Civil-military relations and conflict management in Africa

Civil-military relations and conflict management in Africa

Date | 17 September 2024

Tomorrow (18 September), the African Union (AU) Peace and Security Council (PSC) will convene its 1232nd session to discuss civil-military relations in Africa as an important factor for enhancing conflict management in the continent.

Following opening remarks by Churchill Ewumbue-Monono, Permanent Representative of Cameroon to the AU and the Chairperson of the PSC for the month of September, Bankole Adeoye, AU Commissioner for Political Affairs, Peace and Security (PAPS), is expected to make a statement. Parfait Onanga Anyanga, the Special Representative of the United Nations Secretary-General to the AU and Anselme Nahmtante Yabouri, Director of the United Nations Regional Center for Peace and Disarmament (UNREC), are also expected to deliver statements.

Although the PSC planned to discuss this topic in 2022 and 2023 during Cameroon’s chairship, the session could not be held as scheduled. Hence, tomorrow’s meeting presents the PSC with the opportunity to have a dedicated deliberation on this theme.

While this is the first time that the PSC has dedicated a session on civil-military relations as a standalone thematic agenda, it would not be the first time for the PSC to address some aspects of the theme of tomorrow’s session. Some of these issues received PSC’s engagement, particularly in the context of the recent resurgence of military coups in the continent. For example, at its sessions on unconstitutional changes of government (UCG) such as the 1000th session convened following the 24 May 2021 coup in Mali and the 1030th session addressing the 5 September 2021 coup in Guinea, PSC has urged the militaries of each of these concerned member States to refrain from interfering in political processes, suggesting that political affairs fall outside of the scope of military powers. PSC’s request at its 1041st session for the Sudanese military to respect their constitutional mandate following the military takeover of power on 25 October 2021, as well as the requests at its 1016thsession on the situation in Chad and 1064th session on the situation in Guinea for the members of the militaries of these Member States to abstain from taking part in elections at the end of the transition periods are illustrative of PSC’s appreciation of the boundaries on the role of the military.

Civil-military relationship touches on a wide range of issues pertaining to the governance of the security sector and the role of the military in a state. While it was a subject of major policy and scholarly attention in the 1970s and 1980s, it has acquired particular policy significance in recent years on account of a range of developments. These include the increasing reliance of governments on military and other security forces for repressing dissent, political opposition and protests, the eruption of conflict pitting various elements of the security forces or various parts of the armed forces of a country (Ethiopia, Lesotho, South Sudan and Sudan, among others), the entanglement of the military in the political and economic processes of the state. During the past three years, the spate of military coups has put civil-military relations in the spotlight.

Tomorrow’s session offers an opportunity to debate such wider issues and challenges in the governance of the security sector as well as the resultant poor state of professionalism of the military including in terms of weak adherence to the military code of conduct and respect for human rights and international humanitarian law as well as its constitutional obligations. On the other hand, weak civilian institutions, the absence of democratic governance and constitutional checks and balances, result in the weakness of the accountability structures that can effectively manage and mediate civil and military relations. Such deeper reflection is critical to address the kind of politico-constitutional and security ills arising from the types of problematic relationships that compromise the professionalism and impartiality of the security sector and entangle it into the contested terrain of political power struggle.

As such, one of the features of civil-military relations in Africa which may draw PSC’s interest is the prevalent politicisation of the military. Such politicisation entrenches the army deep into politics, thereby depriving it of its independence from and impartiality to political power struggles between rival political and social forces in society. This also creates the interests of members of the army in being involved in politics as a means of advancing particular political ambitions. Similarly, the engagement of the army in economic activities also leads to its embeddedness in pursuing economic gains and exposure to corruption and unprofessional conduct.

Indeed, the heavy reliance of civilian political leaders on coercion and the use of security institutions including the army for purposes of guaranteeing regime security and survival presents a major challenge to civil-military relationships. Not only do such practices blur the lines of military mandates and lay a fertile ground for the oppression of citizens and violation of basic human rights and freedoms, they also can lead to the fragmentation of the army by giving rise to different factions. This underscores the importance of clarifying the boundaries and limits of the control of the civilian authority over the military. Of significance in this respect is respect of constitutionally established rules that are key to guarantee both the constitutionality of the orders that the army is expected to follow from civilian leadership and maintain the army’s integrity and impartiality. As important is the adoption of minimum legal standards properly outlining the type and scope of law enforcement activities which fall within the mandates of the military and identifying the circumstances upon which armies may be deployed for managing internal security challenges.

The importance that is attached to this subject can also be gleaned from the AU’s Post Conflict Reconstruction and Development (PCRD) Policy and AU’s Security Sector Reform Policy. Of particular note in this respect is the PCRD policy’s stipulation calling for the establishment of ‘mechanisms for the democratic governance and accountability of the security sector’ and the creation of ‘appropriate and effective oversight bodies for the security sector, including parliamentary committees, national ombudsperson, etc’.

