Women, Peace, and Security in Africa

Women, Peace, and Security in Africa

Date | 20 March 2025

Tomorrow (21 March), the African Union (AU) Peace and Security Council (PSC) is scheduled to hold a session on the Women, Peace, and Security (WPS) agenda.

Following opening remarks by Mohammed Arrouchi, Morocco’s Permanent Representative to the AU and the stand-in Chairperson of the PSC for March 2025, Bankole Adeoye, AU Commissioner for Political Affairs, Peace, and Security (PAPS), will deliver the introductory statement. Bineta Diop, Special Envoy of the Chairperson of the AU commission on WPS, is expected to brief the Council on the progress made in the implementation of the WPS agenda. Presentations are also expected from representatives of the UN Women and the European Union Delegation to the AU. Nefertiti Mushiya Tshibanda, Permanent Representative of the International Organization of Francophone (OIF) and Nouzha Bouchareb, from the national chapter of the African Women’s Network for Conflict Prevention and Mediation (FemWise-Africa), are also expected to make interventions.

Since its 223rd session convened on 30 March 2010, when it decided to hold annual open sessions dedicated to the WPS theme, the PSC has institutionalised its session dedicated to the WPS agenda in Africa. And significant progress has been achieved normatively and in putting in place structures, processes and mechanisms for advancing the WPS agenda. As documented in our special research report, while significant normative advancements have been made, the persistent gap between policy commitments and implementation remains a major concern. As tomorrow’s session marks the 15th anniversary since the 223rd session of the PSC adopting the WPS agenda, a major issue for the PSC is how to advance implementation.

The last PSC session on the WPS agenda was on 30 October 2024 during the Council’s 1242nd session, marking the 24th anniversary of UNSCR 1325. The session underscored the critical role of women in conflict resolution and urged Member States to ensure a more equal representation of women in all aspects of peace processes, including the design and implementation phases. In the adopted communiqué, the Council made several requests to the Commission, including the establishment of rigorous monitoring and evaluation mechanisms for the implementation of Resolution 1325 and the exploration of funding options for gender components of peace and security, including from the Peace Fund.

Given the alarming levels of conflict-related sexual violence (CRSV) and gender-based violence (GBV) in conflict situations, including most notably in Sudan and Eastern DRC, one of the issues for the PSC is how to ensure that peace and security initiatives in specific conflict situations make provision for a gendered approach to peacemaking and mediation and for protection measures tailoring to the continuing vulnerability of women to CRSV and GBV. In this respect, a major new development that is expected to inform PSC’s consideration of how to enhance effective response to the persistence of CRSV and GBV in tomorrow’s session is the adoption by the 38th AU Assembly in February 2025 of the AU Convention on Ending Violence Against Women and Girls. This Convention is particularly significant in terms of the 2019 report of the Special Envoy noted in Amani Africa’s special research report that while there is some progress in respect to the provision of psychosocial protection and support, access to justice to ensure redress and accountability remains inaccessible for many women.

In this respect, it is of particular significance for members of the PSC to emphasise the need for speeding up the ratification of this newest AU Convention and its domestication as a pre-requisite for creating the legal, political and social conditions that promote respect for the physical security and dignity of women and girls. Equally, there is a need for the AU to take steps for adapting the measures envisaged in the Convention in order to ensure their integration into all peace and security initiatives of the AU and for designing tailored strategy for the Convention’s implementation in conflict situations. Apart from the prevention and response stages, the importance of the inclusion of gender-sensitive provisions into peace agreements to ensure that women’s security concerns are not sidelined in the post-conflict phase cannot be underestimated.

As this month marks 15 years since the introduction of the WPS agenda in the PSC, it is also of importance for members of the PSC to consider the effective operationalisation and implementation of various instruments developed over the years for advancing the agenda. One such agenda is the Continental Results Framework (CRF), a tool designed to institutionalise regular and systematic tracking of progress of the WPS agenda. The CRF is dependent on Member States’ willingness to adhere to reporting obligations and implement corrective measures. Even then, instead of making follow-up dependent exclusively on reporting by member states, members of the PSC may also consider the inclusion in the strategic plan of the Special Envoy on WPS of periodic assessment of both the performance of member states and all AU and Regional Economic Communities (RECs)/Regional Mechanisms (RMs) peace processes under the CRF.

FemWise Africa, a subsidiary body of the Panel of the Wise dedicated to advancing the role of women in preventive diplomacy and mediation, has played an important role in expanding the pool of women practitioners and experts and strengthening the role of women mediators and their contributions to more inclusive peace processes. Additionally, the decentralisation of FemWise-Africa is a critical step to facilitate localised interventions in preventive diplomacy and mediation. Still, the PSC must encourage Member States and RECs to accelerate efforts to establish national and regional chapters with adequate resources to ensure that women are involved in conflict prevention and mediation in meaningful ways.

Another issue expected to be raised in tomorrow’s session is the need to advance women’s meaningful participation in peace processes. The Conclusions of the high-level ministerial seminar, a biennial forum institutionalised as the Swakopmund Process, convened on 23 March 2024, underscored the importance of adopting a gender parity policy for all AU-led and co-led mediation processes. Despite being disproportionately affected by conflicts, women remain significantly underrepresented in decision-making roles. A gender parity policy would play a key role in ensuring that the selection and appointment of mediators, technical experts, special envoys and others relevant to the facilitation of peace processes takes into account gender perspectives and meaningful inclusion of women. However, despite growing commitments, women remain underrepresented, particularly in high-stakes mediation efforts. The significance of integrating women into peace processes, further to being a matter of justice, is also a matter of strategic imperative to ensure the durability of peace processes by leveraging women’s conflict-resolution skills and community engagement strengths for long-term stability.

