Will the possible end of the AU Mission in Somalia open new opportunities for peace?

Will the possible end of the AU Mission in Somalia open new opportunities for peace?

Date | 23 May 2025

Zekarias Beshah

Senior Researcher, Amani Africa

Solomon Ayele Dersso, PhD

Founding Director, Amani Africa

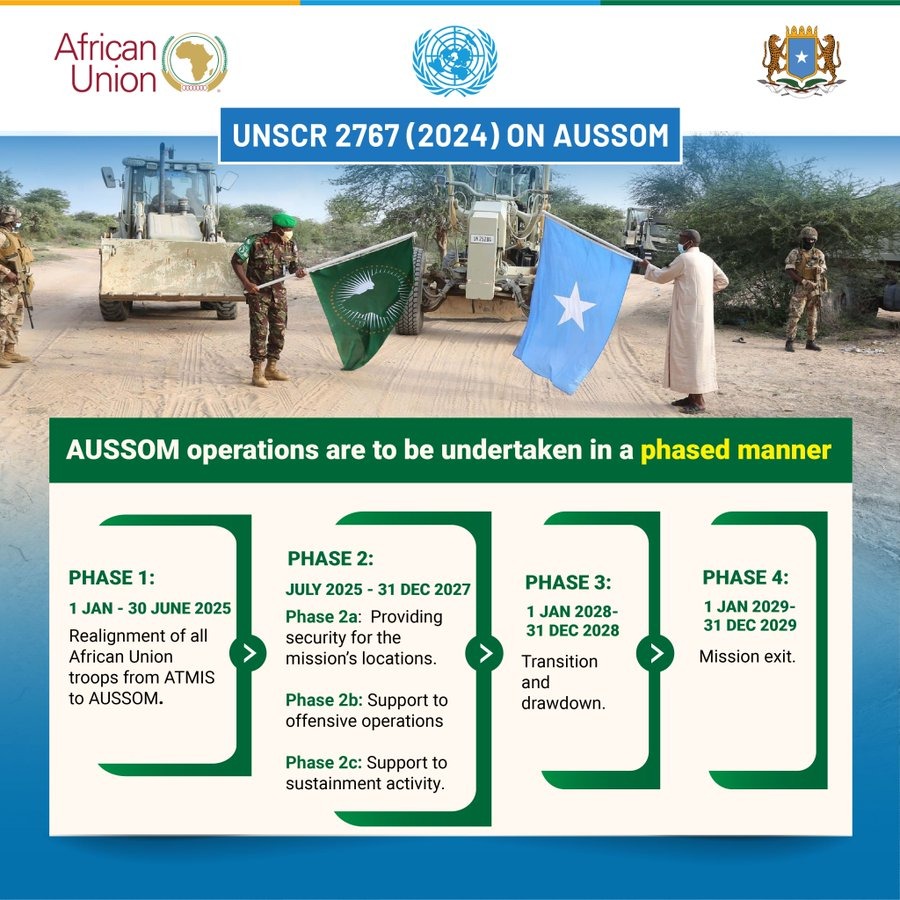

The African Union (AU) Support and Stabilisation Mission (AUSSOM) became de jure operational on 1 January 2025 under huge financial deficits and without a clear financing modality. The timing of AUSSOM becoming operational also coincided with the surge in the attacks and territorial gains of Al Shabaab in recent months. While the changing security dynamics prompted the summit of troop contributing countries (TCCs) hosted by Uganda on 25 April 2025 to call for the mobilisation of an additional 8000 troops, the growing financial deficit of the mission and the lack of its financing model remain unchanged.

The financing hole facing AUSSOM

The estimated budget for AUSSOM from July 2025 to June 2026 stands at $166.5 million, based on the troop reimbursement rate of $828, according to the UN Secretary-General’s report to the Security Council dated 7 May 2025. However, the funding challenge extends beyond this figure—it includes the substantial debt inherited from its predecessor, ATMIS. The total urgent cash requirement to settle ATMIS liabilities for the period January to June 2025 is reported at $92 million. In addition, outstanding arrears owed to TCCs from 2022 to 2024 amount to $93.9 million, including Uganda ($34.5 million), Kenya ($15.7 million), Ethiopia ($17.2 million), Djibouti ($8.3 million), and Burundi ($18.1 million).

So far, committed funding amounts to only $16.7 million, comprising contributions from China ($1 million), Japan ($3 million), the Republic of Korea ($1.6 million), and the AU Peace Fund’s Crisis Reserve Facility ($10 million). With Resolution 2719 now off the table as a viable funding option, the AU faces the daunting task of mobilising the needed funds from alternative sources. The European Union (EU), which has been the single largest direct contributor to AU mission in Somalia, providing nearly €2.7 billion since 2007, shows little appetite to sustain its past commitments, given shifting geopolitical priorities. While the EU may still commit some funds, it is unlikely to fill the gap. Contributions from non-traditional donors also appear limited, as seen from the modest pledges by China, Japan, and South Korea. (For further analysis of AUSSOM’s funding challenges and related discussions, see Amani Africa’s ‘Insights on the PSC’ here and here.)