In some cases, as demonstrated in the recent coups in Burkina Faso, Chad, Mali and Niger, there is also the issue of the loss of confidence of their militaries in civilian leaders when they fail to provide them with the necessary material and moral support. Such leadership failures, in the context of heavy casualties suffered by members of the army due to terrorist attacks, lead to deepening frustrations and resentment against the civilian leadership. This can easily boil over when the civilian leadership is also perceived to be engaging in or tolerating corruption that diverts resources away from supporting the work of the army. For example, in the case of Burkina Faso, the lack of effective leadership by the democratically elected leaders in addressing terrorism, insurgency and instability that has gripped the country and reports of corruption were presented as justification for the military’s intervention through overthrowing the elected civilian leaders.

Management of security sector reform (SSR) processes in member States undergoing transitions is also an essential part of averting potential relapse as experienced in member States such as Mali and Sudan. While the speedy restoration of constitutional order in member States undergoing transitions is well within the spirit of AU norms banning UCG, restoration of constitutional order without the necessary SSR that tackles the security sector governance issues that precipitated the coup would lead to a repeat of the coup, as the experience in Mali after the 2012 coup aptly illustrates. The importance therefore of implementing and making use of the AU SSR Policy as a critical instrument for achieving constitutionally sound civil-military relationship cannot be overemphasised.

The AU SSR Policy recognises ‘the linkages between an effective and democratically governed security sector and peace and security.’ With respect to professionalism, it envisages the importance of ‘the provision of transparent, accountable and equitable recruitment mechanisms, appropriate training, equipment and gender compliance.’ The provision in the policy for ‘strengthening of (transparent) procurement policy and procedures for the purchase, supply and disposal of all security equipment’ is also critical for addressing issues of corruption. One recent analysis echoed Transparency International’s rating that roughly half of all security sectors that face critical or very high level of risk of corruption are in Africa.

The management of civil-military relations is of importance not only in the context of UCG and to member States in transition, but also with respect to broader governance issues. The implementation of codes of conduct that are in line with the constitutional obligations and the international human rights and international humanitarian law standards is key. Also of significance is the need for regularly updating the professional standards, the provision of the requisite supplies and benefits and the technical competence of the military. It is therefore critical to consider the crisis in civil-military relations as part of AU’s framework for early warning and conflict prevention.

The outcome of tomorrow’s session is expected to be a Communiqué. The PSC may emphasise the need for paying particular attention to civil-military relations as a critical component of advancing institutional stability, constitutional rule and peace and security. It may also underscore the need for careful design of the civil-military relations dimension of peace agreements and due attention to the implementation of this aspect of peace agreements as a critical element of preventing the relapse of countries in transition back to instability and conflict. The PSC may also call for the updating by member States of existing military codes of conduct to make them up to date and compliant with standards of impartiality and independence from politics, and basic human rights and international humanitarian law standards. It may underscore the imperative of protecting the military from being dragged into political contestation between various political forces and preventing its politicisation by those in power. It may also underscore the need for integrating issues in civil-military relations as part of AU’s framework for early warning and conflict prevention. The PSC may call for the use of the AU SSR Policy formwork in countries that experienced military coups as a basis for ensuring successful SSR to prevent the recurrence of coups. PSC may also seek advice from the Military Staff Committee (MSC) on how AU norms and policy instruments can be utilised to provide guidance in addressing issues relating to civil-military relations in the continent.

Is the African Union failing countries in complex political transition? Insights from the Peace and Security Council’s recent session

Is the African Union failing countries in complex political transition? Insights from the Peace and Security Council’s recent session

Date | 16 September 2024

Solomon Ayele Dersso, PhD

Founding Director, Amani Africa

Following the military coups that led to their suspension, six of African Union’s member States (Burkina Faso, Gabon, Guinea, Mali, Niger and Sudan (which plunged into civil war) have been in political transitions of varying complexities. The African Union (AU) has been seized with the situation of these countries for a number of years. Apart from the fact that its various policy actions did not yield the expected results, the insights from PSC’s recent session highlight that AU’s decisions, often ignored (as in Chad in terms of non-eligibility for election and in Chad, Mali, Guinea, Burkina Faso, Gabon for completing the transition within agreed timeline) or unimplemented (as in almost all of the cases), are pushing the continental body into further irrelevance and lack of credibility.

On 20 May, the PSC convened its 1212th session which was committed to an updated briefing on political transitions in Burkina Faso, Gabon, Guinea, Mali, and Niger – countries suspended from activities of the AU in relation to unconstitutional change of governments (UCG). This session offers useful insights into the flaws in the AU’s role regarding these countries.