It is in this respect that the PSC requested the AU Commission to develop a Policy Framework on Women Quotas in Formal Peace Processes across Africa. This framework aims to ensure that the continent meets the statutory minimum of 30% gender quota for women’s participation in all conflict prevention and management missions, peace processes, and election observation missions led by the AU. FemWise-Africa, in collaboration with the Gender, Peace, and Security Program and the Office of the Special Envoy on WPS, welcomed the PSC’s directive to develop a policy framework ensuring gender equity and equality in all AU-led mediation and peace processes. Tomorrow’s session thus presents an opportunity for the PSC to follow up on this request.

One of the challenges in the implementation of the WPS agenda is the lack of sustainable financing. It is to be recalled that in its 1187th session, the PSC emphasised the need for adopting financial mechanisms to facilitate the meaningful participation of women in peace processes, including capacity programs to provide the requisite skills in conflict prevention, resolution, and management. Financing WPS to support women’s leadership development, mediation training, and participation in peace missions is an essential component of ensuring women’s voices are meaningfully included. Tomorrow’s session may explore ways to mobilise additional resources to expand financial and institutional support for women-led mediation efforts.

The expected outcome of tomorrow’s session is a communique. The PSC is expected to strongly condemn conflict-related sexual violence (CRSV), especially against women and children in conflict situations, particularly in Sudan and Eastern DRC. The Council may express concern about the deteriorating security situation affecting women and girls in conflict-affected regions. The PSC may welcome the adoption of the AU Convention on Ending Violence Against Women and Girls and urge Member States to ratify and domesticate the Convention. The PSC may call on the relevant AU structures working on WPS to work jointly for adapting the measures envisaged in the AU Convention on Ending Violence Against Women and Girls in order to ensure their integration into all peace and security initiatives of the AU and for designing a tailored strategy for the Convention’s implementation in conflict situations. It may also call for a shift in the focus of the WPS agenda from the development of norms, structures and processes to implementation, including prioritisation of systematic integration of WPS across the conflict continuum from prevention to post-conflict. The PSC may request the inclusion into the strategic/work plan of the AU Special Envoy on WPS the conduct of a periodic assessment of both the performance of member states and all AU and RECs/RMs peace processes under the Continental Results Framework. The PSC may call for concrete measures on putting in place strategy for the implementation of the 30% quota for women participation in all peace processes at the AU, RECs/RMs and national levels. Council may also encourage Member States and RECs/RMs to accelerate efforts to establish national and regional chapters of FemWise with adequate resources to expand the pool of women peace experts and ensure participation of women.

Artificial Intelligence and its impact on peace, security and governance

Artificial Intelligence and its impact on peace, security and governance

Date | 19 March 2025

Tomorrow (20 March), the African Union (AU) Peace and Security Council (PSC) will convene its 1267th session on Artificial Intelligence (AI) and its impact on Peace, Security and Governance in Africa at the Ministerial level.

Following opening remarks by Nasser Bourita, Minister of Foreign Affairs, African Cooperation and Moroccan Expatriates and Stand-in Chairperson of the PSC for March 2025, Bankole Adeoye, Commissioner for Political Affairs, Peace and Security (PAPS), is expected to make an introductory statement. Lerato Mataboge, the AU Commissioner of Infrastructure and Energy, who is responsible for the file of technology, is expected to make a presentation. It is also expected that Bernardo Mariano Junior, Assistant Secretary-general, Chief Information Technology Officer, UN Office of Information and Communications Technology (UNOICT).

The PSC held its first session on Artificial Intelligence (AI) and its impact on peace and security in Africa during its 1214th session on 13 June 2024 as part of its 20th-anniversary commemorations. The session underscored AI’s transformative potential for peacebuilding, including its applications in early warning systems, conflict prevention, and post-conflict recovery. Most notably, however, it recognised the risks associated with its rapid development in a regulatory vacuum. Speaking at a recent United Nations Security Council (UNSC) meeting, UN Secretary-General António Guterres remarked, ‘Artificial intelligence has moved at breakneck speed. It is not just reshaping our world; it is revolutionising it. This rapid growth is outpacing our ability to govern it, raising fundamental questions about accountability, equality, safety, and security.’ Indeed, AI is reshaping the global security environment, with profound implications for governance, stability, and conflict dynamics.

The interest of the PSC in engaging with AI highlights its growing significance in Africa’s peace and security landscape. In Africa, AI adoption is accelerating, driven by the need for enhanced public service delivery, more effective conflict analysis, and improved governance systems. However, this rapid proliferation also presents significant challenges, including ethical concerns, cybersecurity vulnerabilities, and the potential for misuse by both state and non-state actors. Against this backdrop, tomorrow’s PSC session is expected to explore both the opportunities and risks of AI, with a particular focus on its implications for peace and security in Africa.

In the outcome document of the previous session, the PSC stressed the importance of establishing a Common African Position on AI. Given that Africa is predominantly a consumer rather than a producer of AI technology, the session underscored the necessity of ensuring African perspectives in shaping global AI governance frameworks. Consequently, the PSC urged the AU Commission to fast-track the development of a Common African Position on AI, addressing its implications for peace, security, democracy, and development on the continent. Additionally, the PSC requested the AU Commission to conduct a study to assess the adverse impact of AI on peace and security. It is also to be recalled that the PSC previously requested a comprehensive study on emerging technologies during its 1097th session.

Establishing the peace and security side of the implications of AI befits the mandate of the PSC. As the AU Commission follows up on these requests from the PSC, it is worth recognising and factoring in the various AU engagements on AI, such as the Continental AI Strategy and AUDA-NEPAD’s White Paper and Roadmap on AI governance. This is critical to ensure policy coherence while avoiding duplication of efforts. There are already concerns about coherence and alignment in the AU’s approach to AI governance in the context of the Continental AI Strategy and the AUDA/NEPAD White Paper, underscoring the need for the follow-up on the PSC’s request for developing a common African position to build on these existing policy works of the AU.

