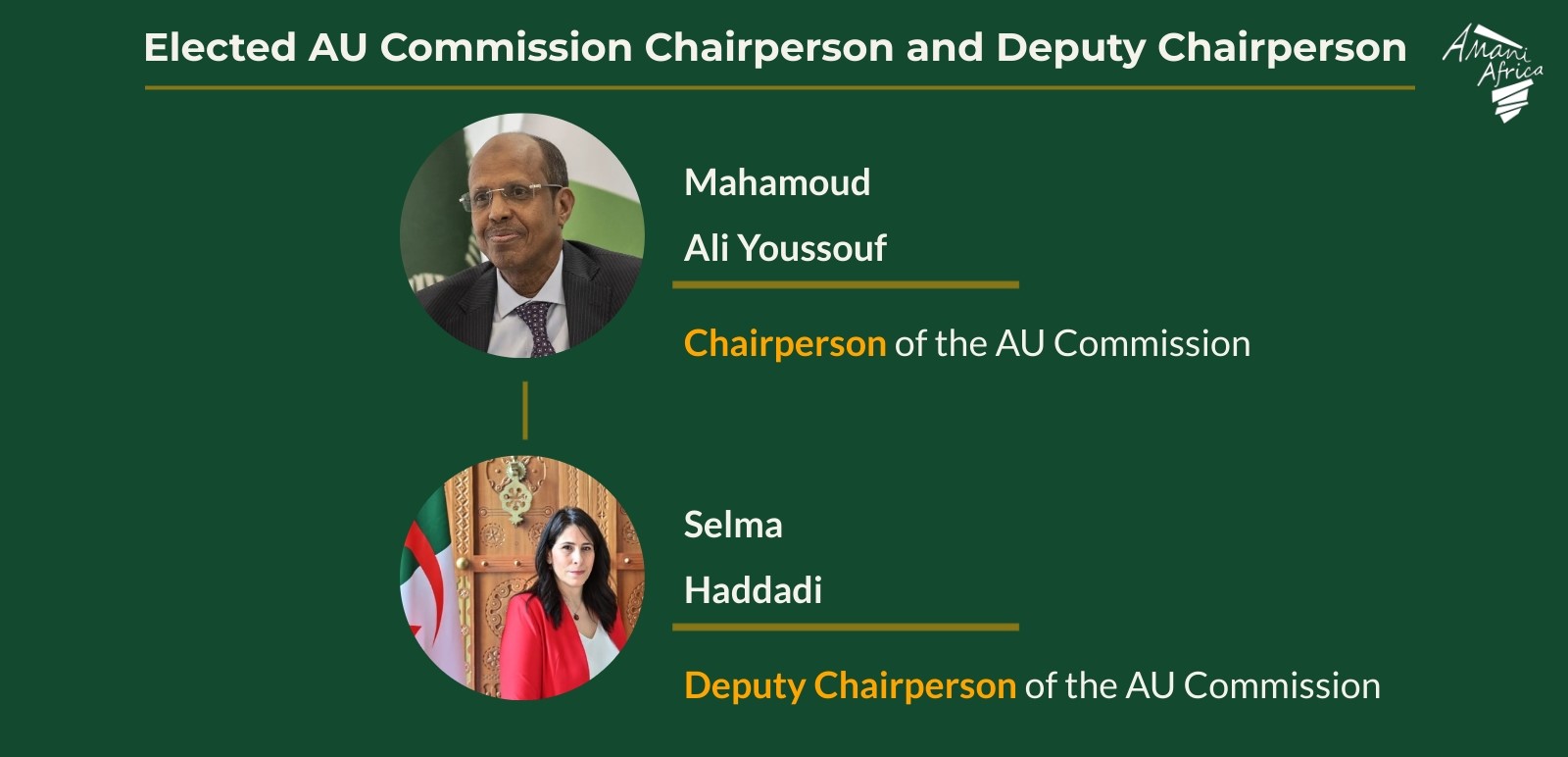

As per the decision of the 22nd extraordinary session of the AU Executive Council, which decided the election to be based on the principle of inter-regional rotation, the Eastern region is to submit candidates for the role of Chairperson, and the Northern region is to submit candidates for the role of Deputy Chairperson. As a result, while the eastern region submitted three candidates from Djibouti, Kenya, and Madagascar for the chairperson positions, the Northern region submitted six candidates from Algeria, Egypt, Libya and Morocco.