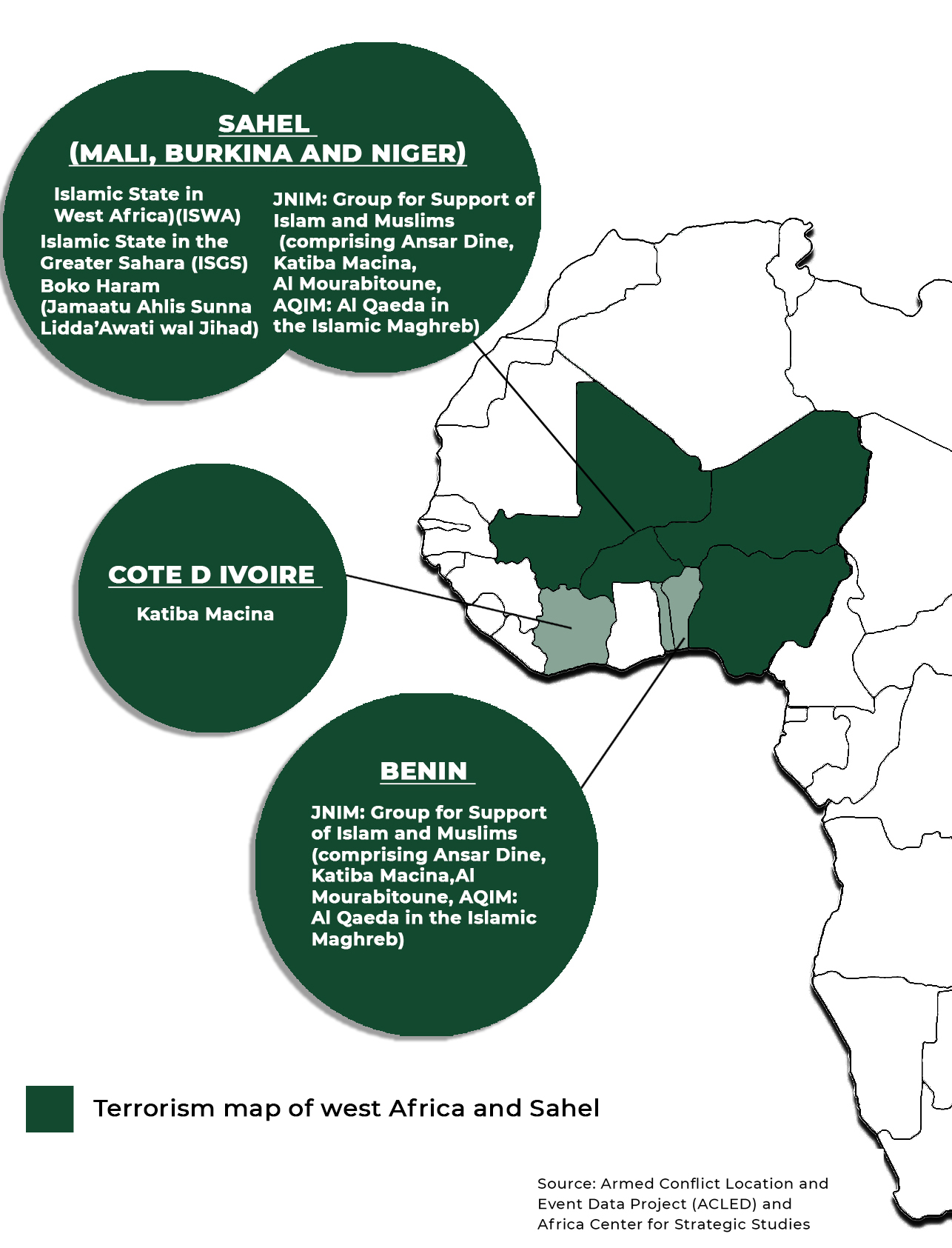

The deliberations and outcome of the session, adopted as Communiqué, centred around several issues identified as concerns with respect to countries in transition in general and those specific to the transition of individual countries. With respect particularly to countries in the Sahel, the first area of concern relates to what the PSC called ‘the deteriorating security situation in the Sahel region due to the activities of terrorist and insurgent groups, and the attendant dire humanitarian situation.’

Notwithstanding that the persistence of conflicts involving terrorist groups is at the core of the security and institutional crises facing Burkina Faso, Niger and Mali, the PSC, once again, failed to consider concrete steps for helping to address this principal challenge. Putting a spotlight on this lack of meaningful action, the AU Commission Chairperson in his address to the AU Assembly on 17 February 2024 posed the following rhetorical questions:

Considering this grave state of the situation, PSC’s response not exceeding the expression of concern once again shows the persistence of the holding of meetings that are nothing more than performative. It also manifests the resultant lack of action that the peace and security conditions warrant and hence, AU’s increasing irrelevance to the situations in the Sahel. It is remarkable that in making a generalised call towards supporting affected countries, the PSC directed the target of the support to the consequences rather than the terrorist insurgency precipitating those consequences. It thus called upon ‘the Commission, the international community and the Member States in a position to do so, to support the efforts of the Governments in the countries in transition through the provision of humanitarian assistance.’ (emphasis added) At the same time, the PSC emphasised the need for holistic solutions toward addressing structural root causes and drivers of terrorism in the region. Yet, it did not articulate what these solutions would entail nor did it proposed how the AU can support the deployment of such ‘holistic solutions.’