The Framework for the Continental AI Strategy, endorsed during the 44th Extraordinary Session of the Executive Council, addresses peace and security in several sections, emphasising both the opportunities and risks AI presents. The document identifies peace and security as a priority sector where AI can have a transformative impact, particularly in conflict resolution, safety, and security, aligning with the AU’s Agenda 2063 aspirations. It also highlights AI governance and regulatory challenges, particularly in military applications, warning that AI could exacerbate conflicts through inaccurate predictions or deployment of autonomous weapon systems. Additionally, the framework raises concern about disinformation, misinformation, cybersecurity threats, and military risks, calling for the establishment of an expert group to assess AI’s impact on peace and security in Africa.

At its 1214th session, the PSC also requested the AU Commission to establish a high-level advisory group on AI for governance and military applications, with a mandate to report every six months. It is and has to be understood that this is not different from the expert group that the AU strategy proposed. In response, the Department of PAPS released a Terms of Reference in February 2025 for the establishment of the AU Advisory Group on Artificial Intelligence and its Impact on Peace, Security, and Governance. Subsequently, on 6 March 2025, PAPS and the AU Infrastructure and Energy Department convened the inaugural meeting of the Advisory Group, bringing together experts from Africa’s five regions, representatives from PAPS, the AU Infrastructure and Energy Department, the United Nations Office of Information and Communications Technology (UNOICT), and the co-Chair of the AU Network of Think Tanks for Peace (NETT4Peace). Therefore, in tomorrow’s PSC session, discussions are expected to follow up on this initiative, ensuring that the Advisory Group plays a strategic role in shaping AI governance, security, and policy implementation across Africa.

Various events, including the jamming of GPS systems affecting flights reported in Eastern DRC and the deployment by the Islamic State of West Africa of armed drones, highlight not only the need for effective regulation but also the existence of the requisite infrastructure and technical capacity. Thus, one of the issues that is of interest to members of the PSC during tomorrow’s session is the question of the kind of infrastructure and technical capability required both for mitigating the risks and harnessing the benefits of AI in peace and security.

While the AUDA-NEPAD White Paper and Roadmap do not have a dedicated section on peace and security, they emphasise AI’s role in governance, security, and conflict prevention, showcasing best practices that illustrate AI’s potential. AI serves as a strategic tool for peacebuilding, with applications in conflict prevention, combating disinformation, mediation, and counterterrorism. For example, South Africa’s ‘Shot Spotter’ technology, which detects gunfire to prevent urban violence, demonstrates how AI can enhance early warning systems by analysing social networks, media, and government reports to identify emerging threats and prevent crises. In this regard, the PSC at its 1247th session has also emphasised the significance of further strengthening the institutional capabilities of the Continental Early Warning System (CEWS), particularly by integrating advanced AI, machine learning, and predictive analytics technologies.

AI also plays a role in conflict prevention and resource-driven disputes, as illustrated by Mali’s partnership with the Water, Peace, and Security (WPS) Partnership, which uses AI to predict and mitigate conflicts arising from water scarcity. This demonstrates how AI-driven early warning systems can be used to analyse socio-economic and environmental data for proactive conflict resolution. The AI-powered surveillance and security systems that are being employed in some countries for security by identifying threats and tracking criminal activities are susceptible to abuse and misuse of AI by non-state actors that designed the AI system. Therefore, the PSC needs to assess mechanisms for human rights-centered AI governance and regulatory frameworks, which is critical to prevent abuse of such technologies.

In disaster management and humanitarian aid, Rwanda and Tanzania’s automated drone delivery systems ensure the rapid delivery of medical supplies to conflict zones and remote areas, showcasing how AI can strengthen crisis response efforts. Similarly, Rwanda’s anti-epidemic robots, deployed during the COVID-19 pandemic, highlight AI’s role in crisis management—a critical aspect of national security and emergency response.

Given AU’s experience with cyberattacks that disrupted its digital systems, another critical area of interest for tomorrow’s session is how to mitigate the vulnerabilities that the deployment of AI exposes to cyberattacks and how to harness its utility to fend off such attacks. AI plays a critical role in cybersecurity, enhancing threat detection, vulnerability assessments, and the protection of critical infrastructure. By analysing financial transactions and identifying irregular financial patterns, AI aids counterterrorism efforts by disrupting illicit funding channels, making it a valuable tool in the fight against terrorism and organised crime. In this context, the PSC is expected to examine strategies to build on recent commitments by member states to strengthen data protection and cybersecurity governance, particularly in light of the ratification of the AU Malabo Convention in June 2023. This discussion will be essential in advancing Africa’s cybersecurity framework and fostering a coordinated, continent-wide approach to securing digital infrastructure.

The expected outcome of the session is a communiqué. The PSC is expected to emphasise the need for a strategic approach to AI governance, ensuring alignment with relevant AU and UN frameworks. It may call on AU member states to strengthen national cybersecurity strategies in line with the AU Malabo Convention, implementing robust data protection laws and AI-driven cybersecurity tools. Additionally, the PSC may advocate for the development of an AU-wide regulatory framework on AI ethics, ensuring compliance with human rights standards while preventing mass surveillance and privacy violations. To promote policy coherence, the PSC is also expected to stress the importance of aligning the Common African Position on AI with existing continental AI initiatives, such as the Continental AI Strategy, AUDA-NEPAD White Paper, and AI Roadmap. Regarding AI’s role in peace, security, and governance, the PSC may urge the enhancement of the Continental Early Warning System (CEWS) through the integration of AI-powered predictive analytics, machine learning, and big data analysis to improve conflict detection and response mechanisms. It may further call for greater investment in AI-driven disaster response solutions, ensuring AI is integrated into continental disaster risk reduction frameworks while also encouraging capacity-building initiatives that enable regional and national conflict prevention institutions to leverage AI for real-time data analysis and crisis response. The PSC may also emphasise the need for building a digital infrastructure and technical capability that are fit for and tailored to the development and security needs as well as socio-cultural specificities of Africa as necessary conditions for deploying AI in a way that maximizes its benefits and mitigates its risks. As for the newly established AU Advisory Group on AI, the PSC may encourage the group to harmonise recommendations from various AI policy documents and provide guidance on policy implementation across AU member states, ensuring a cohesive and well-coordinated approach to AI governance and security across the continent having regard to the needs of Africa and its position vis-à-vis the design and deployment of AI. The PSC may also call for stronger African representation in global AI regulatory and governance bodies, ensuring that African perspectives and priorities actively influence the development of international AI policies and standards.