The three candidates listed for the position of Chairperson were Raila Odinga, Former Prime Minister of Kenya; Mahamoud Ali Youssouf, Foreign Minister of Djibouti; and Richard Randriamandrato, Former Foreign Minister of Madagascar. Despite having three candidates in the race, the main contenders were Mahamoud Ali Youssouf and Raila Odinga.

Mahmoud Ali Youssouf steadily gained votes across all seven rounds, increasing from 18 votes in Round 1 to 33 votes in Round 7. His main competitor, Raila Odinga, maintained a relatively stable vote count, starting with 20 votes in Round 1 and ending with 22 votes in Round 6, failing to expand his support base. Meanwhile, Richard J. Randriamandrato experienced a sharp decline, dropping from 10 votes in Round 1 to just 5 votes by Round 3, after which he was eliminated. This suggests that he had limited backing, and his supporters likely shifted to other candidates, primarily Mahmoud Ali Youssouf, contributing to him assuming a lead during subsequent rounds.

Interestingly, abstentions remained low in the early rounds (one vote per round) but surged to 14 in the final round. This spike suggests that some member states either refused to back the remaining candidate, Mahmoud Ali Youssouf, or preferred to abstain once their favored candidates had been eliminated. The significant increase in abstentions also indicates that some member states may have sought to postpone the election. If that had happened, the Assembly might have followed the precedent of suspending the entire election as it did in 2016.

Before the election, it is recalled that the Southern African Development Community (SADC) urged its 16 member states to support Madagascar’s candidate, Richard Randriamandrato, in a last-minute letter published on February 12, 2025. The timing of the endorsement, just days before the election, suggests a last-minute push to consolidate regional votes, potentially influencing undecided member states. One can assess that the last-minute lobbying efforts have failed, but they were also decisive in shaping the final outcome of the elections.

When it comes to the election for the Deputy Chairperson position, the voting pattern reveals a competitive race primarily between Salma Malika Haddadi of Algeria and Latifa Akharbach of Morocco, with Hanan Morsi, despite appearing to be one of the favorites, failing to secure more than six votes and being eliminated early. Haddadi gained steady support across all rounds, starting with 21 votes in Round 1 and reaching 33 votes in Round 7, indicating strong and consistent backing from her supporters. In contrast, Akharbach experienced fluctuations, initially securing 21 votes but dropping to 18 in Round 2 before stabilising at 22 votes from Round 3 to Round 6.

In the election for the position of Deputy Chairperson, a notable trend during the various rounds of elections was the fact that the candidate Selma Hadadi maintained a lead position, thereby becoming the only candidate on the ballot after the sixth round. The most decisive moment came in Round 7 when Haddadi reached 33 votes, suggesting a shift of support from eliminated candidates and a strategic realignment among member states. However, similar to the election for the chairperson position, at the 7th round, there were 13 abstentions. This highlights the existence of a fault line in inter-state relations within the AU, which pits Algeria against Morocco, a fault line that threatens AU processes to be held hostage to regional tensions.

These elections underscore the intricate interplay of regional allegiances, strategic maneuvering, and procedural challenges within the AU. While candidates like Youssouf and Haddadi demonstrated the required 2/3rd majority support from AU member states, the struggle to get a two-thirds majority vote and the surge in abstentions reflect deeper divisions. These divisions could get in the way of pursuing the objectives of the AU as set out in the Constitutive Act and defending the interests of the continent. Accordingly, apart from adopting urgent strategic steps for arresting the spread and intensifying conflicts on the continent, mending these divisions for building a minimum level of consensus among AU member states is one of the most immediate pressing tasks for the new leadership.