The other area of concern raised in PSC sessions including its 1212th session relates to the duration for the conclusion of the transition in each of these countries. It is to be recalled that 2024 marked the year during which Burkina Faso, Mali, and Guinea were expected to conduct elections to end their transition periods. However, the dialogue or consultation processes in all three countries have extended the transition period, delaying elections, indicating that election is not a priority, particularly for the countries in the Sahel. Yet, the PSC called on the transition authorities in countries ‘to ensure the strict implementation of their respective transition roadmaps, within the agreed timelines.’ With respect to Niger, the PSC tasked the AU Commission to ‘[e]xpeditiously take requisite steps in ensuring the deployment of a high-level mediation mission to Niger, to engage with the Transitional Authorities, with a view to establishing a transition roadmap in line with national and regional dispositions.’ On Mali, the PSC requested the Commission ‘to urgently organise a fact-finding mission to Mali to discuss the conclusions of the inter-Malian dialogue, and work with the transitional authorities to identify opportunities for collaboration and implementation.’ With respect to the transition process in Gabon, noting that ‘the setting of the duration of the transition for a period of 24 months and the intention to hold elections in August 2025’, the PSC expressed its rejection of ‘any further extension of the transition period’ and renewed its ‘call for a speedy return to constitutional order within the prescribed timeframe.’ It remains unclear whether the PSC communicated its rejection of the extension of the transition period in it engagement with the transition authorities during its mission to Gabon.

The third area of concern highlighted in the session was what the PSC called ‘the shrinking political and civic spaces within some countries in political transition, especially the ban on the activities of political parties, associations, civil society organisations and repression of media activities.’ In this respect, the PSC encouraged the authorities in Burkina Faso ‘to create favourable conditions for political and democratic discourses towards promoting inclusivity’, called on Guinean authorities ‘to pursue inclusive dialogue with the participation of all political, socio-economic and civil society stakeholders,’ and Malian authorities to reconsider the decision (suspending ‘political parties and activities of political associations’).’

The other area of concern involved the issue of AU’s effective role in facilitating conditions for the implementation of reform measures for successful transition and restoration of constitutional order. As the outcome of the 1212th session revealed, AU neither deployed effective mechanisms nor ensured the effective functioning of existing ones. It is on account of these deficiencies that the PSC reiterated its request for the AU Commission ‘to appoint a High-Level Facilitator at the level of sitting or former Head of State to engage with the Transitional Authorities.’ Additionally, taking note of ‘the leadership vacuum within the African Union Mission for Mali and Sahel (MISAHEL),’ the PSC requested ‘the Chairperson of the AU Commission to ensure the nomination of a High Representative, which remains a crucial interface in ensuring collective oversight between the Commission, Council, and the Countries in transition.’ The position has been vacant since the departure of Maman Sambo Sidikou in August 2023.

There is also the threat of a breakdown of the regional order in West Africa with the three central Sahelian states deciding to withdraw from ECOWAS. Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger established their own grouping called the Alliance of Sahelian States, which was recently upgraded into a confederation of Sahel States in a treaty the three states signed during a summit held early in July 2024 in Niamey, Niger.

Expressing concern and encouraging the three countries to reconsider their decision, the PSC called for ‘the resumption of dialogue and mediation between ECOWAS and Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger.’ Such generic calls without assigning a mechanism for undertaking such dialogue and mediation seem to suggest a lack of adequate appreciation of the gravity of the risk of breakdown of the regional order that this situation poses.

The other and key area of concern is the possibility of those involved in the perpetration of unconstitutional change of government becoming candidates for election. While it reiterated its ‘position regarding the ineligibility of the members of the Transitional Authorities in the election process to mark the end of the Transitions, in line with the provisions of the African Charter on Democracy, Elections and Governance (ACDEG),’ PSC’s deafening silence on Chad’s breach of this prohibition deals a major blow for its credibility and this reiteration of its position. Indeed, this lack of action on the part of the PSC on the election of members of the Chadian transitional government, particularly in view of its own clear decision on the matter, has come to be seen as setting a precedent for military leaders in the other countries in transition.

The AU is now faced with a situation in which leaders of the transitions are set to seek the same treatment as Chad. Mali and Burkina Faso have already made a decision on that end. Following the template set by the Chadian transition, last May the national dialogue in Mali concluded to extend the transition period by three more years and, similar to the 2022 national dialogue in Chad, to allow Assimi Goita to stand in the eventual election. Around the same time, a new in Burkina Faso a new Charter, adopted following consultations and extending the transition period for five years, envisages that junta leader Ibrahim Traore will be able to stand for election at the end of the five-year transition period.

As the PSC concluded its mission to Gabon undertaken during 11-13 September 2024, it would be very fitting if the PSC leveraged its engagement with the leadership of the transition authority in Gabon to dissuade the junta leader from running for election at the end of the transition process.

The foregoing analysis of the various areas of concern drawn from one of PSC’s recent sessions on countries in transition highlights the need for a complete rethinking of AU’s approach. Otherwise, AU’s role faces an increasing lack of relevance and credibility in many of these situations. AU also faces charges of failing people in the Sahel for not taking actions that go beyond expressing concern about the grave terrorist threat that created the conditions for institutional fragility and unconstitutionality.