Deradicalisation as Leverage for the Fight Against Violent Extremism in Africa

Deradicalisation as Leverage for the Fight Against Violent Extremism in Africa

Date | 18 March 2025

Tomorrow (19 March), the African Union (AU) Peace and Security Council (PSC) will convene its 1266th session to discuss the theme of ‘Deradicalisation as a Leverage for the Fight against Violent Extremism in Africa.’

The Permanent Representative of Morocco to the AU and Chairperson of the PSC for March, Mohammed Arrouchi, will deliver the opening remarks, followed by a presentation from the AU Commissioner for Political Affairs, Peace, and Security (PAPS), Bankole Adeoye. Parfait Onanga-Anyanga, Special Representative of the United Nations (UN) Secretary-General to the AU and Head of the UN Office to the AU (UNOAU) is also expected to deliver a statement.

This is not the first time that the PSC has dedicated a session on deradicalisation as a strategy to fight terrorism and violent extremism. On 7 October 2022, during its chairship of the PSC, Morocco convened a ministerial-level session on the same theme, ‘Development and Deradicalisation as Levers to Counter Terrorism and Violent Extremism.’ The communiqué adopted at that session identified radicalisation and underdevelopment as key factors fostering terrorism and violent extremism in Africa. Emphasising comprehensive, multidimensional, and human rights-sensitive approaches, the PSC highlighted the need to address all structural root causes, drivers, and facilitators of radicalisation and violent extremism.

A major outcome of that session was the endorsement of reconciliation, dialogue, and negotiation as critical tools in countering terrorism. Relatedly, it underscored ‘the critical role of the media, religious institutions, educational and cultural institutions in countering terrorist narratives, deradicalisation, and in promoting inter-faith dialogue, tolerance and peaceful coexistence.’ These echo findings from our Special Research Report on the growing threat of terrorism in Africa, which highlights that ‘the recognition of the essentially political, governance, and development nature of the conflict dynamics in which insurgent groups identified as terrorists operate necessitates that negotiation and dialogue with members of such groups forms part of the political strategy for settling the conflict involving these groups.’ Furthermore, the PSC requested the AU Commission to develop a compendium of African national reconciliation best practices for the Council’s consideration. It also called for the inclusion of strategies to counter radicalisation and extremist ideologies in the envisaged review of the African Plan of Action on the Prevention and Combating of Terrorism and Violent Extremism. Tomorrow’s session presents an opportunity to follow up on progress in implementing these and other related decisions adopted by the PSC at various times to combat terrorism and violent extremism in the continent.

This session takes place against the backdrop of a persistent and escalating threat of terrorism and violent extremism. The Sahel region remains the global epicentre of terrorism, accounting for 51 per cent of all terrorism-related deaths in 2024, according to the newly released Global Terrorism Index 2025, an annual report by the Institute for Economics and Peace (IEP). The region has also witnessed a nearly tenfold increase in terrorism-related deaths since 2019. Six of the ten most affected countries are in Africa—Burkina Faso, Mali, Niger, Nigeria, Somalia, and Cameroon. Despite a decline in both attacks and fatalities, Burkina Faso remains the most impacted country, accounting for one-fifth of all terrorism-related deaths worldwide. Meanwhile, Niger recorded the highest increase in terrorism-related deaths globally, rising by 94 per cent—highlighting the fragility of progress in countering terrorism.

Tomorrow’s discussion is important in spotlighting political, social, cultural and socio-economic approaches to counterterrorism, particularly given the dominance of hard security as the prevailing policy thinking and response. As outlined in our aforementioned special research report, an analysis of AU policy decisions—from the AU Assembly to the PSC—reveals particular emphasis on hard security measures in combating terrorism.

Building on the 1111th session of the PSC and the increasing recognition in the AU Counter Terrorism Centre for a more comprehensive approach, tomorrow’s session can take forward the shift to a multidimensional strategy that prioritises the political governance, social, cultural and socio-economic, development dimensions. Given its focus on deradicalisation, the session is also expected to draw attention to public policy measures that facilitate social cohesion, reconciliation and inclusion, opportunities for rehabilitation and reintegration, and religious teachings and practices that advance tolerance and moderation.

In terms of best practices, it is expected that the session may put the spotlight on Morocco’s success in deradicalisation programs. Morocco has been classified among the countries with ‘zero risk’ of terrorism worldwide, ranking first in North Africa according to the GTI 2025. The report, which assesses the impact of terrorist attacks across 163 countries, places Morocco 100th—marking significant progress from its 76th position in 2022 among countries affected by terrorism. This shift moves Morocco into the category of countries with ‘no impact’ from terrorism, making it one of the safest in the world, registering scores of zero, meaning the country had been free of terrorist activity for at least the past five years. This track record is not due to a lack of threats. In fact, Morocco remains a target for terrorist groups due to its location at the crossroads of Africa, Europe, and the Arab world. However, its success in containing the threat is largely attributed to its multidimensional counterterrorism strategy.