The promise that failed to materialise

Despite the decision of the UN Security Council (UNSC) in its Resolution 2767 that Resolution 2719 could be used as the main source of predictable financing of AUSSOM upon UNSC authorisation on 15 May 2025, the UNSC meeting held on 12 May was unable to adopt the resolution authorising the use of Resolution 2719. This has shattered AU’s preferred funding model as the only viable path for sustaining AUSSOM, putting the very continuity of the mission in its current form in serious question.

Since the adoption of Resolution 2719, the AU has consistently advocated for the resolution’s first activation in support of the post-ATMIS security arrangements, which eventually took shape as AUSSOM. Indeed, the AU-UN joint report submitted to the UNSC on 26 November 2024 proposed the hybrid implementation of resolution 2719 as the only solution for AUSSOM. However, this effort faced opposition from the United States from the outset, with Washington arguing that Somalia was not a suitable test case for the application of the resolution. It was in this context that the Security Council held closed consultations on 12 May 2025. With the U.S. maintaining its position that Somalia is not the best place to trigger resolution 2719, the Council was unable to confirm the Secretary-General’s request as envisaged under paragraph 39 of UNSC Resolution 2767.

A search for alternative funding?

No doubt, much of the attention would now shift to finding alternative sources of funding. Indeed, efforts are underway to convene an international donor pledging conference in Doha, Qatar, by the end of this month to rally support for AUSSOM and Somalia. The conference, initially planned for late April, has already been postponed to the end of May. With no confirmed date, it remains uncertain whether there is genuine interest in convening the event, and even if it does happen, whether it will yield the kind of sustainable funding the mission desperately needs.

Though it may be possible to cobble together enough funding to keep AUSSOM running for a few more months, doing so in dribs and drabs is not sustainable. This approach has already plunged the AU into a perpetual financial crisis with serious implications for the mission’s effectiveness and credibility. Indeed, it is not clear if a success in finding such alternative sources can do more than postpone the inevitable for a few months. After more than 18 years of deploying its longest, most expensive, and deadliest mission in Somalia, the time may have come to consider an exit. This apparent inevitability presents a much-needed opportunity for thinking about other options than an AUSSOM model of pursuing peace in Somalia, with Somalia’s political and social actors forced to take their acts together for mobilising the requisite level of collective leadership and responsibility for tackling the security challenge facing Somalia.

Also, a search for a different approach to peace in Somalia?

While ending AUSSOM is not risk free, it is not totally bad either. It could open the door to two possible security arrangements: bilateral security partnerships or an ad hoc regional military alliance to counter Al-Shabaab—something akin to the Multinational Joint Task Force (MNJTF) in the Lake Chad Basin.

Whatever shape post-AUSSOM security takes in Somalia, ending the mission can also have an upside in terms of ensuring the primacy of political and diplomatic strategy. Two aspects in particular deserve attention.

First, in the military and political dimensions of the equation for finding a lasting solution to the security crisis facing Somalia, the weakest link remains to be the political dimension of the equation. Rather than enabling Somalia’s political and social forces to assume greater agency and responsibility in adopting a political roadmap backed by all sectors of society for resolving the conflict, the perpetual presence of AU missions created dependency and externalisation of this responsibility. Despite some progress registered over the years in this respect, Somali political actors remain locked in protracted infighting both at the Federal level and between the Federal Government of Somalia (FGS) and the Federal Member States (FMS). The fracturing of the political landscape continues to deepen, with the National Consultative Council members turned into members of a new political party of President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud. Ending the mission could inject much-needed pressure on Somali political leaders to end their complacency and focus their attention to working collectively and achieve political cohesion.

Second, it may pave the way to imagine the resolution of Al-Shabaab’s insurgency beyond and above military solutions underwritten by AU peace support operations. The ultimate objective of any peace operation is to create the space for a political solution. Over the last 18 years since the first deployment of the African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM) in March 2007, the AU’s military engagement in the country has made significant security gains over Al-Shabaab, but these gains cannot be sustained with indefinite peace operations. As argued by the UN Under-Secretary-General for Peacekeeping Operations, Jean-Pierre Lacroix, ‘…whatever form a peace operation takes, to be effective in the long run it must be anchored in and contribute to an overarching political solution.’ Such a political solution continues to delude Somalia. Eighteen years of AU mission in Somalia played critical role in liberating territories under Al Shabbab control and in expanding the space for the operation of Somalia’s fledgling institutions. It was pointed out in 2010 that rather than being an instrument for advancing the implementation of a political process, the AU mission became ‘the primary means of international engagement in Somalia, taking the place of an absent political process.’ Whatever progress that has been made in the political front remains inadequate and AU’s mission continues to be used as the primary instrument in the quest for peace. The result is that the military approach has come to take primacy and the prolonged presence of AU missions being used to perpetually short change the investment in a political strategy.

The end of ASUSSOM could force a much-needed rethinking for shifting the focus towards ensuring the primacy of politics in the search for resolving the crisis in Somalia. It could force Somalia’s political and social forces to take far greater interest in and invest more resolutely in prioritizing national reconciliation and inclusive political settlement, thereby shifting away from the protracted infighting that characterizes the Somalia political landscape. Similarly, it could give the international community the opportunity to play a more supportive role by seizing the space AUSSOM’s exit creates for prioritizing its investment in such a political process.