The content of this article does not represent the views of Amani Africa and reflect only the personal views of the authors who contribute to ‘Ideas Indaba’

Reforming the multilateral system a strategic imperative not a policy choice, the Report of Africa High-Level Panel

Reforming the multilateral system a strategic imperative not a policy choice, the Report of Africa High-Level Panel

Date | 9 September 2024

Dr Netumbo Nandi Ndaitwah

Vice President of the Republic of Namibia

As a Pan Africanist and a Patron of Amani Africa, I personally attach great importance to the work of the High-Level Panel of Experts and made a determined effort, despite heavy schedule, not to let this opportunity (for launching the Panel’s Report) just to slip away.

When this high-level process, which I have the pleasure of championing, held its inaugural meeting more than a year ago in Windhoek, I shared with the members of the High-Level Panel the importance of the Panel’s work and expressed my hope for what can be accomplished. More specifically, I said

‘While many challenges [that we face today] are not new, it is clear that they are bigger in scale, unfolding in the same timeline and tend to reinforce each other. They are also taking place at a time of major global power shifts and worrying geopolitical rivalries…for the continent of Africa, this would mean that our collective effort should go beyond presenting a good case for securing the interest of Africa. It should also include articulating proposals on how to reform the multilateral system in a way that it also meets the just expectations and needs of the whole of humanity.’

I am very pleased that the Panel did not fail in its mission. Its various activities and importantly the Report it produced is highly commendable.

This report, presented well throughout and principled proposals on how to reform the multilateral system in a way that not only makes a compelling case for the representation and effective participation of Africa for it to occupy its rightful place in the global arena but also meets the just expectations and needs of the whole of humanity.

This accomplishment of the work of the High-level Panel and Amani Africa is reflected in the depth and scope of the issues canvased and the richness of the areas of reform identified in the report. The report thus makes it clear that reforming the multilateral system is a strategic imperative rather than a policy choice, both for Africa and the world at large. It also underscored the need both for addressing the structural flaws of the multilateral system and making it fit for the purpose of responding to current realities of the international order.

Accordingly, the report examines the sources and manifestations of the historical injustice Africa suffered in the multilateral system as it was designed and operated thus far including within the UN System. This includes the non-representation and underrepresentation of Africa in the permanent and non-permanent membership in the UN Security Council and the report outlines how this has dealt a legitimacy blow that can no longer be maintained without redress. It has thus articulated how the legitimacy and effectiveness of the UN, particularly its Security Council, can be restored by addressing this historic injustice on the basis of the Ezulwini Consensus as part of the Pact of the Future by affirming the commitment to treat Africa’s quest for permanent membership as a special case.

The report also highlighted and provided useful proposals on the need for an equitable and fair global financial and economic architecture and how to achieve robust cooperation to overcome the magnitude and interconnectedness of various challenges affecting the globe, such as climate change and cyber security and the necessity for the global community to organize the system in a way that caters for the needs and interests of various sectors of society, notably women, youth, and future generations.

In doing so, the report builds on AU’s Agenda 2063’s vision of Africa as a dynamic force in the international arena and the lessons from the historical processes that led to Africa’s marginalization. And it affirms Africa’s position as a bastion of multilateralism and a region with a major stake in and contribution to the reform of the multilateral process.

The report of the Panel also makes it clear that the contestation facing the world is not between dismantling the system and building a new one. The fact that there may exit those who espouse ideas of dismantling does not mean that they represent the majority of nations. From where Africa stands, the contestation facing the world is rather between the forces for reform and the forces of status quo. Considering that the status quo can no longer holds, it is clear that we need to reform the multilateral system and do so urgently. We cannot afford to move into the future with the attitude of the past.

Thus, in the stark choice between ‘reform and rapture’, as the UN Secretary General put it, the High-Level Panel is unequivocal in demonstrating that Africa’s choice is that of a reformed multilateral system that is inclusive, equitable and effective. As Africans, we have a responsibility to stand up and demand to be treated fairly and justly for the multilateral system to be legitimate and effective. If we do not speak up for ourselves, no one else will do it on our behalf.

The timing of this report could not have also been more fitting. It comes in the context of the various ongoing initiatives and political dialogues on the reform of the multilateral system, notably the proposal by the UN Secretary-General to convene the Summit of the Future, scheduled for next month. As such it helps to solidify and reinforce the articulation of common proposals by the Africa Group in the finalization of the Pact of the Future for whose negotiation Namibia is proud to serve as co-facilitator.

This accomplishment could not have been possible without the dedication and technical backstopping of our continental think tank Amani Africa Media and Research Services. I would like to particularly salute the Executive Director of Amani Africa, Dr Solomon Dersso, for his vision and leadership in the conceptualization, planning and implementation of this process with the commendable support of his team at Amani Africa. You deserve to be lauded for showing that Africa has the capacity for strategic thinking in shaping global discourse and policy action on multilateralism. Let the African intellectual capacity be used to the benefit of Africans and take Africa out of marginalization and its people out of poverty.

I also wish to thank the members of the High-level Panel for working together with Amani Africa for the great work you have done. Congratulations for a job very well done, by producing a report that makes all of us and I believe the entire Africa proud. In the same vein I thank Ambassador Jeroboam Shaanika, my representative in the High-Level Panel for his commitment and dedication to the task.

I urge all member states of the AU and the Africa Group in New York to draw on the recommendations contained in this report as they pursue the very pressing agenda for the reform of the multilateral system to effectively respond to Africa’s needs and interests and make it fit for the challenges of the 21st century and beyond.