The 2003 Casablanca attacks marked a turning point in Morocco’s counterterrorism approach, prompting a comprehensive strategy—often described as a ‘tri-dimensional counterterrorism strategy’—that integrates security measures, socio-economic development, and religious oversight. Law 03.03, enacted shortly after the attacks, established a stronger legal framework, while from a security perspective, enhanced border security and intelligence capabilities have reportedly helped dismantle over 200 terrorist cells and arrest more than 3,500 individuals on terrorism-related charges over the past two decades, potentially preventing over 300 planned attacks.

A key pillar of Morocco’s counterterrorism strategy is its deradicalisation programs, notably the Moussalaha (Reconciliation) initiative, which has rehabilitated hundreds of detainees. As part of efforts to counter extremist narratives, Morocco’s Ministry of Endowments and Islamic Affairs has developed an educational curriculum for nearly 50,000 imams and female Islamic guides (mourchidates). As summarised in a contribution to the GTI 2022, key lessons from Morocco’s counterterrorism efforts include its deep understanding of the threat, the interconnectedness of its counterterrorism methods, the combined application of soft and hard measures, the facilitation of information-sharing practices, and the promotion of international cooperation as the sine qua non of counterterrorism.

As this experience attests and our research report established, while security measures remain essential in addressing immediate terrorist threats, they alone cannot fundamentally alter the continent’s terrorism landscape without addressing the underlying socio-economic and political conditions that fuel extremism. As highlighted in our special research report, governance deficiencies, community grievances, and structural vulnerabilities create fertile ground for terrorist groups to emerge and thrive. Given the limitations of a security-heavy approach, it remains imperative for the PSC to prioritise investments in socioeconomic development, governance reforms, and humanitarian interventions alongside security responses. Despite being in a neighbourhood that witnessed a major expansion of the terrorist threat, another country that largely shielded itself from the impacts of terrorism is Mauritania. As with Morocco, this is not attributable to the reliance on the security approach but also to the use of instruments that advance the prevention of violent extremism and deradicalisation.

Encouragingly, in recent years, PSC discussions have increasingly recognised the need to address the structural root causes of terrorism. For instance, the Declaration of the April 2024 High-Level African Counter-Terrorism Meeting in Abuja, endorsed by the PSC during its 1219th session, emphasised the importance of complementing military action with political solutions. It called for policies to counter economic, religious, and cultural discrimination, promote inter-community dialogue, and strengthen social cohesion. The Declaration also underscored the need to invest in education, integrate counterterrorism efforts with SDG 16 and Agenda 2063, and adopt community-led approaches. Additionally, it highlighted the importance of countering terrorist propaganda that exploits inter-religious tensions and the clash of civilisation narratives.

The expected outcome of the session is a communiqué. The PSC may underscore the importance of adopting a comprehensive and multidimensional counterterrorism strategy that integrates both hard and soft approaches, including security measures, legal frameworks, socio-economic development, and programs for countering radicalisation and deradicalisation. It may also emphasise the need for national reconciliation, social cohesion, and inter-community dialogue to address the structural challenges that fuel terrorism and violent extremism while highlighting the importance of facilitating platforms for lesson learning and experience sharing. In this regard, the PSC may reiterate its call from the 1111th session for the AU Commission to develop a compendium of best practices on national reconciliation in Africa. Recognising the role of the UN Office of Counter-Terrorism Programme Office in Rabat in supporting Member States’ capacity-building efforts, the PSC may encourage Member States to effectively leverage its resources and enhance coordination with Nigeria’s recently upgraded Regional Counter-Terrorism Centre. Furthermore, the PSC may use this opportunity to follow up on the implementation of its previous decisions, such as the full operationalisation of the AU Ministerial Committee on Counter-Terrorism and the PSC’s Sub-Committee on Counter-Terrorism.

Informal consultation with countries in political transition

Informal consultation with countries in political transition

Date | 17 March 2025

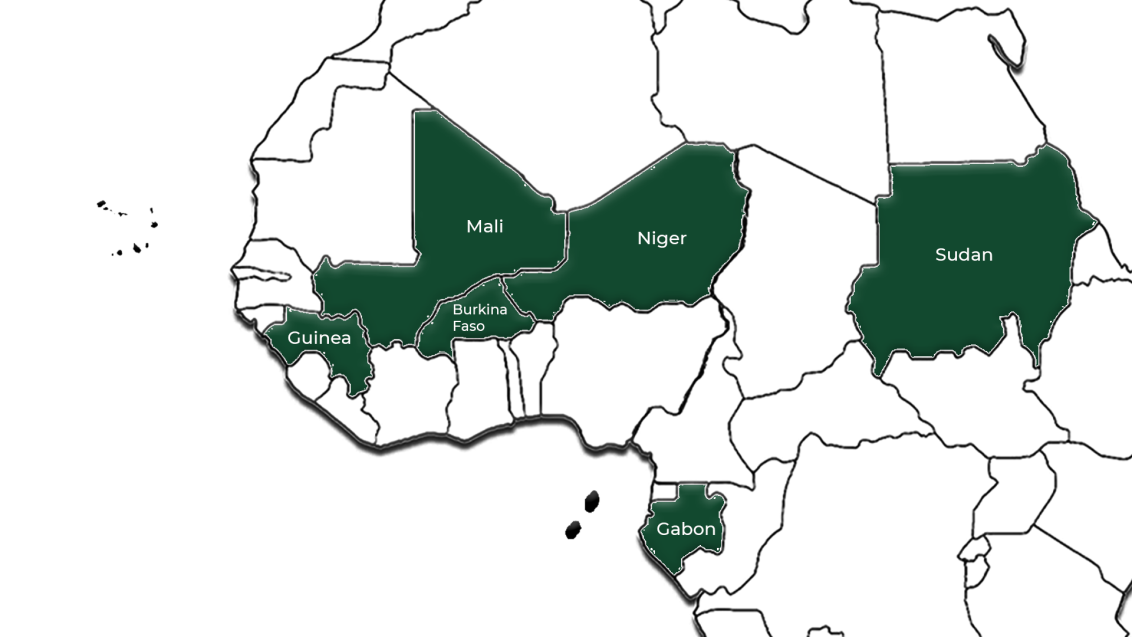

Tomorrow (18 March), the African Union (AU) Peace and Security Council (PSC) will hold an informal consultations with Burkina Faso, Gabon, Guinea, Mali, Niger and Sudan at the ambassadorial level.