While the risk associated with AUSSOM’s end should be managed carefully, this also seems to be an opportune moment to change course and try new approaches rather than clinging to a model whose role is for managing rather than resolving the crisis facing Somalia.

The content of this article does not represent the views of Amani Africa and reflect only the personal views of the authors who contribute to ‘Ideas Indaba’

Consideration of the Emergency Situation in Libya

Consideration of the Emergency Situation in Libya

Date | 22 May 2025

Tomorrow (23 May), the African Union (AU) Peace and Security Council (PSC) is scheduled to convene its 1280th session on the situation in Libya.

Following opening remarks by Ambassador Harold Saffa, Permanent Representative of Sierra Leone to the AU and Chairperson of the PSC for May, Bankole Adeoye, AU Commissioner for Political Affairs, Peace and Security (PAPS), is expected to deliver a statement. The Special Representative of the Chairperson of the Commission for Libya, Ambassador Wahida Ayari, is also likely to make a statement. If previous practice is guidance, the Special Representative of the UN Secretary-General and the Head of the UN Mission in Libya, Hannah Tetteh, may also address the PSC.

The last time the PSC considered this agenda item was in November 2024, during its 1244th meeting. The PSC reiterated ‘AU’s full support for the Permanent Ceasefire Agreement of 23 October 2020’ and reaffirmed ‘the resolute commitment and readiness of the AU to continue to support Libya in addressing its crisis, in line with AU’s principles and instruments.’ Other than this session, the only engagement of the AU involved a high-level visit in October 2024 by a delegation comprising Mauritanian President and AU Chairperson for 2024, Mohamed Ould Ghazouani, the then AU Commission Chairperson Moussa Faki Mahamat and Congo’s Foreign Minister Jean-Claude Gakosso. The visit aimed to revive efforts to convene Libya’s long-delayed national reconciliation conference, which was initially scheduled for April 2024 but did not take place. Beyond the occasional effort focusing on the convening of national reconciliation, the attention given to the situation in Libya has been waning, with the PSC convening only one session. The field mission to Libya, envisaged in the PSC’s annual indicative programme, did not take place in 2024, just as it did not in 2023.

Tomorrow’s meeting comes following the assassination of a key militia leader, which has reignited violence in Tripoli, threatening the fragile 2020 ceasefire. The assassination of Abdel Ghani al-Kikli (aka ‘Gheniwa’) on 12 May 2025, a prominent militia leader of the Stability Support Apparatus (SSA), sparked intense clashes in Tripoli. The fighting involved rival militias, including the 444th Combat Brigade, with gunfire, drones and anti-aircraft weapons reported. The Interior Ministry declared a state of emergency, urging residents to stay indoors.

Such violent eruptions are not inseparable from the state of political and security division afflicting Libya. The country remains fractured by a relentless political division, its people caught in the crossfire of two rival administrations vying for power. In Libya’s capital, Tripoli, the UN-recognised Government of National Unity (GNU), led by Prime Minister Abdul Hamid Dbeibah, holds sway, striving to assert its legitimacy on the global stage. Meanwhile, in eastern Libya in Benghazi, the Government of National Stability (GNS) commands influence, bolstered by the House of Representatives (HoR) and Field Marshal Khalifa Haftar’s Libyan National Army (LNA). This division, rooted in years of conflict following the 2011 overthrow of Muammar Gaddafi, has left Libya in a state of recurrent political instability, institutional fragmentation and recurrent violence.

With both sides locked in a bitter struggle for dominance, the rivalry between the two sides and rival armed supporters has stifled the transitional process. Previous efforts to overcome this division have rather been unsuccessful. National elections, initially slated to bring reconciliation and a unified government, have been indefinitely postponed since 2021, mired in disputes over electoral laws and eligibility criteria. As oil fields – Libya’s economic lifeline – become ‘bargaining chips’ in the power struggle, foreign powers quietly back their preferred faction. The persistence of these conditions has deepened the nation’s woes, with ordinary Libyans bearing the brunt of economic instability, periodic violence and a fragmented state.

The Eastern Libya-based parliament was reported to have adopted a national reconciliation and transitional justice law in January 2025. In parallel, in February 2025, a Charter for Peace and Reconciliation was signed in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, on the sidelines of the 38th AU Summit. The Libyan parties that signed the charter included representatives from the Parliament, the High State Council, and representatives of presidential candidate Saif al-Islam Gaddafi, along with other Libyan dignitaries. Reflecting the persisting division in Libya, it was the head of the Presidential Council, Mohammed al-Menfi, who was present in Addis Ababa for the AU Summit, but did not sign the Charter. The Government of National Unity also did not send a representative to sign the reconciliation accord.