The content of this article does not represent the views of Amani Africa and reflect only the personal views of the authors who contribute to ‘Ideas Indaba’

Open Session on Protection of Journalists and Access to Information in Situations of Armed Conflicts in Africa

Open Session on Protection of Journalists and Access to Information in Situations of Armed Conflicts in Africa

Date | 1 September 2024

Tomorrow (2 September), the African Union (AU) Peace and Security Council (PSC) will convene its 1230th session focusing on the Protection of Journalists and Access to Information in Situations of Armed Conflicts in Africa.

The Permanent Representative of Cameroon to the AU and Chairperson of the PSC for the month of September 2024, Churchill Ewumbue-Monono, will deliver opening remarks followed by Bankole Adeoye, AU Commissioner for Political Affairs, Peace and Security (PAPS). It is anticipated that Ourveena Geereesha Topsy-Sonoo, Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Expression and Access to information in Africa of the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights will make a presentation alongside Omar Faruk Osman, President of the Federation of African Journalists (FAJ) as well as Lydia Gachungi, UNESCO Regional Adviser on Freedom of Expression and Safety of Journalists. A representative from the ICRC is also expected to make a statement.

As highlighted below, while there were sessions that raised aspects of the issues expected to feature during this session, this is the first time the PSC is considering this theme as framed for this session. This open session coincides with the 10th anniversary of the International Day to End Impunity for Crimes against Journalists (IDEI). As it’s to be recalled, in 2013, during its 70th plenary meeting, the UN General Assembly adopted Resolution 68/163 in which it decided, on page 3, to, among other things, ‘…proclaim 2 November as the International Day to End Impunity for Crimes against Journalists.’ In this regard, to commemorate this anniversary, the AU and UNESCO are jointly planning to hold a global conference in Addis Ababa from 6 – 7 November 2024 under the theme of ‘Safety of Journalists in Crises and Emergencies.’ 28 September 2024 on the other hand, will also mark the International Day for Universal Access to Information (IDUAI) as decided during the 74th UN General Assembly, in October 2019. During its commemoration in 2021, the AU reiterated its commitment to promote the right of access to information despite the challenges faced at all levels.

Within the framework of the AU, one of the entities that has carried out various initiatives for the protection of journalists and access to information is the Banjul-based AU’s human rights body, the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights (ACHPR). Consistent with AU’s strategic plan, Agenda 2063, specifically Aspiration 3 and 4 which speak of “An Africa of good governance, democracy, respect for human rights, justice and the rule of law’’ and “A peaceful and secure Africa’’, respectively, and Article 9 of the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights, the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights (the African Commission) during its 67th Ordinary Session held from 13 November to 3 December 2020, adopted the ‘Resolution on the Safety of Journalists and Media Practitioners in Africa’. This resolution builds on the ACHPR’s Declaration of Principles on Freedom of Expression and Access to Information in Africa (the Declaration). This declaration provides a framework for African countries to follow as it contains establishments and principles for anchoring the rights to freedom of expression and access to information in conformity with Article 9 of the African Charter which guarantees individuals the right to receive information as well as the right to express and disseminate information. The Model Law on Access to Information, the ACHPR adopted in 2013, provides specific guidelines for African countries to fulfill their legal obligations under the African Charter regarding the right of access to information. Reports have further indicated that as of 2024, 29 African countries have adopted Access To Information (ATI) laws, while 26 others have yet to have the ATI law in Africa.

While journalists operating in conflict areas face inherent dangers, they are more vulnerable to direct violence as conflict parties seek to impose control on what is reported during conflicts. Thus, despite the provision of certain protection that is accorded to journalists under the international humanitarian law (IHL), such as immunity from military attacks and prisoner of war status for those accompanying armed forces, these protections are not always respected and journalists continue to face a wide range of threats, including censorship, harassment, arbitrary detention and even killings.

Recent reports indicate a rise in journalist killings in conflict-affected countries, reversing a previous trend of declining violence against media professionals. Although countries in conflict are not among the top countries with the worst records in the treatment of journalists as recorded in the Press Freedom Index in Africa 2022-2024, situations in which incidents of violence including the killing of journalists have been reported include the Sahel, Cameroon, DRC, Nigeria, Somalia, South Sudan and Sudan among others. Incidents of attacks and violence on media practitioners and journalists have also been reported in recent protests staged in Kenya and Nigeria. In Somalia, in the course of 2023, a report from the Somali Journalists Syndicate (SJS) documented numerous violent attacks, threats, and instances of persecution against media workers in the country. Somalia is widely regarded as one of the most dangerous places for journalists to work.