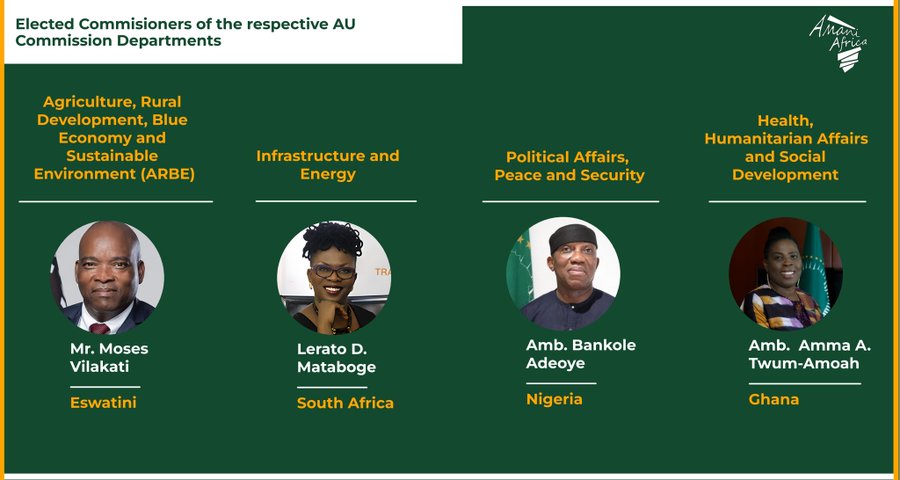

With regards to the elections of the Commissioners, with East Africa and North Africa already occupying the Chairperson and Deputy Chairperson roles, candidates for the six commissioner positions were submitted from the Central, West and Southern Africa regions. However, only four of these positions were successfully filled: Agriculture, Rural Development, Blue Economy, and Sustainable Environment (ARBE); Health, Humanitarian Affairs, and Social Development (HHS); Infrastructure and Energy; and Political Affairs, Peace, and Security (PAPS). Notably, the positions for Commissioner for Economic Development, Trade, Tourism, Industry, and Mining, as well as Education, Science, Technology, and Innovation, remained vacant due to a combination of scoring requirements and regional representation rules.

The position for the Commissioner for Economic Development, Trade, Tourism, Industry, and Mining was not filled because none of the seven candidates from the Southern and Central regions met the minimum threshold of 70%.

The election for the Commissioner for Education, Science, Technology, and Innovation also faced hurdles. Out of twelve candidates shortlisted by the High-Level Panel of Eminent Africans, only one candidate from the Southern region achieved a Category A ranking, scoring 90% or above. However, this candidate was ultimately eliminated after the position for Commissioner of Agriculture, Rural Development, Blue Economy, and Sustainable Environment was filled by another candidate from the same region. This decision was as per the Revised Statute of the AU, which prioritises regional diversity and gender balance. Specifically, the two commissioner positions allocated to a single region must be occupied by one male and one female, preventing both roles from being held by candidates of the same sex. As such, since the ARBE portfolio was filled by a male candidate, the Southern region could not secure another position, leading to the elimination of the highly qualified candidate for Education, Science, Technology, and Innovation.

The result was that the two portfolios would be filled from the Central African region during the election set to take place during the extraordinary session of the Executive Council set for 15 April 2025. It is now reported that none of the candidates in the list of candidates from the Central Region submitted to fill in the two commissioner positions managed to meet the minimum requirements. This means that the two positions may end up being vacant for an extended period of time, with the potential risk of affecting AU’s participation in the G20 as the position of AU Sherpa remains unfilled.

The alphabetical order of the elections has further influenced the process. For instance, the election for the Commissioner of Health, Humanitarian Affairs, and Social Development was impacted by the prior filling of the two allocated positions for the Southern region. Initially, there were two candidates in contention: one from the Western region and one from the Southern region. However, by the time the election for this position took place, the Southern region had already filled its quota, leaving the Western region candidate as the sole viable option. This procedural nuance highlights how the sequencing of elections can significantly influence outcomes, often sidelining qualified candidates due to regional constraints.

The process of elections for the position of Commissioners revealed both the strengths and limitations of the AU’s commitment to regional representation and gender balance. While these principles are laudable, their implementation can sometimes result in unintended consequences, such as the inability to fill critical positions or the exclusion of highly qualified candidates. Moving forward, the AU may need to revisit its election procedures to strike a better balance between representation and meritocracy, ensuring that its leadership remains both diverse and highly capable.

Additionally, as pointed out by the Panel of Eminent Persons reviewing the qualifications of candidates, the process for the submission of candidates shows that member states are failing to put forward candidates who possess the requisite competence and skills. It appears that political considerations often influence candidate selection, leading to the exclusion of highly qualified individuals. This limits meritocracy and narrows the talent pool, as the authorities handling the identification of candidates at the national level may prioritise loyalty and connections over competence.

It is clear that the AU Commission leadership elections reveal that the election process is still fraught with challenges that necessitate further refinement. Additionally, the elections of the new AU Commission leadership mark a pivotal moment for the continent, offering a unique opportunity to redefine the Union’s approach and mode of work. If this leadership transition breaks from the business-as-usual approach of the past years to the profound changes and challenges, it can enable Africa to fend off and minimise the adverse impacts of a world in a destabilising tumult. Most notably, it can reposition the AU for advancing Africa’s integration and development continentally and its collective voice globally by leveraging its immense potential, driven by the world’s youngest population, huge natural resources endowment and reserve of renewable energy, vast arable land and a growing middle class.