The UN remains the main actor in the Libyan peace process. Cognisant of this and following the departure of Abdoulaye Bathily from UN Support Mission in Libya (UNSMIL), the PSC, in the communiqué of its 1244th Session, underscored ‘the urgent need for the United Nations Secretary-General to appoint his Special Representative for Libya.’ On 24 January 2025, the UN Secretary-General António Guterres announced the appointment of Hanna Serwaa Tetteh of Ghana as his Special Representative for Libya and Head of the UNSMIL, succeeding Abdoulaye Bathily of Senegal, who served as Special Envoy and Head of UNSMIL until May 2024. Since her appointment, UNSMIL established a 20-member Libyan Advisory Committee, a diverse group of experts tasked with untangling the contentious issues blocking the path to elections. Comprising respected Libyan figures with expertise in legal, constitutional and electoral matters, the committee was designed to propose technically sound and politically viable solutions, building on frameworks like the Libyan Political Agreement, the Libyan Political Dialogue Forum (LPDF) Roadmap and the 6+6 Committee’s electoral laws. By 20 May 2025, after more than 20 meetings in Tripoli and Benghazi, the committee delivered a comprehensive report to UNSMIL, outlining four options to address critical disputes, including the linkage between presidential and parliamentary elections, candidate eligibility criteria, voting rights and the electoral appeals mechanism. This report, described by UNSMIL as a ‘launching point for a country-wide conversation,’ aimed to guide the next phase of a Libyan-led political process, with public consultations planned to foster inclusivity and national consensus. However, consensus remains elusive.

On 17 May, the AU Commission Chairperson, Mahmoud Ali Youssouf, issued a statement expressing deep concern over the armed clashes that broke out in Tripoli. While welcoming ‘the ceasefire and the return of cautious calm’, he emphasised the need for ‘demilitarising’ Tripoli. Calling for ‘national responsibility and engagement in a comprehensive political process to end Libya’s prolonged transition’, he urged all stakeholders to commit to ‘the National Reconciliation Charter signed in Addis Ababa.’ On the same day, the UNSC issued a Press Statement on the situation in Libya, expressing ‘deep concern at the escalation of violence in Tripoli in recent days, with reports of civilian casualties.’ The Security Council further ‘welcomed reports of agreed truces and called for these to be unconditionally respected and for a permanent ceasefire to be agreed.’

Despite the return of calm, on the political front, actions taken by the rival factions continue to escalate tension. The latest such development involved the announcement by the Head of the Presidential Council (PC) of several legislations that he said were adopted by the PC. While these legislations were rejected by some Libyan institutions, including some members of the PC and the speaker of the HoR, the Prime Minister of the GNU, Abdulhamid Debaiba, transmitted the legislations to the HoR and the High Council of State. Amid these developments, UNMSIL issued a warning against the risk of escalatory unilateral actions by political and security actors and urged them to refrain from taking steps that undermine the fragile situation in Libya.

As with previous sessions, tomorrow’s session is expected to discuss the recent armed clashes in Libya and the continuing political and institutional division impeding progress in the transitional process in the country. It is also expected that the PSC will get an update on developments around the reconciliation process and the status of and the follow-up to the Peace and Reconciliation Charter signed under the auspices of the AU. Also of interest for the PSC is receiving an update on the progress made in relocating the AU Liaison Office from Tunis to Tripoli, as directed by the AU Assembly at its 35th Ordinary Session.

The expected outcome of the session is a communiqué. The PSC may urge the various Libyan stakeholders to summon the leadership and the compromise required to end the prevailing political stalemate and instability in the country, which is undermining development and security. Council is also likely to reiterate that the Skhirat Agreement signed on 17 December 2015 remains one of the credible bases and frameworks for a lasting political solution for the Libyan crisis. Council may welcome the Libyan Reconciliation charter signed in Addis-Ababa on 14 February 2025. The PSC may request the AU to take steps to ensure that the Charter receives the support of all Libyan stakeholders and is adequately aligned with other initiatives in Libya for reconciliation and transitional justice. The PSC may call on external actors to end interference in the affairs of Libya and support the rivalry among contending Libyan actors. The PSC may also emphasise the importance of improved coordination, harmonisation and complementarity among the UN, the AU, the League of Arab States and the EU to prevent overlapping efforts and competing initiatives in support of Libyan peace.

Amani Africa’s prominent role in the global policy thinking on the future of peace operations

Amani Africa’s prominent role in the global policy thinking on the future of peace operations

Date | 19 May 2025

At a time when multilateral peace operations are at a crossroads, Amani Africa’s role has become prominent in shaping the global policy thinking on the future of peace operations, when, along with the Global Governance Institute (GGI) and the Berlin Center for International Peace Operations (ZIF), it fostered the establishment of the Global Alliance for Peace Operations (GAPO). The GAPO is made up of more than 60 global think tanks, research institutes and civil society organizations and more than 100 experts, who play leading role in the policy thinking and action for adapting peace operations for making them fit for the changing realities of the world. The website of GAPO is now also featured on Amani Africa’s website.

To avail rich and fresh perspectives to the intergovernmental deliberations during the 2025 UN Peacekeeping Ministerial in Berlin, Germany, together with GGI and ZIF, Amani Africa contributed to the coordination of the writing by members of GAPO of a compendium of eight policy papers (see here) and nearly 20 issue briefs (see here). These contributions reflect the diversity and richness of the membership of GAPO and its immense potential for shaping multilateral policy processes on international peace and security.