Informal consultation with countries undergoing political transitions was incorporated into the PSC’s repertoire of working methods following its decision during the 14th Retreat on Working Methods, held in November 2022. The conclusions of the retreat introduced these consultations as a mechanism to facilitate direct engagement with representatives of countries suspended from participation in the AU due to unconstitutional changes of government, in line with Article 8(11) of the PSC Protocol. Since then, two such consultations have been held in April and December 2023.

The last time the PSC held informal consultations with countries in political transition was in December 2023. Since then, the PSC convened its 1212th session on 20 May 2024 as a formal meeting to receive updated briefings on the political transitions in Burkina Faso, Gabon, Guinea, Mali, and Niger. The PSC also conducted a field mission to Gabon in September 2024. Tomorrow’s session presents an opportunity for the PSC and countries in political transition to exchange views on the latest developments and provides a platform for candid discussions on concerning trends affecting the restoration of constitutional order in these countries.

During tomorrow’s informal consultation it is expected that some of the representatives of the affected countries will raise concerns on how suspension from the AU continues to affect effective engagement of the AU. It is worth recalling that one of the reasons for the use of the informal consultation is to provide a platform for engagement between the PSC and the affected countries. As a manifestation of the fact that suspension does not sever AU’s responsibilities towards affected countries, the PSC undertook missions to some of these countries. In September 2024, the PSC undertook a mission to Gabon. The following month, the PSC spent a day in Port Sudan on a field visit as well.

Yet, it remains unclear how these engagements have changed the dynamics of AU’s role in relation to these countries. For example, in the case of Sudan, it appears that the expectation from Port Sudan was for the lifting of Sudan’s suspension. Indeed, this issue was put on the agenda of the PSC during its session on 9 October. After debating the matter, a divided PSC adopted a principled position of upholding the suspension. This is not surprising, considering that there is no political process in Sudan to warrant the lifting of the country’s suspension from AU activities.

This outcome affirms that the effort to improve AU’s engagement in these countries cannot be reduced to the narrow issue of the lifting of suspension. Principally, the expectation, also from earlier experiences, is that the AU deploys and maintains robust diplomatic engagement focusing as relevant on two areas. First, this involves instituting a dedicated mechanism to work with the national actors on the transitional process on a sustained basis. When the AU suspends a state from its activities, its responsibility for sustained engagement becomes higher than usual. Second, the AU is rightly expected to initiate and deploy all the relevant policy measures to address the peace and security challenges facing these countries. For a long time, the focus on the unconstitutional change of government has overshadowed the imperative for the AU to elevate its policy action to address the security threats facing, most notably, the Sahelian countries in transition. This has led to charges of AU being absent in having an active role with respect to the existential threat facing these countries. A case in point is the fact that the AU has not for a long time filled the position of the head of its mission in Mali and Sahel (MISAHL), which has been vacant since the departure of Mamane Sidikou in mid-2023.

Indeed, with respect to the countries in the Sahel, the PSC itself, at its 1212th session, rightly expressed concern about ‘the deteriorating security situation in the Sahel region due to the activities of terrorist and insurgent groups, and the attendant dire humanitarian situation.’ Despite this concern and the fact that the persistence of conflicts involving terrorist groups is at the core of the security and institutional crises facing Burkina Faso, Niger and Mali, the PSC, once again, failed to consider concrete steps for helping to address, this principal challenge. Putting a spotlight on this lack of meaningful action, the AU Commission Chairperson, in his address to the AU Assembly on 17 February 2024, posed the following rhetorical questions: ‘How should we stop watching terrorism ravage some of our countries without doing anything? How can we accept just watching African countries destroyed, and entire regions engulfed by tremors and tsunamis, without doing anything significant?’

In terms of instituting a dedicated mechanism to work with national authorities for facilitating transitional processes, it can be discerned from the outcome of the 1212th session of the PSC that the AU neither deployed effective mechanisms nor ensured the effective functioning of existing ones. As a result, the PSC reiterated its request for the AU Commission ‘to appoint a High-Level Facilitator at the level of sitting or former Head of State to engage with the Transitional Authorities.’ Additionally, taking note of ‘the leadership vacuum within the African Union Mission for Mali and Sahel (MISAHEL)’ at a time when the AU needs active engagement in these countries, the PSC requested ‘the Chairperson of the AU Commission to ensure the nomination of a High Representative, which remains a crucial interface in ensuring collective oversight between the Commission, Council, and the Countries in transition.’ The AU Commission Chairperson failed to act on this demand and his term came to an end, leaving MISAHEL without a leader.

One notable and positive development that emerged since the 1212th PSC meeting is the decision of the AU to use the Crisis Reserve Facility of the Peace Fund to provide symbolic funding for supporting the efforts of Burkina Faso, Niger and Mali in the fight against terrorist groups with allocation of $ 1 million to Burkina Faso and $ 500,000 each to Niger and Mali.

In terms of enhancing AU’s role in the fight against terrorism in the Sahel, the AU may build on this recent support and adopt a Sahel stabilisation strategy supported by the activation of the decision to deploy 3000 troops to the Sahel made by the AU Assembly at its 33rd Ordinary Session [Assembly/AU/Dec.792(XXXIII)] in February 2020. It is a good time to have such a strategy and deployment considering the decision of Burkina Faso, Niger and Mali as the Alliance of Sahel States (ASS) to deploy a new regional 5000 strong force to fight against terrorism.