The content of this article does not represent the views of Amani Africa and reflect only the personal views of the authors who contribute to ‘Ideas Indaba’

Open Session on Hate Crimes and Fighting Genocidal Ideology in Africa & 31st Anniversary Commemoration of the Genocide against the Tutsi in Rwanda

Open Session on Hate Crimes and Fighting Genocidal Ideology in Africa & 31st Anniversary Commemoration of the Genocide against the Tutsi in Rwanda

Date | 1 April 2025

Tomorrow (2 April), the African Union (AU) Peace and Security Council (PSC) will convene its 1272nd session as an open session to deliberate on Hate Crimes and Fighting Genocidal Ideology in Africa. This session will also commemorate the 31st anniversary of the 1994 Genocide against the Tutsi in Rwanda.

The meeting will begin with opening remarks by Rebecca Amuge Otengo, Permanent Representative of the Republic of Uganda to the AU and stand-in Chair of the PSC for April 2025 followed by introductory remarks by Bankole Adeoye, AU Commissioner for Political Affairs, Peace and Security (PAPS). Presentations are expected from Adama Dieng, AU Special Envoy for the Prevention of Genocide and other Mass Atrocities, a Representative of the Republic of Rwanda and the Special Adviser of the UN Secretary-General on the Prevention of Genocide.

Tomorrow’s session is being convened in line with the PSC decision adopted at its 678th session held on 11 April 2017, in which it decided to convene annually in April a session on the prevention of hate ideology, genocide, and hate crimes in Africa. The session also forms part of the annual commemoration of the 1994 Genocide against the Tutsi in Rwanda.

The International Panel of Eminent Personalities, established by the Organization of African Unity (OAU) to investigate the 1994 Genocide, underscored in its report: ‘If there is anything worse than the genocide itself, it is the knowledge that it did not have to happen.’ The violence was made possible, among other things, by the failures of African and international actors to take preventive measures before the mass violence started or to halt it once it started. Cognizant of this, in its transition from the OAU to the AU, the continental body sought to move away from a dogmatic interpretation of non-interference, adopting the principle of non-indifference enshrined in Article 4(h) of the AU Constitutive Act. The memory of what happened in Rwanda and its meaning are inseparable from the raison d’etre for AU’s founding. This is also of direct concern for the PSC owing to the clear provision in the Protocol establishing it under Article 7, which enjoins the PSC ‘to anticipate and prevent disputes and conflicts, as well as policies that may lead to genocide and crimes against humanity.’ As such, one of the issues this commemoration raises for the PSC is how to safeguard the memory of this tragic catastrophe perpetrated at extraordinary scale and brutality for avoiding its recurrence anywhere in the continent as promised in Article 4(h) of the Constitutive Act of the AU.

The Council last convened on this subject during its 1206th session on 3 April 2024 during which the Council reiterated previous decisions it has made directing the AU Commission to provide comprehensive policy elaboration of hate speech and hate crimes, and compile adequate data to effectively deter, prevent and combat them. Other decisions from that session included a call for the Panel of the Wise to undertake a review of the status of implementation of the recommendations contained in the Report of the OAU International Panel of Eminent Personalities on the 1994 Rwanda Genocide and surrounding events, establishing effective accountability mechanisms, strengthening early warning systems, implementing preventive measures through education and public awareness, and addressing the role of digital spaces in exacerbating hate crimes.

Previous sessions have repeatedly called for the development of a comprehensive AU policy framework on hate speech and hate crimes, backed by data collection and preventive measures. Additionally, the establishment of an AU Human Rights Memorial to honor victims of atrocities, including the genocide against the Tutsi, apartheid, Ethiopia’s Red Terror, colonial oppression, and the transatlantic slave trade, remains an unfinished agenda. The AU’s Panel of the Wise has also yet to present the findings of its review on the status of recommendations from the OAU’s International Panel of Eminent Personalities.

Yet, the commemoration is not just about memory and honoring the lives of victims and survivors. Given its link to the commitment of the PSC protocol for respect for the sanctity of human life and IHL, it is of direct relevance for various conflict settings on the continent. As Adama Dieng, the AU Special Envoy on the Prevention of Genocide, noted during an address at the International Conference on Genocide Prevention in Kigali, ‘[t]he Constitutive Act of the African Union makes prevention a core part of its mission, yet we continue to witness rampant and widespread violations that challenge this commitment. The ongoing carnage in Sudan is a reminder of the painful cost inflicted on civilians when we fail to gather courage to trigger institutions and legal frameworks we painstakingly created to precisely address challenges of this nature.’