Along with ZIF and GGI, Amani Africa coordinated the convening on 12 May 2025 of the GAPO Symposium on Peace Operations, hosted at Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik (SWP) in Berlin, Germany just ahead of the Berlin Peacekeeping Ministerial. Solomon Dersso, Founding Director of Amani Africa, led the first session titled ‘The State of the World’ which, through the insightful interventions of Jenna Russo of International Peace Institute, Daniel Forti of International Crisis Group and Alexander Marschik, Ambassador of Austria to Germany and former Co-Chairperson of the IGN on UNSC Reform, depicted a clear picture of the fundamental changes and challenges affecting multilateralism and peace operations. The symposium highlighted the need for reforming peace operations as important part of the toolbox for international peace and security and explored diverse and rich ideas on how UN peacekeeping can be adapted and strengthened for it to continue to play critical role in advancing international peace and security.

Amani Africa also played various roles in the 2025 UN Peacekeeping Ministerial held on 13-14 May in Berlin, Germany at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Germany. Apart from attending the deliberations of the ministerial session that brought together more than 130 state delegates, Amani Africa was involved in various conversations during and on the side of the ministerial session. We also had the unique honor of being featured along co-coordinators of GAPO in hosting the sole exhibition stand at the Berlin Ministerial, showcasing our contributions to global policy discussion and action on peace operations.

As part of the Berlin Ministerial, Amani Africa’s Founding Director made a contribution as a speaker during the High-Level Panel on Partnerships, that featured senior representatives from the UN, AU, EU, and OSCE as well as Founder and Director of Confluence Advisory. The panel explored how to deepen and adapt the relationship of the UN with regional organisations with respect to peace operations, whether and how the role of regional organisations is changing vis-à-vis peace operations, the role of the UN in situations where regional or sub-regional organisaitons or coalitions of the willing lead peace operations, and how and when to operationalize Resolution 2719 on UN financing of AU-led peace operations.

Amani Africa acknowledges with appreciation the support and collaboration of the German Foreign Ministry, Embassy of Germany in Addis Ababa and the co-conspirators of GAPO, ZIF and GGI as well as all the institutions and experts who contributed to and form part of GAPO.

Second Annual Joint Consultative Meeting between the AUPSC and ECOWAS Mediation and Security Council

Second Annual Joint Consultative Meeting between the AUPSC and ECOWAS Mediation and Security Council

Date | 15 May 2025

Tomorrow (16 May), the African Union (AU) Peace and Security Council (PSC) is expected to convene its Second Annual Joint Consultative Meeting with the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) Mediation and Security Council (MSC), at the AU Commission in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

Following opening remarks by Harold Bundu Saffa, Permanent Representative of Sierra Leone to the AU and PSC Chairperson for May, the Chair of ECOWAS Mediation and Security Council is expected to make a statement. Mahmoud Youssouf, Chairperson of the AU Commission, may also address the session.

The PSC held its inaugural meeting with Regional Economic Communities/Regional Mechanisms (RECs/RMs) policy organs on the promotion of peace and security, focusing on harmonisation and coordination of decision-making processes and division of labour in May 2019. The joint communiqué of that meeting agreed to hold ‘annual joint consultative meetings, between the PSC and the RECs/RMs policy organs on peace and security issues, alternately in Addis Ababa and in the headquarters of the RECs/RMs, in rotation’ and to be ‘convened ahead of the mid-year coordination summit between the AU and RECs/RMs’. It took some years before the PSC acted on the convening of a consultative meeting with individual REC/RM policy-making organs similar to the consultative meeting it holds annually with the United Nations (UN) Security Council and the European Union (EU) Peace and Security Committee. The first such consultative meeting was held with the ECOWAS MSC on 24 April 202, when, as part of its April 2024 Programme of Work, the PSC undertook a field mission to Abuja, Nigeria, for the High-level African Counter Terrorism Meeting.

The Inaugural Joint Consultative Meeting with ECOWAS MSC zeroed in on the dire situation in West Africa, the Sahel and the Lake Chad Basin, where terrorist activities have wreaked havoc on communities and derailed development. The Joint Communiqué voiced deep alarm over the surging insecurity fueled by terrorism and extremism. The two Councils called for robust counter-terrorism strategies, backed by substantial funding and resource mobilisation to bolster regional and continental peace operations. They emphasised the need for revitalisation of existing security frameworks, such as the Nouakchott and Djibouti Processes, the ECOWAS Plans of Action Against Terrorism, the Accra Initiative, and the Multinational Joint Task Force of the Lake Chad Basin. Beyond military measures, the meeting highlighted the necessity of tackling the root causes of terrorism – poverty, unemployment, political instability and social inequality.

Since then, a meeting of the Nouakchott process was held in November 2024 in Dakar, Senegal. Convened with the support of the Committee of Intelligence and Security Services of Africa (CISSA) and the Government of the Republic of Senegal, the meeting sought to ‘enhance coordination, information and intelligence sharing, and joint operations in the fight against terrorism in the Sahel-Sahara region.’ The meeting (which saw the participation of ECOWAS, MNJTF, Executive Secretariat of the Accra Initiative and the Fusion and Liaison Unit (UFL) of the Sahel countries) brought together the heads of intelligence services of the Sahel-Sahara countries, particularly member states of the Nouakchott Process and the Accra Initiative, namely Algeria, Benin, Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana, Guinea, Libya, Mauritania, Nigeria, Senegal, and Togo. It is of interest to both the PSC and the ECOWAS MSC to receive an update on the outcome of this meeting and how to build on the outcome for developing and implementing concrete policy action to stem the tide of conflicts involving terrorist groups in the Sahel and West Africa.