It is expected that some of the representatives of the countries concerned may put a spotlight on the lack of consistency of the AU in applying the rules on unconstitutional changes of government. This may become a key area of contestation, particularly as it relates to the eligibility of the coup makers for elections that may be held for restoring constitutional order. Despite the fact that the PSC affirmed the AU rule that the members of the Transitional Military Council in Chad are ineligible for election, the Chairman of the Council, Mahamat Idriss Déby, oversaw an orchestrated national dialogue and constitutional referendum that enabled him to run for elections, ultimately being declared the winner of the 6 May 2024 presidential election. The PSC’s failure to enforce its principles and decisions against the eligibility of military authorities in elections has put the AU in the difficult position of not being able to uphold this principle with respect to military leaders in other countries in transition, as highlighted by the 16 September 2024 edition of Amani Africa’s Ideas Indaba.

Another issue likely to receive attention in tomorrow’s engagement is the duration of the transition period. In Burkina Faso, the transitional timeline initially agreed to come to an end by 2 July 2024 has been extended by an additional five years. Similarly, Mali’s agreed timeline with ECOWAS for a February 2024 transition has been postponed indefinitely. In Niger, no clear transition timeline has been announced, though the junta proposed a three-year period. Guinea, which had committed to organising elections by the end of 2024 under a 24-month transition agreement with ECOWAS, also failed to meet this deadline. In Sudan, the prospect of a return to civilian rule has become a distant luxury as the ongoing conflict plunges the country into one of the world’s worst humanitarian crises. Meanwhile, Gabon’s transitional government has set 12 April 2025 as the date for the presidential election to end military rule, which has been in place since August 2023. Earlier this month, military leader General Brice Oligui Nguema announced his intention to run for President in the upcoming election. The variations in the specific political, institutional and security context of these countries also underscore that a generalised approach to AU’s role in respect to these countries would be inadequate and unfit and require a policy approach tailored to the specificities of each.

Tomorrow’s informal consultation is also expected to touch on the issue of the severing of ties by three central Sahel countries with ECOWAS, dealing a major blow to AU’s ideal of regional integration. On 15 December, during its 66th ordinary session, ECOWAS approved the withdrawal of Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger (who formed their own Alliance of Sahel States (AES abbreviated in French) from the regional bloc, effective 29 January 2025. However, it also decided to institute a six-month transitional period (29 January–29 July 2025) for these countries, leaving the door open for them to reverse their decision. In a step that signals the determination of the countries to exit ECOWAS, the three states unveiled a new common passport of the Confederation of Sahel States, which is expected to come into circulation the same day the exit from ECOWAS takes effect. That the separation of AES states from ECOWAS took effect is an indictment on the AU’s role of advancing regional integration, underscoring its inability, if not failure, to play the role of mediating between the two.

No outcome document is expected from tomorrow’s informal engagement.

Consideration of the situation in South Sudan

Consideration of the situation in South Sudan

Date | 17 March 2025

Tomorrow (18 March), the African Union (AU) Peace and Security Council (PSC) will convene its 1265th session to discuss the situation in South Sudan.

The Permanent Representative of Morocco to the AU and Chairperson of the PSC for March, Mohammed Arrouchi, will deliver the opening remarks, followed by an introductory report from the AU Commissioner for Political Affairs, Peace, and Security (PAPS), Bankole Adeoye. The Special Representative of the AU Commission Chairperson to South Sudan is also expected to brief the Council. As per the applicable practice and established procedure, a representative of South Sudan is expected to make a statement as a country concerned. A representative of the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD) and the Special Representative of the Secretary-General and Head of the UN Mission in South Sudan may also deliver statements.

Tomorrow’s session came amidst heightened tensions between longtime rivals President Salva Kiir and First Vice President Riek Machar, following the 4 March incident when the White Army, Nuer militia linked with Riek Machar, overran a South Sudan People’s Defence Force (SSPDF) base in Nasir, Upper Nile State—a strategic town on the South Sudan-Ethiopia border. The violence was triggered reportedly due to disagreements over the replacement of the existing SSPDF in Nasir stationed for close to eight years with a combined force of SSPDF, Agwelek, and Abushok militias.

Tensions had been building since January and February, not only in Upper Nile State but also in Western Equatoria and Western Bahr el Ghazal states. On 27 February, it appears that Machar requested a face-to-face meeting with President Kiir to address deteriorating security situations in these regions. Machar cited attacks by SSPDF forces on areas controlled by SPLM-IO in Western Equatoria and Western Bahr el Ghazal and accused SSPDF and allied militias of violating the Permanent Ceasefire Agreement by deploying forces to Nasir, including the Agwelek and Abushok militias. This deployment was seen as a violation of the 2018 revitalised peace agreement, which envisages the deployment of the Necessary Unified Forces.

In response to escalating tensions, on 27 February, the African Union Mission in South Sudan (AUMISS), the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD), the United Nations Mission in South Sudan (UNMISS), and the Reconstituted Joint Monitoring and Evaluation Commission (RJMEC) expressed deep concern over the deteriorating security situation in Upper Nile State, as well as clashes in Western Equatoria and Western Bahr el Ghazal involving signatory parties to the Revitalised Agreement on the Resolution of the Conflict in the Republic of South Sudan (R-ARCSS). The statement warned that failure to address these incidents could undermine the Permanent Ceasefire, urging all parties to utilise established mechanisms under the R-ARCSS to de-escalate tensions and restore calm.

This call went unheeded, and tensions escalated into violence in Nasir on 4 March, followed by the arrest of several senior SPLM/A-IO military and government officials, including a deputy military chief and two ministers allied with Machar in the capital, Juba. The situation worsened on 7 March when an attack on a UNMISS operation to evacuate stranded SSPDF personnel resulted in tragic casualties, including the late General Majur Dak, several soldiers, and a UN crew member.