It came as no surprise that in heeding the lessons from that dark history Dieng issued a statement issued on 29 October 2024, albeit several months following his appointment, expressing deep concerns over escalating violence, including mass killings, summary executions, abductions, and sexual violence in the context of the war in Sudan, warning that the full scale of atrocities remains obscured due to a telecommunications blackout. As the second anniversary of the devastating conflict between the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) approaches on 15 April, a significant development in recognition of the widespread human rights violations has been the U.S. government’s determination that the RSF has committed acts of genocide. This makes it the second time in two decades that such determination of the occurrence of genocide was made in relation to Sudan. There are concerns of other forms of atrocities being perpetrated in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). The UN Human Rights Council in February 2025 adopted a resolution establishing a fact-finding mission on the Human Rights Situation in Eastern DRC, expressing condemning in ‘the strongest terms’ the persistence violations and abuses, ‘in particular conflict-related sexual violence and gender-based violence, summary executions, abductions, enforced disappearances, targeted attacks against human rights defenders, journalists, other civil society actors and peacekeepers, and the bombing of sites for displaced persons, hospitals and schools.’ Incidents of mass massacre in the context of conflicts involving terrorist groups in the Sahel show that issues of atrocities and violations of IHL are not limited to Sudan and Eastern DRC, underscoring the importance of this session and the role of the AU Special Envoy.

Following his official assumption of duty in June 2024, Dieng outlined his main task to identify risk indicators of the ideology of hate, genocide, and other mass atrocities; ensure timely interventions; enhance early warning mechanisms; pay more attention to early warning signs; prevent escalation; effectively regulate and closely monitor the misuse of media platforms and encourage Member States to adopt necessary policies that would monitor the media and promote professionalism, ethics and factual reporting; prevent the exploitation and propagation of extremist messages that incite hate crimes and genocide; and regularly brief the AUC Chairperson and AU Organs, particularly the PSC. In recent months, the Special Envoy has undertaken a series of engagements with various stakeholders in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Rwanda, and South Sudan.

It would therefore be of interest for members of the PSC to hear from Dieng on his assessment of the risks, on the steps that are needed to avert these risks or arrest the occurrence of mass atrocities in conflict settings where these are unfolding and to enhance prevention strategies to mass atrocities pursuant to Article 7 of the PSC Protocol. Equally important is ensuring that early warnings are effectively translated into early responses. Moreover, it is essential to establish an inclusive system of governance that represents all sectors of society and their interests.

It is to be recalled that the Council, at its 1147th session, called for the establishment of an African Centre for the Study of Genocide. Notable progress in this regard has been the announcement of the establishment of the African Center for Genocide Prevention (ACGP) as a regional institution at the International Conference on Genocide Prevention. The ACGP, headquartered in Rwanda, will focus on developing early warning systems to monitor and prevent genocidal threats, conducting research on prevention strategies and lessons learned, training policymakers to effectively combat genocide, and promoting grassroots reconciliation programs. Only second to the Johannesburg Holocaust and Genocide Centre on the continent with an explicit focus on genocide, the ACGP is expected to serve as a hub for research, education, and advocacy and foster dialogue among governments, civil society, researchers, and regional organisations.

The expected outcome of the session is a communiqué. The PSC may reiterate concern over the persistent spread of hate ideologies and genocidal rhetoric in Africa. It may welcome the progress being made around the establishment of the ACGP and the AU human rights memorial. The council may urge AU member states to sign, ratify, and implement the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide. It may encourage formal and informal education policies that foster social cohesion and the culture of human rights protection. The PSC may also call for enhanced collaboration with Regional Economic Communities (RECs) and Regional Mechanisms (RMs) to address the root causes of hate crimes and violent conflicts. The PSC may also welcome the appointment of the AU Special Envoy and may invite him to support the PSC in the implementation of its mandate under Articles 4(c) & (j) and 7 (1)(a) & (e), while expressing support for the initiatives he has taken since assuming office. It may also call on AU member states to investigate and prosecute individuals in their jurisdiction suspected of engaging in the perpetration of genocide, crimes against humanity and hate crimes and to put in place effective legislation for dealing with hate speech. It may also call on the AU to expedite the construction of the AU Human Rights Memorial.