The other issue that the inaugural meeting focused on was the instability military coups induce and the governance deficits fueling unconstitutional changes of government (UCG), which has affected most prominently the ECOWAS region. They welcomed the creation of the PSC Sub-Committee on Sanctions to oversee UCG-related decisions. Against the background of the growing pressure for speeding up the process towards lifting suspension of countries in transition including the recent return of Gabon to the AU fold in full, tomorrow’s consultative meeting is also expected to discuss how the AU and ECOWAS develop a joint strategy and engage more actively to negotiate and agree on the parameters of the process for the restoration of constitutional order in Burkina Faso, Guinea, Mali and Niger while having regard to the specificities of each situation.

While they stressed the importance of joint mediation without clarifying the modalities for translating that into action, this requires that they change their institutional culture and the conceptual parameters governing their role in peace and security. First, they need to recognise that many of the challenges facing the region cannot be addressed by any one institution and need the role of both the AU and ECOWAS, having regard to the terms of Article 16 of the PSC Protocol. Second, conceptually, instead of subsidiarity and the competition it induces, they should embrace complementarity. Instead of comparative advantage, they should work on the basis of cumulative advantage.

In terms of modalities, the meeting agreed on mechanisms to ensure coherence and complementarity, including annual joint consultative meetings, frequent interactions between chairpersons and swift communication of decisions. They also proposed joint field missions, retreats, staff exchanges and the establishment of focal point teams. There is no indication that they have started to operationalise these proposed areas of action for deepening their close working relationship.

Given that this second consultative meeting coincides with the 50th anniversary of ECOWAS, it is expected that the 50-year journey of ECOWAS, particularly in the realm of peace and security, democratic governance and constitutional rule, as well as regional integration and the challenges facing them, are expected to feature during the session. Of immediate concern will be the withdrawal of the Alliance of Sahel States (AES) from ECOWAS. Indeed, during the inaugural session, a particularly pressing issue was the announcement of Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger for withdrawal from ECOWAS. The two Councils urged continued engagement with these states to preserve regional stability, referencing the ECOWAS Extraordinary Summit communiqué of 24 February 2024, and Article 91 of the 1993 ECOWAS Revised Treaty, which outlines withdrawal procedures. On 29 January 2025, the withdrawal of these countries from ECOWAS took effect. This notwithstanding and in a commendable step, ECOWAS expressed commitment to preserving crucial privileges for citizens of these countries, including recognition of ECOWAS-branded documents, trade benefits under ETLS, visa-free movement rights, and support for ECOWAS officials from these nations.

Building on the maintenance of the relations, apart from commending ECOWAS on avoiding complete severance of the relationship, the consultative meeting may consider how best to support AES states in their quest for containing terrorism and restoring stability. Relatedly, of interest for both the AU and ECOWAS is also how to reverse the instrumentalisation of tensions and instability for settling geopolitical scores by external powers attempting to reduce the region into a theatre of geopolitical rivalry.

As with the first consultative meeting, the expected outcome is a Joint Communiqué. The meeting is expected to welcome the institutionalisation of the consultative meeting by implementing the joint communique of the inaugural meeting that decided the convening of the meeting on an annual basis. The PSC and the MSC are also expected to reiterate their commitment to deepen closer working relationship by implementing the conclusions of the inaugural consultative meeting. They may also welcome the steps taken in implementing the joint communique, particularly the convening of the Nouakchott process with the participation of ECOWAS and its member states. They may ask AU and ECOWAS Commissions to develop workstreams and focal points for operationalising the parts of the joint communique that are yet to be implemented. The PSC and the MSC may also underscore that most of the challenges in the region demand joint action and the collective weight of the AU and ECOWAS. The two sides may underscore the importance of ECOWAS as a key pillar of regional integration in the ECOWAS region and the need for revitalising ECOWAS and safeguarding the progress it registered during its 50-year journey. PSC and the MSC may also commend the measures ECOWAS adopted for keeping its door open for Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger, including by sustaining the benefits of ECOWAS membership to the citizens of the three countries.

Open Session on Organised Transnational Crime, Peace and Security in the Sahel Region

Open Session on Organised Transnational Crime, Peace and Security in the Sahel Region

Date | 13 May 2025

Tomorrow (14 May) the African Union (AU) Peace and Security Council (PSC) is scheduled to convene its 1279th session as an open session on Organised Transnational Crime, Peace and Security in the Sahel Region.

Following opening remarks by Ambassador Harold Saffa, Permanent Representative of Sierra Leone to the AU and Chairperson of the PSC for May, Bankole Adeoye, AU Commissioner for Political Affairs, Peace and Security (PAPS), is expected to deliver a statement. Briefings are also expected from representatives of the Committee of Intelligence and Security Services of Africa (CISSA) and the AU Mechanism for Police Cooperation (AFRIPOL).