Despite President Kiir’s assurance on 7 March that South Sudan would not revert to war, tensions remain high in Juba and elsewhere, prompting widespread concerns about the potential collapse of the 2018 Revitalised Peace Agreement, which ended a five-year civil war claiming nearly 400,000 lives. In his briefing to IGAD’s 43rd extraordinary summit, Executive Secretary Workneh Gebeyehu warned that ‘the Nasir clashes are the latest episode in a series of incidents and cyclic violence pushing South Sudan ever closer to the brink of war.’ Indicating the gravity of the situation, reports suggest that Uganda has deployed special forces to Juba despite denials by South Sudan’s government.

Against these developments, regional and international organisations reacted. On 8 March 2025, the Chairperson of the AU Commission issued a statement expressing deep concern over the escalating tensions and clashes, calling for an immediate cessation of hostilities and reaffirming the AU’s longstanding appeal for South Sudanese parties to fully implement the revitalised peace agreement. IGAD also convened its 43rd extraordinary summit of Heads of State and Government on South Sudan, held on 12 March 2025. In the communiqué adopted at the summit, IGAD urged the parties to immediately de-escalate tensions, demanded the release of detained officials, instructed the Ceasefire and Transitional Security Arrangements Monitoring and Verification Mechanisms (CTSAMVM) to investigate the Nasir clashes and the attack on the UN helicopter to establish facts and ensure accountability, and called for the reactivation of various security mechanisms impacted by the arrests. The regional bloc further agreed to form an IGAD Ministerial-level sub-committee on South Sudan to engage and monitor the restoration of calm and the implementation of the revitalised peace agreement. The Sub-committee was tasked with travelling to Juba immediately to assess modalities for initiating inclusive dialogue.

The renewed tensions are unsurprising given the lack of meaningful progress in implementing key provisions of the revitalised peace agreement, including drafting a new constitution, preparing for elections, and deploying the Necessary Unified Forces (NUF). In September 2024, the parties to the peace agreement extended the transitional period by another two years, pushing the long-awaited first elections to December 2026 without a clear plan for implementing the new transitional roadmap within the agreed timeline.

Delays in deploying the NUF, a critical component of the agreement under chapter two essential for the country’s peace and stability, have become a major obstacle to its full implementation. Reports indicate that since the graduation of 53,000 unified forces in phase one, only seven per cent of the required 83,000 have been deployed, while the long-overdue training for phase two has yet to commence due to a lack of funding. The government’s failure to allocate the necessary resources for training has been a key factor in these delays. Moving forward, prioritising phase two training and ensuring the full deployment of the unified forces at their required strength of 83,000 remains critical to enhancing security, addressing rising subnational violence, and preventing incidents like the clashes on 4 March.

As the IGAD Executive Secretary noted in his briefing to the extraordinary summit, mechanisms established to oversee security arrangements, such as the Joint Defence Board (JDB), have fallen into disuse, while mutual confidence within the Presidency, as established by the agreement, has been gravely undermined. The JDB, composed of chiefs of staff, directors general of the national security service, police, and other organised forces, is mandated to exercise command and control over all forces under the revitalised peace agreement. However, its failure to convene regular meetings and prevent escalating tensions has further weakened security arrangements. Ensuring the full functionality of the JDB is now more urgent than ever.

The spillover of Sudan’s conflict may be another factor behind the renewed tensions in South Sudan. According to a recent report on the fighting in South Sudan, one major impact is South Sudan’s economic crisis, triggered by damage to its main oil export pipeline near Khartoum amid fighting between the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and the Rapid Support Forces (RSF). This disruption has cost South Sudan two-thirds of its revenue and fueled widespread discontent. As Sudan’s conflict drags on, South Sudan appears to be struggling to maintain neutrality between the two warring parties, SAF and RSF. Reports indicate that economic pressures have drawn President Kiir closer to the RSF and its alleged backer, the UAE, a shift further intensified by the RSF’s alliance with the SPLM-North, a Sudanese rebel group aligned with Juba. What makes the suspicion about Port Sudan’s possible hand is the interest of the SAF in using its allies in South Sudan to squeeze RSF out of the areas on the border with South Sudan.

The expected outcome of tomorrow’s session is a communiqué. The PSC is likely to welcome the convening of IGAD’s 43rd Extraordinary Summit and endorse its outcomes, particularly the decision to establish an IGAD Ministerial-level sub-committee on South Sudan. It may call on the AU Commission to coordinate with this committee to facilitate dialogue and ensure the full implementation of the revitalised peace agreement to prevent further violence and the risk of renewed conflict. Expressing deep concern over the recent violence in Nasir County, Upper Nile State, the PSC may stress the need for de-escalation and urge parties to uphold the peace agreement. In line with IGAD’s summit conclusions, it may call for the immediate release of detained officials as a critical de-escalation measure. The PSC may also condemn the attack on the UN aircraft and the death of UN personnel, which could constitute a war crime. In this regard, it may support IGAD’s decision to conduct an investigation, through CTSAMVM, into the Nasir clashes and support the UN’s initiatives to investigate the UN helicopter attack to ensure accountability. The PSC may further urge the parties to expedite the implementation of key provisions of the revitalised agreement, including drafting a new constitution, preparing for elections, and deploying the Necessary Unified Forces (NUF). It may also call for strengthening oversight mechanisms such as the Joint Defence Board. The PSC may call on the AU High-Level Ad Hoc Committee for South Sudan (C5) to dispatch to South Sudan a high-level mission as a critical step to de-escalate the situation and prevent both the relapse of South Sudan into conflict and the risk of merger of the conflict in Sudan into South Sudan. Finally, it may request the AU Commission to put in place an emergency task force dedicated to the situation in South Sudan, both for monitoring and crafting interventions for preventive diplomacy.