It is worth noting that women journalists and media practitioners face much higher levels of danger on account of the gendered nature of conflicts and crises. Apart from compounding the already small number of women media practitioners, such a gendered nature of attacks on women journalists has even greater adverse consequences in terms of giving voice to and capturing the disproportionately higher levels of dangers that women and girls are exposed to in conflict settings. In addition to these, the stigmatisation and stereotypical portrayal of women in conflict and crisis reporting, lack of women-owned media, underrepresentation of women in leadership roles, unethical reporting practices, and a failure to engage with survivors of violence, especially women and girls are more examples of challenges of journalism in the gender-inclusivity context. As it is to be recalled, the PSC during its 635th meeting held on 20 October 2016, dedicated to the theme ‘The role of the media in enhancing accountability on women, peace and security commitments in Africa’, stressed the need for, among other things, ‘…media reporting to be context-sensitive, as well as to take into consideration existing gender and power relations.’ This was followed by the launch of the Network of Reporters on Women, Peace and Security jointly by the AU Commission and UN Women on 21 October 2016, an initiative to recognise media as a key partner in advancing the women, peace and security agenda.

Taking note of the growing challenges of misinformation and disinformation as well as hate speech in the context of new digital technologies and the acuteness of these challenges in crisis and conflict settings, the session will underscore the importance of the protection of journalists and factual reporting. In the same context, the session is expected to reflect on the positioning, status and treatment of new forms of media namely bloggers, vloggers, content creators, influencers and a myriad of new media actors in the collection, treatment and diffusion of information in crisis contexts and emergencies. In this context, on 4 August 2022, PSC’s 1097th session dedicated under the theme of ‘Emerging Technologies and New Media: Impact on Democratic Governance, Peace and Security in Africa,’ highlighted ‘the need for the AU Commission to comprehensively and systematically address the immediate issues that arise from emerging technologies and new media, including the use of such emerging technologies and new media by actors engaged in terrorism and organised crime, the misuse of social media for propagation of hate, and the use of such technologies for surveillance, repression, censorship, online harassment and orchestrating cyber-attacks.’ Moreover, the session requested ‘the AU Commission in collaboration with relevant stakeholders to undertake a comprehensive study on Emerging Technologies and New Media: Impact on Democratic Governance, Peace and Security in Africa and the policy options available for harnessing the advantages and for effectively addressing the security threats associated with the use of these technologies and new media in Africa, based on available resources and to report back to Council.’

While there are six ‘Group of Friends for the Safety of Journalists’ globally, there is none in Africa. The six Group of Friends have been formed by permanent missions at the UN Secretariat in New York, UNESCO in Paris, OHCHR in Geneva, the Organisation for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) in Vienna, the Council of Europe (CoE) in Strasbourg and the Organisation of American States (OAS) in Washington. As such, tomorrow’s session may serve as an opportunity for the establishment of the Group of Friends for the Protection of Journalists in Africa, building on the Network of reporters on Women, Peace and Security launched in 2022 as noted above.

The expected outcome of the session is a communiqué. The PSC may express concern over the plight of journalists and other media practitioners in active conflict situations. In this regard, it may stress the important role that the media can play as an agent of peace through factual and professional reporting. The PSC may commend the rich jurisprudence and elaboration of soft laws on freedom of expression, access to information and the protection of journalists by the ACHPR and urge AU member States to draw on and respect these soft laws and the decisions of the ACHPR. The PSC may further stress the need for member states to create an enabling environment for media including through the adoption and implementation of the law on access to information in accordance with the Model Law as a critical step for enabling journalists and media practitioners to play their role of informing the public and providing factual information critical to policy making including factual information and reporting critical to the planning, designing and implementation of initiatives for peace and for fighting misinformation, disinformation and hate speech, thereby contributing to the achievement of Agenda 2063 and the goal of silencing the guns in Africa by the year 2030. The PSC may also call on AU member states to further strengthen their legal frameworks, combat impunity against journalists and guarantee the safety and security of media personnel. It may also reiterate its 635th session on the need for media reporting to be context-sensitive, as well as to take into consideration existing gender and power relations. PSC may also call for the adoption of targeted measures for the protection in particular of women journalists and media practitioners considering the disproportionately higher level of risk facing women media practitioners and their small number. The PSC may also call for the formation of a ‘Group of Friends for the Safety of Journalists in Africa’ similar to other continents, with the objective of enhancing multilateral cooperation, preventing violence, protecting journalists at risk, prosecuting perpetrators and creating a safe environment for media workers. The PSC may also call on all member states, which have not yet done so, to sign and ratify the AU Convention on Cyber Security and Personal Data Protection (Malabo Convention).

Monthly Digest on The African Union Peace And Security Council - July 2024

Monthly Digest on The African Union Peace And Security Council - July 2024

Date | July 2024

During Angola’s chairmanship in July, the African Union (AU) Peace and Security Council (PSC) planned to conduct five substantive sessions, one informal consultation, and a field mission to Mozambique. There were two changes to the Provisional Programme of Work (PPoW) for the month.

Of the five sessions, two were dedicated to addressing country-specific situations. The remaining three sessions, along with the informal consultation, focused on thematic matters. During the month, except for one ministerial-level session, all the sessions were held at the ambassadorial level.

Provisional Program of Work of the PSC for the Month of September 2024

Provisional Program of Work of the PSC for the Month of September 2024

Date | September 2024

In September, the Republic of Cameroon will assume the role of Chair of the Peace and Security Council for the month. The month’s Provisional Programme of Work (PPoW) includes five substantive PSC sessions and two field missions. Four substantive sessions will occur on thematic issues while one substantive session and two field missions will address country-specific situations. In addition to its field mission, members of the Council will partake in several bilateral and multilateral engagements for the month, most notably the 79th United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) where the major highlight is the Summit of the Future.