Despite the Council’s decision in 2019, during its 845th session, to institutionalise an annual session on Transnational Organised Crime (TOC) as a standing agenda item, the last time the Council convened a session dedicated to the theme was in May 2022 during its 1082nd session. However, the Council had consistently shown concern over the rise of transnational organised crime in Africa in several sessions on conflict-specific situations and on thematic sessions, particularly those on terrorism, illicit economy and the proliferation of small arms and light weapons. The Council has also acknowledged the convergence between TOC and terrorism. During its 1237th session, convened to consider the report of the AU Commission on combating terrorism in October 2024, the Council noted with deep concern the growing linkages between TOC and terrorism and called for the strengthening of international cooperation.

Tomorrow’s session is of particular importance given the accelerating pace at which organised criminal networks are expanding their operations across Africa and some countries and regions have become major sites of TOC. These include notably the Sahel and the Lake Chad basin. According to data from the Africa Organised Crime 2023 Index, countries in these regions exhibit some of the highest levels of organised criminality on the continent above the continental average of 5.25. Such is the case in Nigeria (7.28), Sudan (6.37), Cameroon (6.27), Mali (5.93), Burkina Faso (5.92), Niger (5.70) and Chad (5.50). Beyond trafficking in arms, TOC in these regions and beyond manifests in multiple forms: trafficking in narcotics, people, and fuel; cybercrime; and the illicit exploitation of natural resources, such as gold.

Another dimension of TOC is its deepening entanglements with terrorism, insurgency and broader instability. And the growing convergence between TOC and terrorism is increasingly evident in various parts of Africa, but more so in the Sahel and Lake Chad basin, which are most affected by terrorism. While it does not account for it, TOC contributes to and is aggravated by the standing of the Sahel as the region that has become the epicentre of global terrorism. Illicit arms and weapons proliferation and trade is one example of TOC affecting the Sahel. In this context, the TOC and conflicts involving terrorist groups feed into each other, as criminal economies provide financial lifelines to extremist groups, while terrorist actors offer protection and enforcement mechanisms to illicit traders. These mutually reinforcing relationships allow both sets of actors to thrive in environments of weak state control, porous borders, and pervasive governance deficits.

The political economy of TOC goes beyond simply criminal economies in regions like the Sahel. It also creates an environment in which it is used as an informal survival strategy for marginalised communities, where state presence is weak and employment and livelihood opportunities are scarce. A 2024 UNODC report underscores this feature of TOC in the Sahel, both as intensifying violence and serving as a critical source of livelihood for economically marginalised communities. By distributing the benefits of illegal markets, non-state armed groups often gain accommodation from local communities, further entrenching their influence and ability to perpetuate the cycle of insecurity. Firearms trafficking, in particular, has played a catalytic role in triggering conflict across the Sahel. Additionally, the UNODC report notes that organised criminal networks provide financial and human resources to armed groups, thereby prolonging conflicts. Illicit economies are central to sustaining violence, as revenues are either directly or indirectly reinvested in weapons and logistical support, strengthening the operational and economic resilience of armed groups.

Given the role of unregulated borders in facilitating TOC, the other issue to be addressed in tomorrow’s session is the institutional weaknesses at the national level that create the vacuum for the emergence and expansion of TOC. This draws attention to some of the major underlying causes, including spaces with weak presence of state institutions and porous borders. Apart from addressing state fragility and expanding legitimate local structures of governance, this highlights the need for strengthening border control capacities through training, technology transfer, and joint operations.

In addition to receiving updates and reflecting on trends in TOC in the Sahel during the past few years and its intersection with insecurity and conflict, tomorrow’s session serves to follow up on PSC’s earlier engagements on the subject. In its communiqué from its 1082nd session, the PSC had requested AFRIPOL to work in collaboration with the International Criminal Police Organisation (INTERPOL) and the Committee of Intelligence and Security Services of Africa (CISSA) to develop two databases; one on persons, groups and entities involved in Transnational Organised Crimes, including Foreign Terrorist Fighters; and another regional database for guiding member states and RECs/RMs on their policy interventions for Transnational Organised Crimes. The PSC also requested AFRIPOL and INTERPOL to produce in-depth research on ‘regional information papers in the fight against transnational organised crime’. Given the two-year lapse, tomorrow’s session will provide an opportunity for the PSC to assess progress on these mandates and renew calls for institutional synergy. Also of importance is the need to bridge the gap, which is the disconnect between policy pronouncements and operational coherence. Coordination among the various AU bodies tasked with countering TOC continues to suffer from resource constraints and insufficient horizontal integration.

In terms of policy, some of the notable instruments include the November 2006 Ouagadougou Action Plan to Combat Trafficking on Human Beings, especially Women and Children, the 2014 Niamey Convention on Cross-Border Cooperation, the August 2019 AU Plan of Action on Drug Control and Crime Prevention 2019-2023 and the December 2018 Enhancing Africa’s Response to Transnational Organised Crimes Project. Institutionally, AFRIPOL is one of the recent institutional structures instituted at the AU as the continent’s law enforcement coordination mechanism to, among others, deal with TOC. An example of the contribution of AFRIPOL in this respect is the launch of ‘Operation TAPI’ in Benin, the first cross-border initiative that targeted a range of illicit activities, including the trafficking of drugs, pharmaceuticals, arms, counterfeit or smuggled goods and environmental crimes. The operation will engage six AU member states: Benin, Cameroon, the Central African Republic (CAR), Nigeria, Chad, and Togo. It is also worth giving due consideration to deepen the role of the Nouakchott Process and the Djibouti Process in contributing to addressing the scourge of TOC. However, the AU has as yet to find ways of bringing counter TOC to the centre of its conflict prevention, management and resolution processes in view of TOC’s deepening entanglement with conflict dynamics. For example, it is rare that reference is made to the policy instruments cited above in responding to and dealing with specific conflict situations.

Beyond the continental frameworks, there is also the issue of how to mainstream response to and address TOC in international conflict management. In Mali, despite a 2018 mandate to address TOC, the UN’s mission, MINUSMA, focused primarily on terrorist financing rather than tackling the broader political economy that sustains organised crime. A similar pattern was noted in the Central African Republic under MINUSCA. These examples reflect a systemic challenge to treat TOC as a central concern of conflict dynamics. They also illustrate the broader problem of siloed mandates and loosely integrated strategies, an area where there is an increasing need for adaptation by peacekeeping missions.

Against this backdrop, in tomorrow’s meeting, the PSC also faces the challenge of how to push away from fragmented, security-heavy responses to more holistic, coordinated strategies that address the structural drivers of TOC and terrorism and emphasise the need for a multidimensional response that combines intelligence-sharing, targeted enforcement, and community resilience-building. The Council is likely to revisit the importance of early warning systems, localised peacebuilding efforts, institution-building, and socioeconomic development interventions as tools for preventing recruitment into criminal and terrorist networks. The 17th Joint Consultative Meeting between the AU PSC and the UNSC, convened on 6 October 2023, also underscored the necessity of a ‘multidimensional approach to tackle the structural root causes of insecurity’, while advocating for coordinated responses to the interlinked threats of terrorism and TOC in the Sahel. It also highlighted the importance of sustained international engagement. The need for stronger international partnerships is likely to be reiterated, as collaboration with global partners remains crucial for securing predictable and sustainable financing for regional initiatives. The PSC had emphasised the importance of cooperation with institutions such as the UN Counter-Terrorism Executive Directorate (CTED), UNODC, and the Global Counter-Terrorism Forum (GCTF) in previous sessions. The 17th Joint Consultative Meeting with the UNSC reinforced the value of aligning AU-led responses with global strategies like the UN Integrated Strategy for the Sahel while calling for increased, predictable funding for regional initiatives. Tomorrow’s session is expected to echo these calls, pushing for greater international support while ensuring that responses remain context-sensitive and locally owned.

The expected outcome of the session is a communiqué. The Council may express deep concern about the increasing threat of the scourge of transnational organised crime in Africa. It may underscore the need for adopting a multidimensional and multipronged approach that goes beyond security and law enforcement instruments. In this regard, it may call for increased use of livelihood support interventions, the rolling out of legitimate local governance structures and other peacebuilding and development support activities as critical measures to address not just the symptoms but also the underlying factors that make TOC possible. Given the transnational nature of TOC, the PSC may reiterate its call for enhanced cross-border cooperation, leveraging the Niamey Convention and the lessons from AFRIPOL’s Operation TAPI. It may also reiterate the importance of the Nouakchott and Djibouti processes while underscoring the need for ensuring that those processes expand their lens beyond the security and law enforcement domain to integrate peacebuilding with a focus on advancing economic development and building of legitimate local governance structures that facilitate the delivery of social services. The Council may also underscore the need for a whole of AU system approach, emphasising both the need for coordination between AU security institutions such as AFRIPOL and CISSA, and importantly, the role of Post-Conflict Reconstruction and Development (PCRD), African Development Bank, AUDA/NEPAD, African Governance Architecture. The PSC may emphasise the need to develop counter TOC as a key area of joint action with the Regional Economic Communities/Mechanisms (RECs/RMs). It may task the AU Commission to develop and present a comprehensive report on both the trends in TOC in Africa and importantly on how the AU contributes to addressing the growing scourge of TOC leveraging on its broader governance, regional integration and peace and security norms and instruments while enhancing the role of AFRIPOL and CISSA in this area. The PSC may also task the AU, working closely with RECs/RMs, to develop guidance on giving growing attention to TOC in developing and implementing peace and security initiatives in conflict prevention, management and resolution efforts. It may also call for greater international support and cooperation in developing responses to the threat posed by TOC.

The Future of United Nations - African Union Peacekeeping Partnership: Practical Considerations for the Berlin Ministerial Conference

The Future of United Nations - African Union Peacekeeping Partnership: Practical Considerations for the Berlin Ministerial Conference

Date | 8 May 2025

INTRODUCTION

This report outlines what could constitute Africa’s key messages to the Berlin Ministerial Conference, informed by the continent’s extensive experience with peacekeeping operations and the imperative to harness the complementarity between UN and African Union (AU) efforts, while also situating the debate on the future of peacekeeping within the broader context of an evolving multilateral system. It then proceeds to highlight specific steps for enhancing the UN-AU partnership, drawing directly from the conclusions of the study on the future of peacekeeping. In its concluding section, the report underscores the relevance of peacekeeping to today’s peace and security challenges while continuing to adapt to remain fit for purpose, as well as its significance as an essential component of the very multilateral architecture that, in spite of its shortcomings, nonetheless offers Africa its most effective platform for advancing its agenda and interests on the global stage.