The first session of the month, scheduled for 2 September, will focus on the Protection of Journalists in Conflict Situations in Africa. This session marks the Council’s inaugural endeavour to address the protection of journalists in conflict situations. The session is prompted by the rising number of journalists trapped in war which is exemplified in the case of the war in Sudan where reports on the targeting and attacks on journalists by both of the conflict actors are ostensible. The session is an opportune moment for the Council to address the needs of journalists in the context of conflict.

During the second week of September, the Council will undertake a field mission to the Central Africa Republic (CAR) between 9-11 September. The field mission will commemorate African Amnesty Month, which has taken place every September since 2017 as part of AU’s flagship project on Silencing the Guns. During the last commemoration, the Council undertook a field mission to Maputo, Mozambique which focused on lessons learned from Mozambique on Disarmament Demobilisation and Reintegration (DDR). In addition to the commemoration of Amnesty Month, the Council will also undertake consultations with the CAR government as a follow-up to its recent session held in July where the Council deliberated on the status of the implementation of the Political Agreement for Peace and Reconciliation in CAR (PAPR-CAR) and the preparation for local elections. It may be beneficial for the Council to use this engagement as an opportunity to identify dedicated support to the CAR for bridging the gap and facilitating the minimum consensus necessary for an inclusive and participatory electoral process for local elections.

Upon completing a field mission to the Central African Republic (CAR), the Council will conduct another field visit to Gabon. During this visit, the Council will engage with the transitional government to discuss the process of returning to constitutional order. This session is particularly important as it coincides with the one-year anniversary of the military coup in Gabon on August 30, 2023. The transitional government has taken some measures to facilitate a return to constitutional order, such as launching the National Dialogue process in April 2024 and establishing a transitional timeline. Additionally, the Council will consult with the regional decision-making body of ECCAS. This is similar to the consultation the PSC held in April with the ECOWAS Council.

On 16 September Civil-Military Relations and Conflict Management in Africa. The PSC over the past two years has consistently scheduled a session on civil-military relations as a factor for peace and security in Africa’ in 2022 and a session on Code of Conduct on the Civil-Military-Relations in Africa at the Military Staff Committee in 2023, although the session in the end did not materialise despite having been scheduled. The session will provide an opportunity for the Council to have dedicated attention to this crucial matter.

On 18 September, the PSC will host an open ambassadorial-level session on ‘Disaster Management in Africa: Nexus between Climate Change, Peace, and Security in Africa’. This session comes at a time when African member states are increasingly engaged in discussions about the impact of climate change and the rising number of disasters on the continent over the past decade. There has been a noticeable increase in natural disasters across Africa, ranging from the devastating impact of Storm Daniel in Libya, which resulted in the deaths of over 4,000 civilians, to the consistent occurrence of cyclones in southern Africa, particularly Mozambique, as well as an increasing number of floods in East Africa. These events highlight the growing concern around natural disasters in Africa. It is crucial for the Council to address the root causes and find sustainable solutions to the challenges posed by natural disasters. The Council has not yet requested the identification of mitigation strategies, which is an essential step towards addressing this issue. During the PSC’s 1043rd session on ‘Addressing Disaster Management Issues in Africa: Challenges and Perspectives for Human Security’, concrete measures were not taken to address the impact of natural disasters on human security. Considering the increasing number of natural disasters since the last session, it is vital for the Council to use this session as an opportunity to identify mitigation measures that member states can take to protect their citizens in the face of the growing likelihood of natural disasters.

On the margins of the Summit of the Futures, on 25 September, the PSC will have a session on new security threats in Africa and the future of the PSC at the ministerial level, as part of the anniversary of the PSC @20. This will take forward the issues identified during the summit level 20th anniversary of the PSC held in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania on 25 May and build on the Dar es Salaam Declaration on the anniversary.

As the last session of the month, the PSC will receive an update on the situation in South Sudan on 30 September. Over this year, the PSC has engaged the situation in South Sudan by undertaking a field mission and holding its 1219th session to consider the adoption of the Report of its field mission to South Sudan. Key elements that may be relevant for the PSC to consider during its session include the PSC’s request for the AUC Chair to support South Sudan in Disarmament, Demobilization and Reintegration (DDR) and Security Sector Reform (SSR); the training deployment of Necessary United Force (NUF) and the Councils request for the AUC to provide technical support and coordinate with relevant actors in mobilising technical and financial assistance as South Sudan as it prepares for its upcoming elections.

In addition to the substantive sessions and activities of the PSC, the program of work for the month also encompasses the meetings of the PSC subsidiary bodies. The Committee of Experts (CoE) is expected to continue their preparatory meeting on the 18th Annual Joint Consultation between the PSC and UNSC, which has been consecutively tabled on the PSC agenda since July. The Military Staff Committee will also convene on 5 September to engage with the African Peace Support Trainers Association.